Henry Bracton (1210-1268) was a jurist who worked hard to codify and update English law, using the well-developed Roman legal system as his guide. His four-volume De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliæ (On the Laws and Customs of England) informed much of English law afterward, even though he didn't finish it (I'll explain why shortly). He had a lot to say about the practice of seeking Sanctuary in a church, about "writs of appeal," and murder fines and dying intestate. But what we are looking at today is the concept of mens rea.

Mens rea, Latin for "guilty mind," was considered by Bracton to be a necessary element of a crime, as opposed to just an actus reus (guilty act). Just as Bracton insisted that stealing required an intent to steal, so the attitude of the law to killing must reflect the agent's intent to kill:

the crime of homicide, be it either accidental or voluntary, does not permit of suffering the same penalty, because on one case the full penalty must be exacted and in the other there should have been mercy. [De Legibus]This was a significant change, and made a harsh law more reasonable. The fact that a felony in modern jurisprudence requires intent starts with Bracton's move away from a strictly "mathematical," eye-for-an-eye approach to punishment.

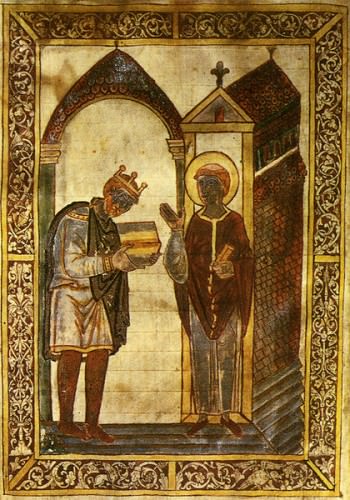

|

| A page from De Legibus |

Whatever the case, he walked away from law and courts for years, becoming a rector in a couple places, then an archdeacon, and finally the chancellor of Exeter Cathedral, in the nave of which he is buried. But in the last year of his life he was drawn into one more court case which, depending upon his reasons for leaving the law just before the second great conflict between a king of England and the Barons, might have been awkward for him. At the end of yesterday's post, the Dictum of Kenilworth was mentioned, allowing the rebels to make a case to reclaim their estates from their king. Henry Bracton was appointed to the committee that heard their cases and decided the outcome, giving him one last chance to practice law—on behalf of people who had been his colleagues on the King's Court.