“You swear that the books received by you shall be safely kept, exhibited and sold in good faith. You swear that you will not deny them nor conceal them, but that you will expose them at proper time and place. You swear that if you are consulted on the selling price of one or more books, you will give in good faith, reserving your proper commission, an estimation, i. e. , such a sum as you would voluntarily give on occasion. You swear that the price of the copy, and the name of the vendor (the person sworn), if required, shall be placed in some part of the book exposed for sale.”[link]

08 April 2023

Medieval Bookshops

07 April 2023

John de Garlandia

Specifically, it describes a practice already in use, known as modal rhythm, which used the rhythmic modes. In this system, notes on the page are assigned to groups of long and short values based on their context. De mensurabili musica describes six rhythmic modes, corresponding to poetic feet: long-short (trochee), short-long (iamb), long-short-short (dactyl), short-short-long (anapest), long-long (spondee), and short-short (pyrrhic). Notation had not yet evolved to the point where the appearance of each note gave its duration; that had still to be understood from the position of a note in a phrase, which of the six rhythmic modes was being employed, and a number of other factors.Modal rhythm is the defining rhythmic characteristic of the music of the Notre Dame school, giving it an utterly distinct sound, one which was to prevail throughout the thirteenth century.[New World Encyclopedia]

Did a bookshop opener write this work? Evidence suggests that it was written in 1240, before John was born (he lived until 1320, so writing in 1240 was not possible), but his name is attached to it, leading to the assumption that he edited the work, or at least wrote later chapters of it. Some of the records of the time refer to John as magister, however, suggesting that he was a teacher at the University of Paris and not just a seller of books. How much he had to do with this work is unknown, but the connection made to it historically is accepted in the absence of other evidence.

For more on the history of musical notation, see here and here.

For information on bookshops in the Middle Ages, well, you'll just have to come back tomorrow.

04 April 2023

The Demon Titivillus

At a time when fear of demons was common, they were "seen" everywhere: causing children to be ill, folk to go mad, cows to dry up, crops to fail, wells to go bad, etc.—they were constantly interfering with human life. One of them was considered the "patron demon of scribes" because he was blamed for errors in manuscripts. His name was Titivillus, sometimes Tutivillus, but in some of the earliest manuscript mentions, their middle letter is unclear and could be n or u/v, so it is written sometimes as Titinillus.

Despite the connection to Caesarius, and a reference in the writings of John of Wales, who died c.1285, as a demon who existed to introduce errors into scribal work, the Oxford English Dictionary's entry attributes the first reference to Peter Paludanus (c.1275 - 1342), who became Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem. The OED suggests the name of the demon might come from Latin titivillitium, a "mere trifle." Titivillus must have been looking over James Murray's shoulder, because Titivillus is clearly found in John of Wales' work long before Peter Paludanus would have been writing. In the Tractatus de Penitentia ("Tract on Sin"), we find

Fragmina verborum titivillus colligit horum

Quibus die mille vicibus se sarcinat ille.

Titivillus gathers up the fragments of these words

with which he fills his sack a thousand times a day.

He gets mentioned in a lot of medieval sermons as a reminder to be ever on guard against error and sloth. Titivillus became a character in medieval Mystery Plays. In the 15th century morality play Mankind, Titivillus is summoned by Mischief and other distractions to make Mankind's life difficult, but only after the audience is asked to pay extra money to make him appear (presumably his costume was suitably fabulous to charge extra). Titivillus' standing as a literary figure fades after that, and Shakespeare uses "Tilly-vally" a couple times when a character brushes off a complaint worthy of Titivillus' sack.

Concerning the phrase "fills his sack." This is not about inducing errors into manuscripts, but something else. Titivillus' career gets conflated with that of other popular medieval figures to watch out for: a "recording demon" and a "sack demon." That's an entirely different post.

Titivillus' presence can still be detected, such as in the fact that the OED (and I cannot believe I have never mentioned it and its mentor James Murray before) misses the earliest reference (but then, I am reading from the first edition; it has been updated). He influences my own work: although I proofread my post hours after writing it and being away, I still miss errors, which are found and shared by a very good friend; I know he is a good friend because he reads daily! (Come to think of it, that friend's name is Nick, and isn't "Old Nick" a name for the devil? Maybe he's trying to undo Titivillus' history of work?)

Well, more demons tomorrow.

20 March 2023

York Library

The collection of works there is estimated to be about 100 items—a remarkable number for the time. A poem by Alcuin mentions 40 different titles, including not only works by Bede and the Church Fathers but also by such classical authors as Aristotle, Cicero, and Pliny.

Alcuin's extant letters tell us that he made trips to procure books for the library, and that he brought some with him when he left York to take up his position at Charlemagne's court at Aachen. Despite his new patron's desire to promote learning, however, Alcuin makes clear that he never created a better library than the one in York.

Some of the books were given to Liudger the Frisian, called the "Apostle of Saxony," when he left studying at York to preach on the continent. Liudger founded a monastery at Werden. The monastery is gone, and some buildings are being used by a school, but it is possible that some fragments of York books still exist in southern Germany.

The Alcuin-era library is no more. Danes sacked the area in 866, and it suffered further at the Harrowing of the North by William the Conqueror.

The York Minster library was formally re-founded when John Neuton (c.1350 - 1414), a canon at York, left a bequest of about 70 books to the Minster. (The illustration above is an initial page of a law text that had been part of his collection.) Few of those original books survive, but York Minster has had a library for over 600 years, thanks to Neuton.

Next I'd like to talk about the Minster itself, and why it's called that instead of Cathedral. Stay tuned.

04 November 2022

Psalter of St. Louis

He appointed a scholar, Honorius of Kent, as Archdeacon of Richmond. Honorius later wrote a book on canon law that was popular enough that it still exists in seven manuscripts.

He seems to have been a patron of the creator of the Leiden St. Louis Psalter. A psalter is a book of psalms, usually lavishly illustrated and made for a wealthy patron. This psalter was made in Northern England in the 1190s, it is 185 pages about 9.5x7 inches. (The picture of it above is from this site where you can purchase facsimiles of medieval works.) It includes 78 illustrations from the Old Testament, psalms, and a calendar of feast days.

There are two versions. The original made for Geoffrey seems to have became the property of Blanche of Castile after his death. This is the Leiden St. Louis Psalter because it ultimately wound up in the Leiden University Library. A new version was made after the death of Blanche for the benefit of her son, Louis IX of France. It is called the Psalter of St. Louis, and resides in the Bibliotheque national de France. You can view the manuscript yourself page-by-page here.

Geoffrey's psalter was used by Blanche to teach the young Louis to read, according to a note in French added to it. We cannot gauge its influence on the young prince, but Louis IX of France is the only French king who became a saint, and maybe we should look at why tomorrow.

22 October 2022

The Talbot Shrewsbury Book

The book is real. It is known as the Talbot Shrewsbury Book (also known as British Royal Library 15 E vi). It is a beautifully illustrated collection of 15 legends, stories, and other information written by several authors. Talbot commissioned it for Henry and Margaret's wedding in 1445. The book includes the illustration of Talbot presenting it to Margaret

Made of parchment bound in 440 pages, it is an example of Medieval/Renaissance book production at its height. The contents start out looking appropriate as a wedding gift for a queen, but near the end they become something else.

The Romance of Alexander the Great is followed by five tales of Charlemagne. After that are two Anglo-Norman prose romances, the story of King Horn and the Romance of Guy of Warwick (one of the most popular medieval romances). There follows a highly creative history of the Crusades.

The last 140+ pages seem to be less oriented toward a queen and more toward a queen's son, leading some to think it was intended for a future son of Margaret and Henry. There is a scholarly dialogue on war and battle, then a Mirror for Princes, a history of Normandy from the 8th century to 1217, a poem about chivalry, and the rules for the Order of the Garter.

If you look closely at the picture, you'll see a little white dog behind the kneeling Earl of Shrewsbury. This is the Talbot Dog, and it has its own place in history, which I'll talk about next.

15 September 2022

The Venerable Bede

Bede (Beda, Bæda) was born about 672-3 o lands belonging to the monasteries of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow in Northumbria (now Wearside and Tyneside). Because the name Beda appears on a list of kings of Lindsey in Northumbria, and because of Bede's obvious connections to notable men, we think he came from a well-to-do family, possibly royal.

He was sent to the monastery at Monkwearmouth at the age of seven as a puer oblatus ("a boy oblate" or "boy dedicated to God's service"). At the time, the abbot was Benedict Biscop. Some years later he went to Jarrow, which was dedicated on 23 April 635. A plague in 686 left only two survivors at Jarrow who knew the holy services, Abbot Ceolfrith and a young boy. Bede would have been about 14 and was likely that boy.

Bede was ordained a deacon earlier than the typical age of 25, indicating exceptional ability and respect earned. He became a priest at the age of 30. In started writing about 701, with De Arte Metrica ("On Metrical Art" [meaning poetry]) and De Schematibus et Tropis ("On Figures and Tropes"). Once started, he did not stop writing, producing works and translations to explain history, the church, church services and religious trappings, the Bible, histories of saints, histories of abbots of Jarrow, and far more.

One of his works created a stir: in De Temporibus ("On the Times," meaning the ages of the world), he calculated that Christ was born 3,952 years after Creation. The generally accepted feeling was Isidore of Seville's opinion that the length of time was more than 5,000 years. Some monks complained to Bishop Wilfrid of Hexham (mentioned here). Wilfrid did not share their concern about Bede, but a monk who was present relayed the event to Bede, who wrote back explaining his calculations and asked the monk to share his thinking with Wilfrid. Regarding dates: the use of Anno Domini ("Year of the Lord") to count years since the birth of Christ was introduced by Bede. Bede also writes extensively on the controversy over the proper dating of Easter Sunday.

We know from a letter written by a disciple of his, Cuthbert (not St. Cuthbert) that he began to feel ill, his breathing became labored, his feet began to swell. He asked for a box of his things to be brought to him, and gave away his possessions, described as "some pepper, and napkins, and some incense." He died 26 May 735, his body being found on the floor of his cell that morning.

In 1899, Pope Leo XIII named him a "Doctor of the Church," the only native Englishman to be given that title.

Although Bede's literary output and life have countless points from which I could find a link to tomorrow's blog post, I wanted to talk about the pracrive=ce of handing a seven-year-old over to be raised by strangers in a monastery. Next time.

11 September 2022

The Life of Asser

John Asser was a Welsh monk at St. David's in Dyfed (southwest Wales). We know little about him until he was recruited by Alfred to join his court for his scholarly abilities.

In the biography, we learn that Alfred decided on St. Martin's Day in 887 (November 11) that he wanted to learn Latin, and asked Asser to be his teacher. Asser asked for six months to consider, since he did not want to leave his position at St. David's. This was granted, but Asser fell ill when he returned to St. David's, and a year later Alfred to ask why the delay. Asser said he would decide when he recovered. The monks at St. David's felt the arrangement could be beneficial to them, and Asser agreed to divide his time between the two obligations.

Asser mentions reading to Alfred in the evenings, meeting Alfred's mother-in-law, and traveling with him. He describes the geography of his travels in England, as if he were writing for an audience unfamiliar with the English countryside: possible for his Welsh countrymen, whose he wished to educate about the king. He also includes some anecdotes that help flesh out information otherwise found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The biography does not mention any events after 893, although Alfred lived another six years (and Asser well beyond that). That fact, and the fact that there is a single manuscript, suggests that what we have is merely an early draft that never was finished and sent to be copied and distributed. On the other hand, there are other literary works that show evidence of access to Asser's manuscript. A history written by Byrhtferth of Ramsey in the late 10th century quotes large sections of Asser. An anonymous monk in Flanders seems acquainted with Asser's work in his 1040s-written Encomium Emma (Latin: "Praise of [Queen] Emma"). In the early 12th century, Florence of Worcester quotes Asser in his chronicle. It seems clear that Asser's manuscript either "made the rounds" or lived in a much-visited library; we just don't know where it was in its earliest existence.

We do know that Bishop Matthew Parker (died 1575) possessed it in his library, but it was not included in the catalog when he bequeathed his library to Corpus Christi, Cambridge. Prior to that, it was owned by the antiquary John Leland in the 1540s. He might have acquired it when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries, salvaging it when their properties and possessions were being sold off.

I seem to have turned a life of Asser into a discussion of his one known piece off writing.

As a reward, and possibly to keep Asser from going back to Wales, Alfred gave him the monastery of Exeter. He was made Bishop of Sherborne sometime between 892 and 900. He may have been a bishop already, at St. David's.

In 1603, the antiquarian William Camden printed an edition of Asser's Life in which he ascribes to Asser the founding of a college at Oxford. This extraordinary and evidence-free claim was repeated, but no modern scholar or historian.

The Annals of Wales (probably kept at St. David's) mention Asser's death in 908. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 909 (or 910, in some versions; different chroniclers started the year at different dates) tells us "Asser, who was bishop at Sherborne, departed."

And now for something completely different: one of the anecdotes he tells is about a daughter of King Offa, who married a king of Wessex and became a stereotype of Disney films: an evil queen. Tomorrow I'll tell you about Eadburh.

03 September 2022

The Ottonian Renaissance

Part of this was not so much a rebirth as an influx of culture from the east: the Byzantine Empire maintained some of what Western Europe "lost" during those centuries. When Otto I married his son, Otto II, to Theophanu, the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimiskes, he opened the door to Byzantine art and increased commerce. Another important figure involved was Gerbert of Aurillac, who became Pope Sylvester II during the reign of Otto III.

Sylvester II introduced the abacus for computation, and wooden terrestrial spheres for the study of the movement of planets and constellations. He composed De rationalis et ratione uti (Of the rational and the use of reason) and dedicated it to Otto III. Promoting reason over faith was an important step in the study of the sciences. Sylvester also promoted the expansion of abbey libraries, particularly at Bobbio Abbey (where St. Columbanus wound up earlier), which had almost 600 works.

Arts and architecture also stand out in an examination of the Ottonian Renaissance. The revival of the Holy Roman Empire brought inspiration to think on a grander scale and create art and buildings that reflected the grandeur to which the Ottonians believed they were heir. Large bronze doors on churches and gilded crosses became more common. Ottonian patronage of monasteries produced grand illuminated manuscripts. One of the most famous scriptoria was Reichenau, which produced Hermann of Reichenau. This is also the period of the literary output of Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim.

A campaign of renovating churches and cathedrals also took place. (The illustration is an ivory plaque showing Otto I on the left, shown smaller than the saints, presenting Magdeburg Cathedral to Christ.) Longer naves and apses were inspired by Roman/Byzantine basilica. Many of these church designs and re-designs came form the hand of Otto I's brother, Bruno the Great. Bruno extended the cathedral in Cologne to rival the size of St. Peter's in Rome (Cologne Cathedral burned down in 1248, alas). He also built a church dedicated to St. Martin of Tours.

Ivory carving and cloisonné enamels were also widely produced in this era. A major workshop for cloisonné enamels was established by Archbishop Egbert of Trier, using a Byzantine technique of "sunken" enamel, where thin gold wire was soldered to a base, and colored glass melted into the spaces, as opposed to the original style of affixing gemstones as an inlay.

I find Ottonian art, though lovely, does not tickle my interest as much as those "wooden terrestrial spheres" of Pope Sylvester, so I'm going to look into those for next time.

27 August 2022

Medieval Paints and Pigments

Where did medieval manuscript illuminators get their colors?

Well, first thing to realize is that they weren't re-inventing the wheel: Romans had colored paints available to them. The Romans used the term minium to refer to pigment from ground cinnabar (brick-red mercury sulfide) or red lead (lead oxide). Some minerals that were dug up and ground included:red ochre — iron oxide/hematite (rust color)

yellow ochre — silica and clay/iron oxyhydroxides (shades from cream to brown)

umber — iron and manganese oxides (from cream to brown)

lime white — dried lime/chalk (white)

green earth (Verona green) — celadonite/glauconite (green)

azurite — carbonate of copper (blue)

ultramarine — lapis lazuli (blue)

Pigments could also be made from plants. Red could be made from the root of the Eurasian madder plant. The Crozophora plant's seeds produced a violet-blue. Saffron gave yellow. Woad and indigo came from plants that carried the same name. Let's not forget insects, that could be crushed to give the bright-red carmine (from the cochineal or Dactylopius coccus scale insect).

Preparation of paints was a careful process. The coloring was usually mixed gum arabic or with egg. Egg tempera (from the yolk) or egg glair (from the white) were ways to "fix" the pigment to the surface you were using. Because the egg tempera could crack, it was applied in paintings in thin layers.

Some colors were more special than others. Ultramarine (literally "beyond the sea"), the blue made from grinding lapis lazuli, came from Afghanistan and was very expensive to obtain. This brightest blue, however, was associated with the gown of Mary, the mother of Jesus, so it was greatly desired and worth the price.

Another questio0n regarding color in the Middle Ages comes to mind, however. How did they get the color into glass? That's for next time.

26 August 2022

Masters of Marginalia

Today we look at the less serious additions made by monks who were no doubt bored and decided to exercise their sense of humor.

There are so many web pages where you can find more in varying stages of frivolity and obscenity if you simply search "medieval marginalia" the you can send days of diversion that it would be pointless for me to try to give you more than just a bare minimum of representative figures.

These marginalia don't make much sense, in that they don't generally have anything to do with the text they accompany except in the most tenuous way. For instance, the bottom illustration in the collection I have included shows a fox as a bishop preaching to a flock of different birds, which would normally be his prey. Commentary by a monk on what he really thinks about bishops and their attitude toward their congregations? Or just an attempt at an ironic drawing of animals?

Snails actually show up frequently, often involving combat. The top right shows a snail with an animal's head. Below that is a snail fighting a knight. There is conjecture that the shell of the snail, since it resembled a kind of armor, was an appropriate foe for a knight.

Some additions are attractive additions, like the unicorn, although right above it is a curious animal-headed set of tentacles or vines. I would call that simply a doodle.

Then you have pictures that are far more irreverent than a fox preaching to birds, such as the monk sniffing the butt of an ... animal? Demon? Hard to say what it is in that top-left illustration. At least it is very attractively enclosed in the curves and points of its surrounding frame.

We should note that the making of marginalia was not that impulsive; that is, the manuscript copyist did not say to himself "I'll just out a goose playing a lute here." These were added by someone who was sitting with access to multiple colors of ink in front of him. He was the monk tasked with "prettying up" the manuscript in order to make it more valuable and less likely to bore the reader. Hundreds of years later, these colors remain on the vellum, which has got me thinking: where did colored inks/paints come from in the Middle Ages?

I will look into that question, and get back to you. See you tomorrow.

25 August 2022

The Scholiasts

Marginalia are marks or notations or illustrations drawn into (obviously) the margin of a document. They have another name: apostils, from the Middle French verb apostiller, meaning "to add marginal notes." This in turn was from Latin postilla, "little post." The origin of postilla might be (we aren't sure) the Latin phrase post illa, which would mean (if Latin used it this way) "after these things."

Scholarly works and the Bible would have marginalia such as numbers to denote divisions of texts, or notes for liturgical use. There may even be scholia, ("comment, interpretation") which are corrections in grammar or translation or comments on the text referencing other works. Errors could creep into the arduous task of copying, and a subsequent copier of the copy could be aware that a mistake had been made, which he would seek to correct with a scholia. The person who added scholia was a scholiast, a word that goes back to the 1st century CE.Additionally, a monk who had knowledge of a commentary on a document he was copying might decide to add scholia to offer an explanation on the particular passage in front of him. Modern book lovers debate over the propriety of writing in a book; these monks saw fit to "pre-write" into the work for clarification.

This is not to say that all scholia are to be trusted. Mistakes can be made. For example, there is a 1314 manuscript of a 3rd century text, Porphyry’s Homeric Questions (a discussion of problems that arise from reading the works of Homer). There are other manuscript copies of the works of Homer that have scholia that are clearly quoting Porphyry—and they are different. The person adding the scholia has mis-remembered the original; or did he? Maybe the person who made the 1314 copy was being sloppy while looking back and forth from the written to the being-written in front of him.

If I am in the position where I cannot digitally copy and paste, and must read + remember + type a longish passage, I must be extra careful because I know how easily my short-term memory can "smooth over" the original. I cannot imagine a monk would not try to speed up the tedious process of copying by spending less time shifting back and forth.

In the illustration above, a printed copy of Homer's Odyssey (printed in 1535), the printer Johann Herwagen (1497–1559?) has simply included (the narrower column) and additional scholia from other manuscripts, leaving the reader to decide which is preferred.

If the readers of this blog follow any other information about the Middle Ages, however, yesterday's reference to marginalia conjured images of, well, images. The phrase medieval marginalia usually makes people think of pictures, and I'll give you a representative sample of those next time.

24 August 2022

The Writing Room

The scriptorium or "writing place" was a standard part of a monastery's architecture, and an early non-agricultural example of an "assembly line." Some monks had an excellent hand for lettering, some were good at illustration. Of course, even before anything could happen in the scriptorium, someone had to make parchment and ink (see the links).

Cassiodorus considered scriptorium work so vital that he established careful training for scribes, and exempted the top performers from daily prayers and allocated extra candles so they could spend more hours copying texts. A scribe therefore might work from six hours per day up to twice that or more for the best ones.

Even good scribes, however, were not always happy in their work. The scriptorium was placed in the complex to be distraction-free. Imagine working long hours in a silent room, bent over, eyes close to the page, no "coffee breaks" unless it were for prayers, the pressure to copy texts exactly. The need for decent lighting meant having windows that were open to the cold air all winter; gloves would have interfered with the fine penmanship needed. Monks were stressed, and often gave themselves breaks by inappropriate notes sketches in margins. One manuscript ends with the personal observation “Now I’ve written the whole thing. For Christ’s sake, give me a drink.” (You can read all about it in here, page 40.)

The illustration above is likely not a good depiction of the actual environment. The light from the windows needs to be on the page, not in the monks' eyes. A better layout is seen in the Plan of St. Gall, which I wrote about here. It is a manuscript that shows the layout of the Abbey of St. Gall, and the scriptorium is clearly a room with desks around the edges and a worktable in the center. You can see it on the left side of the illustration to the right of this paragraph.If you like the term "Dark Ages" and think there was no education for centuries in Europe, we must agree to disagree, but I will say that monasteries helped preserve culture and learning. They were not just copying the Bible and works by Christian authors like Augustine: Aristotle and others from the Classical Era were being preserved and shared, and the act of copying also educated the monk who was doing the reading. Abbot Trithemius (1462 - 1516) wrote

As he is copying the approved texts he is gradually initiated into the divine mysteries and miraculously enlightened. Every word we write is imprinted more forcefully on our minds since we have to take our time while writing and reading. (In Praise of Scribes)

All seriousness aside, however, much can be made of the frivolous illustrations tucked into and around the lines of text. They are definitely worth looking at next time.

23 August 2022

Copyright–A Brief History

The reference to copyright that has been made in the last few posts is over the Cathach, the psalter (supposedly) copied by St. Columba from the scriptorium of Abbot Finnian of Movilla in the 6th century. Finnian objected to Columba having it and, when appealed to over the conflict, the High King of Ireland Diarmait said "To every cow belongs her calf, therefore to every book belongs its copy." Whether this was the actual cause of the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne is not firmly established.

Between those two dates were other attempts at protecting the written word. Aldus Manutius (1449 - 1515), who invented the paperback and italic writing, received a privilegio from the Doge of Venice in 1502 forbidding the use or imitation by others of his italic font. Earlier in Venice, Marc' Antonio Sabellico in 1486 was given from the Venetian cabinet the sole right to publish his work on the history of the Republic; the fine was 500 ducats.

There seems to have been a "right to image" in Classical Rome for death masks and statues of one's ancestors, but the "copyright holder" was the family of the person pictured, not the artist.

Medieval writers (such as Chaucer) were less likely to write something new than they were to take a familiar story (like the Trojan War) and put their own spin on it. Even Shakespeare was getting his plots from history and literature. This seems to be the opposite of why the Statute of Anne was made (see its full title). Encouraging authors to create more by protecting the originality of their work was not something on the mind of the medieval author.

It seems to me that a strong sense of copyright in Ireland of the 6th century, as suggested by the Cathach anecdote (whose link to the Battle was made long after the event and is not corroborated by any contemporary documents) would have led to more examples of evolution of actual law over time. Columba's desire to have a copy of a manuscript was not that unusual. One of a monastery's typical functions was to copy manuscripts for preservation and dissemination, and we'll talk more about that next time.

22 August 2022

The Cathach

There is a legend that it was made in one night, copied from an original in Movilla Abbey. Supposedly, Abbot Finnian of Movilla objected to Columba making and taking a copy, and the conflict led to a terrible battle. during which 3000 men were killed. This is sometimes referred to as the first war over copyright.

This is unlikely; it is, however, associated with battle for another reason. The O'Donnell clan possessed it, and as a holy book it was considered to give protection in times of battle. Safe in its cumdach (a reliquary specifically made for a book, pictured above), it was carried by a holy man or monk three times around the waiting army prior to battle, and a rallying cry of "An Cathach!" ("The Battler!") would go up from the troops.

The cumdach was made for it. It consists of a wooden box that has been re-decorated a few times. It has bronze and gilt-silver plates, and settings for glass and crystal "gems." Completed in Kells in the second half of the 11th century, it was added to in the late 1300s with a Crucifixion scene, and then again in the 16th and 18th centuries. The cumdach is in the National Museum of Ireland. The Cathach itself is preserved and studied in the Royal Irish Academy.

What was the likelihood that a battle would be fought over copyright? Hard to say, especially since copyright as we think of it in modern times is a fairly new idea. Or is it? Let's talk about that next time.

21 August 2022

Battle of Cúl Dreimhne

The Cathach is a psalter, a collection of the Psalms from the Bible. The original was at Movilla Abbey, in the possession of Saint Finnian of Movilla. A visiting Columba made a copy of it miraculously in a single night, in order to have his own, but Finnian objected to this.

The question arose: was the copy owned by Finnian because he possessed the original, or by Columba because he made it? The High King of Ireland, King Diarmait Mac Cerbaill, famously proclaimed "To every cow belongs her calf, therefore to every book belongs its copy." Then (according to this version of the story), Columba raised an army to fight for his right to keep the copy. It is far likelier that the battle was a dynastic conflict because of the way Diarmait had assumed the kingship after his predecessor's death.

Another theory for the start of the battle is the violation of the rules of sanctuary when a man under Columba's protection was forcibly taken and executed, whereupon Columba raised an army against Diarmait. Columba was exiled for his actions and required to create as many souls for Christ as had been killed in the battle (3000). There is no evidence that his missionary work after that time was the result of exile rather than a desire to spread Christianity.

But as to the battle itself: it was in northwest Ireland in what is now County Sligo. You can visit the site of the "Cooldrumman Battlefield" at the foot of Ben Bulben. Modern scholars point out that the earliest references to the battle do not mention a book at all.

Was the Cathach so important that a battle could arise over it losing its uniqueness and its place on Movilla Abbey. To answer that, we need to take a closer look at the Cathach itself, and that's what we'll do next.

19 August 2022

St. Columba

"Columba" was not his given name, about which there is some debate. For the first five years of his life he lived in the village of Glencolmcille. The Abbot of Iona, Adomnán, who wrote a biography of Columba, believed Colmcille was his given name, and the village was later named after him. Other sources state that his given name was Crimthann ("fox"). "Colmcille" is Irish for dove; when writing about him in Latin, "Columba" is chosen because it also means dove.

He studied at a few different places before winding up, in his twenties, at Clonard under Finnian, where he became a monk and was eventually ordained a priest. Returning to Ulster years later, Columba became known for his powerful speaking voice. He founded several monasteries. He also planned a pilgrimage to Rome, but only got as far as Tours, whence he brought back a copy of the Gospels that had supposedly rested on the bosom of St. Martin for a century.

Columba's interest in holy literature turned into a controversy. He made a copy of manuscript in the scriptorium of Movilla Abbey, a place he had studied before his time at Clonard. The head of the Abbey, Finnian of Movilla, disputed his right to keep the copy he had made. Anecdotally, this led to a battle, the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne.

Another controversy in which he became embroiled concerned the concept of sanctuary. Prince Curnan of Connacht was a relative of Columba. When Curnan accidentally killed a rival in a hurling match, he sought sanctuary in the presence of his ordained relative, Columba. King Diarmait of Cooldrevny's men forcibly dragged Curnan away from Columba and killed him. Columba decided he should leave Ireland.

Columba went to Scotland in 563 with twelve companions where he started preaching to the Picts. For his founding of one of the most important centers of Christianity in Western Europe, and his conflict at Loch Ness, come back tomorrow.

15 August 2022

The Eddas and Tolkien

There was Motsognir | the mightiest made

Of all the dwarfs, | and Durin next;

Many a likeness | of men they made,

The dwarfs in the earth, | as Durin said.

11. Nyi and Nithi, | Northri and Suthri,

Austri and Vestri, | Althjof, Dvalin,

Nar and Nain, | Niping, Dain,

Bifur, Bofur, | Bombur, Nori,

An and Onar, | Óin, Mjothvitnir.

12. Vigg and Gandalf | Vindalf, Thorin,

Thror and Thrain | Thekk, Lit and Vit,

Nyr and Nyrath,-- | now have I told--

Regin and Rathsvith-- | the list aright.13. Fili, Kili, | Fundin, Nali15. There were Draupnir | and Dolgthrasir,

Hor, Haugspori, | Hlevang, Gloin,

Dori, Ori, | Duf, Andvari,

Skirfir, Virfir, | Skafith, Ai.

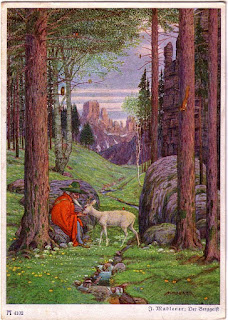

You can see here the source of familiar dwarf names in his stories, and one extra: Gandalf (appropriately tinted gray). The name is interpreted as "wand elf" and seems to denote either a magical dwarf or a dwarf with a staff. Speaking of Gandalf the Grey, the illustration above is a postcard in Tolkien's possession which he said was the inspiration for the character of Gandalf. It is called Der Beggeist ("The Mountain-spirit"), and was painted by a German artist in the 1920s. The character's colors are off for Gandalf, and his obvious connection to nature suggests rather Gandalf's colleague Rhadagast the Brown, but something about it caused Tolkien to label it "Origin of Gandalf."

Now, to get from a 20th-century scholar back to medieval scholarship: Tolkien wrote poems, one of which, Fastitocalon, referenced a giant mythological sea creature. This was from an Old English poem called "The Whale," and it's worth taking a look at next time.

27 July 2022

William and the Werewolf

Such was the case of the story of Guillaume de Palerme, or "William of Palerme" which was later re-titled in English "William and the Werewolf." This story gives us in early English the first instance of the pronoun "they" being used to refer to singular subject in the sole English manuscript dated to 1375, but the original French version was probably composed about 1200. The story was commissioned by Yolande, daughter of the Count of Hainaut, Baldwin IV (once mentioned here). The French version also exists in a single surviving manuscript from the 1200s.

The main character, William, is the son and heir to the King and Queen of Palermo, and his birth is welcomed by everyone except his uncle, who stood to inherit if the King had no heirs. The uncle plots to poison the child. Shortly before he can do so, a wold leaps the wall of the royal gardens, snatches the babe in its mouth, and flees. His parents mourn the loss, after a search fails to find the wolf.

Flashback! The author then tells us whence came the wolf. An evil queen in Spain, desiring to have her children by the king inherit rather than the king's eldest son by his first wife, transforms Prince Alfonse into a wolf. Alfonse, however retains his human understanding, In his wandering, the wolf Alfonse overhears the plot to poison the prince and decides to save the child. He teals him away and deposits him with a cowherd, who raises him.

Years later, the Emperor of Rome goes hunting in the wood and comes upon a young man with such regal bearing and handsome features that he insists on taking him away to raise him "properly." There, William and the emperor's daughter, Melior, fall (inappropriately) for each other. Their secret love is aided and abetted by Melior's friend Alexandra.

The emperor of Greece wants to marry his son to Melior, and her father agrees. The young lovers decide to flee, and Alexandra helps them by procuring two white bear skins, sewing the two into the skins (except the hands, so they can eat), and they flee. They are not really suited to surviving in the wild, but Alfonse the wolf reappears, bringing them fancy food and killing two deer so the pair can have nicer skins to live in and hide out as deer instead of white bears.

There's more, much more. You can read a modern English translation here if you like. Tomorrow? More about werewolves, the cool medieval kind, not the modern hour kind.

19 June 2022

Guibert of Nogent

Born c.1055 to minor nobility, his was a breech birth. His family made an offering to the Virgin Mary the he would be dedicated to a religious life if he survived. Guibert's father (according to his autobiography) was violent man who died while Guibert was still young. Guibert believed his father would have broken the vow and would have tried to get Guibert to become a knight.

At the age of 12, after six years of a strict tutor for the boy, his mother retired to an abbey near saint-Germer-de-Fly. Soon after, Guibert entered the Order of Saint-Germer, studying classical works. The influence of Anselm of Bec inspired him to change his focus to theology.

The first major literary work of his was the Dei gesta per Francos ("God's deeds through the Franks"). It is a more polished version of the anonymous Gesta Francorum. His additions give us more information about the reaction to the Crusade in France.

His autobiography is also patterned after another work, the Confessions of St. Augustine. It is a lengthy work dealing with his youth and upbringing and his life in a monastery. There are references that give us insight into daily life, such as when he denigrates someone for their manner of dress:

But because there are no good things, that do not at times give occasion to some wickedness, when he was one day in a village engaged on some business or other, behold there stood before him a man in a scarlet cloak and silken hose that had the soles cut away in a damnable fashion, with hair effeminately parted in front and sweeping the tops of his shoulders looking more like a lover than a traveller.

Guibert's criticisms tell us something about attitude toward certain fashions.

He had a skeptical view on saints:

I have indeed seen, and blush to relate, how a common boy, nearly related to a certain most renowned abbot, and squire (it was said) to some knight, died in a village hard by Beauvais .on Good Friday, two days before Easter. Then, for the sake of that sacred day whereon he had died, men began to impute a gratuitous sanctity to the dead boy. When this had been rumoured among the country-folk, all agape for something new, then forthwith oblations and waxen tapers were brought to his tomb by the villagers of all that country round. What need of more words? A monument was built over him, the pot was hedged in with a stone building, and from the very confines of Brittany there came great companies of country-folk, though without admixture of the higher sort. That most wise abbot with his religious monks, seeing this, and being enticed by the multitude of gifts that were brought, suffered the fabrication of false miracles. [Treatise on Relics]

...and on saints' relics:

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, eagerly desired the body of St Exuperius, his predecessor, who was honoured with special worship in the town of Corbeil. He paid, therefore, the sum of one hundred pounds to the sacristan of the church which possessed these relics that he might take them for himself. But the sacristan cunningly dug up the bones of a peasant named Exuperius and brought them to the Bishop. The Bishop, not content with assertion, exacted from him an oath that these bones brought were those of Saint Exuperius. "I swear," replied the man, "that these are the bones of Exuperius: as to his sanctity I cannot swear, since many earn the title of saints are far indeed from holiness." [Treatise on Relics]

He died in 1124.

Speaking of deeds of the Franks, there should be some interesting items to glean from the aforementioned Gesta Francorum. Stay tuned.