...and maybe he defeated the Loch Ness monster.

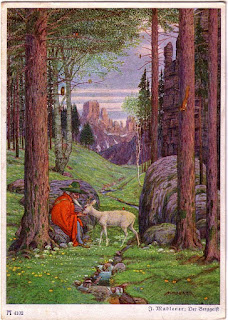

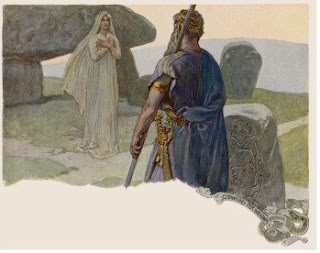

At the northern end of Loch Ness there is an outflow, the River Ness, that flows northward about six miles through Inverness to the sea. In 565, St. Columba was in Scotland, building abbeys such as Iona and converting Picts. He heard that a monster came from the river and killed a Pict. Columba came to the shores of the river and confronted the beast, which attacked one of Columba's companions, a disciple named Lugne. Columba saved Lugne and banished the beast back to the depths. Of course, the monster would return in the 20th century.

The abbey at Iona became the birthplace of Celtic Christianity. Iona is a small island on the west coast of Scotland, and the abbey he built there still stands as a church. A note on the name "Iona." The Life of St. Columba refers to it as "Ioua insula," and it seems likely that a mis-reading of the script called Insular Minuscule enabled readers to mistake the "u" for an "n." No other reference to it in the Middle Ages is similar to the word "Iona" at all.

Columba stayed at Iona until his death on 9 June 597 (also his feast day), and was buried there. The relics of this saint were removed to save them from desecration by marauding raids by vikings in the 9th century. He is considered one of the three patron saints of Ireland, along with Patrick and Brigid of Kildare.

Let's look in more detail about an incident in Columba's life that I've mentioned twice now: the war fought over copyright. See you tomorrow.