Yesterday we discussed the problem of decay when a corpse had to be transported over a long distance. A medieval historian named Boncompagno coined the term

mos Teutonicus ("German custom") to describe how Germans dealt with death of an aristocrat on Crusade.

The ultimate goal was to have a complete skeleton to take home and bury. The first step was to remove the entrails. Internal organs were not going to be preserved, and not considered an important part of the ultimate result, so they would be buried. Often, however, the heart would be carefully saved.

Then the body hd to be "de-fleshed." The most efficient way to do this (with minimal handling of the corpse) was to boil it. As Boncompagno wrote:

The Germans remove the intestines from the corpses of high-ranking men when they die in foreign countries, and let the rest boil in cauldrons until all the meat, tendons and cartilage are separated from the bones. These bones, washed in fragrant wine and sprinkled with spices, are then taken back to their homeland.

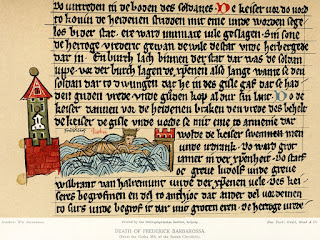

The boiling process would take hours. Now, the likelihood of having a cauldron large enough for the body seems dubious. On the other hand, an enormous retinue of nobles and their households making a long journey would have equipment for feeding a lot of people. It is possible that there were copper tubs for heating water/cooking that could accommodate an adult corpse. In the case of Frederick I Barbarossa who drowned during the Third Crusade in 1190, however, the report is that he was cut up and cooked. In 1167, he had ordered the same for several bishops and princes who were with him during his conquest of Rome and died from dysentery, delivering their bones to their respective homes.

Modern science has taken an interest in this practice: the bones of Emperor Lothar III were said to be the end result of mos Teutonicus after he died crossing the Alps in 1137. Scientific analysis of the breakdown of amino acids suggests that they were boiled for six hours. Modern forensic analysis has likewise taken advantage of remains that were preserved by methods other than putting them in the ground where they could thoroughly decompose. Richard I Lionheart's heart was preserved and sent to Notre Dame. It has been confirmed to 1) be a heart, and 2) have been embalmed with myrtle, daisy, mint, and frankincense, giving clues to medieval embalming preservation techniques.

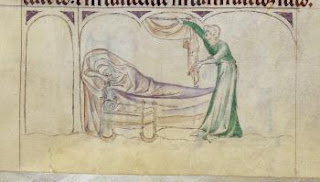

The Church looked down on mos Teutonicus, as did other nations. The French much preferred taking the time and effort to embalm the body. The English were fine with dividing body parts, such as sending the heart to a separate place for sentimental reasons. The Church wanted the entire body intact for resurrection at the final trump. Pope Boniface VIII issued a papal bull in 1299 (re-issued in 1300, in case they weren't listening the first time) condemning the practice of separating the body.

(Later years have ignored this bull. Keeping a memento—sometimes grisly—of a loved one is not uncommon. Napolean's heart was given to Josephine, Chopin's heart was put in a crystal jar, Thomas Hardy's heart—what was left after being cut out and partially eaten by a cat—was to be buried in Stanford, Dorset. Mary Shelley supposedly had Percy Shelley's heart in a box; I say "supposedly" because the lump saved from his cremation could have been anything; the eyewitness who grabbed it, burning his hand in the process, said it was the heart. It's more poetic that way.)

As often happens, I have discovered in relating all the above that I have mentioned Frederick I Barbarossa more than once in the history of this blog without every going into detail about who he was. Tomorrow I will correct that oversight. Until then...