Clement died 20 April 1314. The papal conclave to elect a successor was convened on 1 May and lasted until 7 August 1316 with the election of John XXII. The conclave had such a difficult time electing a pope because of three opposing factions of cardinals: Italian (eight cardinals, who wanted to return to Rome), Gascon (10 cardinals, who enjoyed the convenience of having the papal offices so close to home), and French/Provençal (five cardinals, who did not appreciate a return to Rome or the special privileges enjoyed by the Gascon cardinals under the Aquitainian Clement V).

The Italian cardinals tried and failed to gain the support of the Provençal cardinals. The various groups were refusing to meet until they could get their own politics worked out. King Philip IV of France convened a group of jurists to help find a resolution, but he died on 29 November 1314. His son, Louis X, tried to get the cardinals to come together at Lyons.

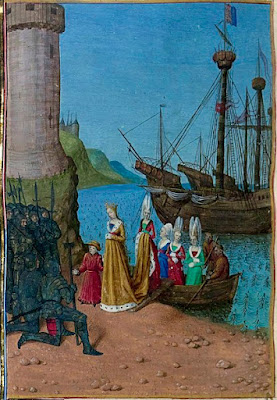

Louis had a special reason to get a pope elected. His wife had been imprisoned for adultery, but automatically became queen consort when Louis succeeded his father to the throne. Louis wanted a wife to rule by his side and bear children, but without a pope, he could not obtain the annulment he needed. Louis died on 5 June 1316, and the papal conclave became the problem of his brother, Philip, who locked the cardinals in a Dominican convent until they made a final decision.

Ultimately, a compromise candidate was chosen: Jacques d'Euse was 72 years old, and his selection seems to have been a way of "kicking the can down the road" so that they could have a pope now, knowing that they would be having this discussion again presently. Jacques d'Euse surprised them all, however, ruling as Pope John XXII from 7 August 1316 until his death on 4 December 1334!

But back to Louis X of France. He never did get an annulment, but his problem was solved another way, and he was able to remarry and produce a son by his new wife, a son who reigned as King of France for five days. For that sad tale, you will have to wait until next time.