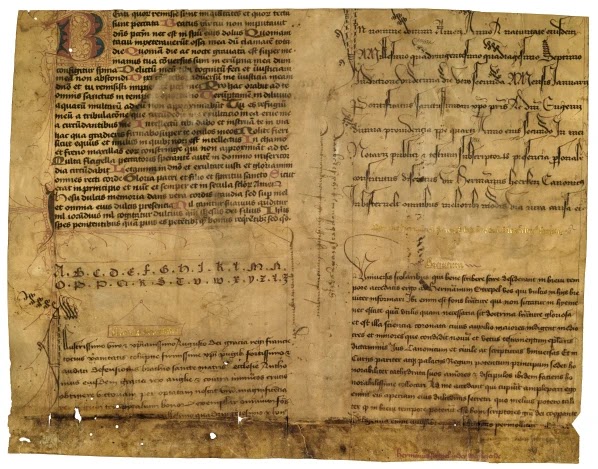

According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland), written by Christians and incorporating Irish mythology, Noah's son Japheth had a descendant who was a Scythian king named Fénius Fairad, who was one of 72 chieftains who built the Tower of Babel. His son wed the daughter of an Egyptian pharaoh. Their son, Goidel Glas, invents the Gaelic language after the confusion in languages caused by Babel.

Goidel's descendants leave Egypt for Scythia, then leave Scythia and wander for 440 years, eventually reaching Iberia/Hispania. One of the settlers, Íth, builds a tower there so tall that he spots the island of Ireland. Íth sails there, meeting three kings/gods of the Tuatha Dé Danann. Íth is killed, his people return to Iberia; then the sons of Íth's brother, Mil, lead an invasion force for revenge.

Landing in Ireland, they meet three queens/goddesses of the Tuatha, one of whom, Ériu, prophecies good fortune for them if they name the Ireland after her (this is where we get the name Eire). The Milesians and the Tuatha meet and agree to a three-day truce, during which the Milesians must take to their ships and wait off shore. The Tuatha create a storm that prevents the ships from landing again, but a Milesian, Amergin, knows a magical verse that calms the storm. The ships return, and the agreement is made with the Tuatha that the Gaels will live above ground, and the Tuatha must live below ground.

Why the link to Iberia/Hispania, Spain? One reason might be the coincidental similarity between the names Iberia/Hiberia and Hibernia, as well as the names Galicia and Gael. Isidore of Seville made many erroneous (but widely believed) concordances based on words and his take on history. Isidore also described Iberia as the "mother[land] of the races" (we don't know why). Historians Orosius and Tacitus thought Ireland was situated between Iberia and Britain, and one modern scholar (read his essay "Did the Irish Come from Spain?" here) sees this as a reason to think that Irish arrivals would have started from Spain.

In truth, DNA analysis shows close relations between modern Irish and northern Iberians. Hmm.

Regarding Isidore of Seville, whose works were considered the encyclopediae of his time and generations after: he has been mentioned, but has never been the subject of a post. I'll fix that tomorrow.