Gerald of Wales (c.1146 - c.1223) provided us with extensive information on

Ireland and Wales and England of his time. Serving several Plantagenet kings, he traveled in their service and wrote about what he saw and was told. Two of his several works were the

Descriptio Cambriae ("Description of Wales") and the

Itinerarium Cambriae ("Itinerary Through Wales"). He claims fairness in his treatment of the subject of his homeland, splitting the

Descriptio into two parts, first the virtues of the Welsh, then their vices.

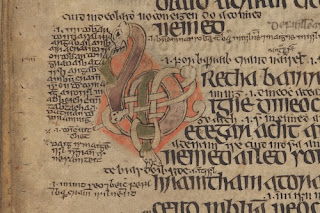

His writing for the Itinerarium through Wales is also better informed than his Topographia of Ireland, since he spent a little time in only a few Irish locations and gathered stories from men he deemed "reliable." He was more familiar with Wales, and he did in fact have an itinerary (see the illustration).

This tour took place while he was accompanying the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1188, preaching to raise a Third Crusade. Gerald writes the Itinerarium almost like a daily journal, recording sights and experiences as he came across them, so it is a more reliable account of day-to-day life in Wales in the last years of the 12th century, and the remnants of Roman Britain:

We went through Caerleon, passing far away on our left Monmouth Castle and the great Forest of Dean, which is across the Wye, but still on this side of the Severn, and which supplies Gloucester with venison and iron ore. We spent the night in Newport. We had to cross the River Usk three times.

Caerleon is the modern name of the City of the Legions. In Welsh ‘caer’ means a city or encampment. The legions sent to this island by the Romans had the habit of wintering in this spot, and so it came to be called the City of the Legions. Caerleon is of unquestioned antiquity. It was constructed with great care by the Romans, the walls being built of brick.

You can still see many vestiges of its one-time splendour. There are immense palaces, which, with the gilded gables of their roofs, once rivalled the magnificence of ancient Rome. They were set up in the first place by some of the most eminent men of the Roman state, and they were therefore embellished with every architectural conceit. There is a lofty tower, and beside it remarkable hot baths, the remains of temples and an amphitheatre.

All this is enclosed within impressive walls, parts of which still remain standing. Wherever you look, both within and without the circuit of these walls, you can see constructions dug deep into the earth, conduits for water, underground passages and air-vents. Most remarkable of all to my mind are the stoves, which once transmitted heat through narrow pipes inserted in the side-walls and which are built with extraordinary skill. [Chapter 5]

But then comes the less reliable (but no less interesting) detail (especially since he says "in our days"):

It is worth relating that in our days there lived in the neighbourhood of this City of the Legions a certain Welshman called Meilyr who could explain the occult and foretell the future. He acquired his skill in the following way. One evening, and, to be precise, it was Palm Sunday, he happened to meet a girl whom he had loved for a long time. She was very beautiful, the spot was an attractive one, and it seemed too good an opportunity to be missed.

He was enjoying himself in her arms and tasting her delights, when suddenly, instead of the beautiful girl, he found in his embrace a hairy creature, rough and shaggy, and, indeed, repulsive beyond words. As he stared at the monster his wits deserted him and he became quite mad. He remained in this condition for many years. Eventually he recovered his health in the church of St David’s, thanks to the virtues of the saintly men of that place.

All the same, he retained a very close and most remarkable familiarity with unclean spirits, being able to see them, recognizing them, talking to them and calling them each by his own name, so that with their help he could often prophesy the future.

The story does not end there. He offered numerous instances of Meilyr's ability to see and speak to devils and demons and learn things from them.

Despite the more fanciful anecdotes, as a record of daily life among the Welsh and Normans, it is a valuable account for modern historians.

As I mentioned, he served several Plantagenets, and we'll take a look at what he thought of Henry II and his sons before we move on. See you tomorrow.