The Sefer Refuot or "Book of Remedies" is the earliest known Hebrew text on medicine. It contains information on illnesses and treatments, but also talks about how to maintain health through exercise, eating properly, and observing proper hygiene. It also suggests that astrology is connected to health, and there are different treatments depending on the month. It includes a code of conduct for doctors.

Although the only manuscripts we have are later medieval ones, they are considered to be faithful copies of a very early work for a particular reason: the book does not have any of the Arabian medical knowledge that was so prevalent in the Middle Ages. The assumption is that this book recorded Jewish knowledge, including a theory of blood vessels and circulation, that pre-dates the cross-cultural sharing that happened with the spread of Muslims after the 7th century.

There was some controversy about medicine in Jewish culture. In II Chronicles 16:12, King Asa of Judah is criticized because “in his illness he sought not God but rather physicians.” In the same book, King Hezekiah is praised for hiding a medical book in order to get his people to turn to God for aid. The 13th-century Nachmanides argued that Jews have a special relationship with God and should thrive or suffer according to His will; they should not try to subvert his will through practices like medicine. Because of this turning to natural cures, he says, their relationship with God in this area has been annulled, and now they have no choice but to turn to doctors. The practice of medicine is now considered a mitzvah, a fundamental religious obligation.

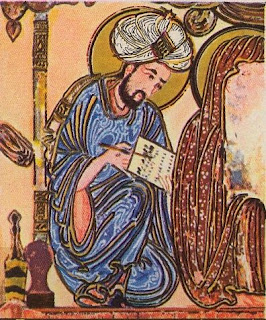

Jewish physicians often learned Latin, Greek, and Arabic; along with Hebrew, they had access to many medical texts inaccessible to their Christian counterparts. This made them exceptionally knowledgeable and effective—and sought after. I've already mentioned Jacob Mantino ben Samuel, who was so important to many high-ranking figures in Venice that they asked the Council of Ten to exempt him from wearing the degrading yellow cap that was mandated to denote Jews in public.

Jewish physicians also included women among their number, not just as midwives, which we will talk about next time.