|

| A copy sold by Christies in 2002 for $688,000 |

The term "legend" at the time was able to convey the idea of truth as well as fiction in this kind of work, and rightfully so. Jacobus was not concerned with creating a well-documented and historically accurate account of saints. He was interested in producing inspiration and enlightenment, and that cannot be left to the facts.

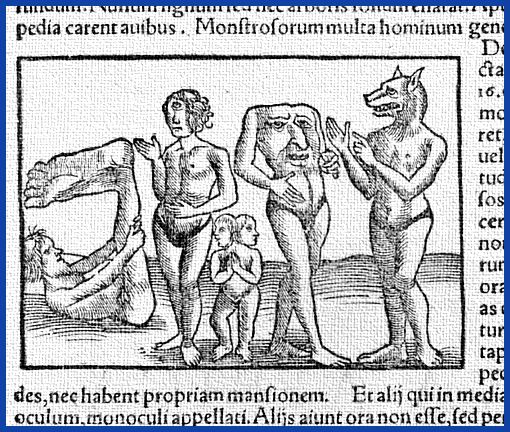

And so we have our major reports of saints such as St. George whose faith enabled him to slay the Dragon, and St. Christopher whose name means Christ-bearer and whose major feat in life was to bear a child across a river who turned out to be Jesus Christ in disguise. The 20th century acknowledges that these saints are likely never to have existed, but for Jacobus their example for Christians is far more important than determining whether they actually lived. He not only told the stories of their lives and major exploits (in great detail), he frequently analyzed their names, explaining their symbolic significance. Jacobus knew Latin, and would have been aware that his interpretations of Latin names was frequently more creative than etymological, but that didn't matter to him as much as holding the saints up as exemplars for proper behavior. He did not, however, take an "anything goes" approach: in his life of St. Margaret, when she is swallowed by a dragon whose belly breaks open due to her prayer, he labels the incident "apocryphal."

Which is not to say that he made everything up on his own. Scholars believe that he was drawing much of his knowledge from previous texts that they can identify. In fact, the 16th century—a time of church reform and re-examination of long-held beliefs and practices—saw a rejection of many of the stories of the Legend because of their fanciful nature. Still, it was an extremely popular work for the masses. William Caxton's English edition in 1483 went to several printings between then and 1527, attesting to its enduring attraction for readers. Although the chapters tend to start sounding the same after a time, it is still studied today as an example of medieval tastes and beliefs.