|

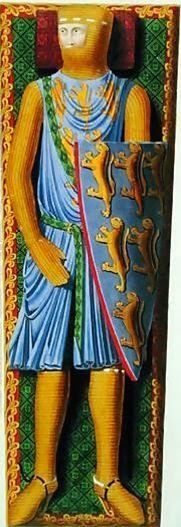

| Henry, the young king. |

For a time, the Capetian Dynasty in France had the habit of naming and actually crowning the king's heir in the old king's lifetime. King Stephen and King Henry II of England adopted this policy. In June 1170, King Henry II crowned his 15-year-old son Henry. Watching the ceremony would have been the 13-year-old Richard (later King and Lionheart), 12-year-old Geoffrey, and 3-year-old John (later "Bad King John").

"Young King Henry" (1155-1183) was considered handsome, charming, and popular; however, he showed no apparent skill or interest in politics, military skill, or even ordinary intelligence. For these reasons, it is probably good that his father never entrusted him with any authority. In fact, Henry II seems to have used his son as a political tool.

- Henry was betrothed to Margaret, daughter of Louis VII of France, on the condition that her dowry would be the Vexin, the border region between the England-held Normandy and France itself. (A nice expansion of England's property on the continent.)

- Because Pope Alexander III needed help dealing with Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, he acquiesced to Henry's request to allow the children to be married in 1160, giving England the Vexin. (There was no ceremony until 1172.)

- Henry had the royal wedding officiated by the Archbishop of York instead of the Archbishop of Canterbury, as was customary. This was likely an attempt to put the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Beckett, in his place. (He would be dead six months later.)

The benefit of naming your heir early was to avoid disputes at the senior king's death over the succession. In this case, however, since young Henry would inherit vast lands with the throne, he was given a house and staff and large income—and even one of the most respected men of the age, William Marshal, as a tutor in arms—but not provinces and territories like his younger brothers. Consequently, his brothers had more power than he. This would have rankled the young king while his father lived on...and on.*

In 1173, Henry the young king led a rebellion with his brothers, his mother, the kings of France and Scotland, the Count of Flanders,

et alia, against his father (this really was the most turbulent family in the Middle Ages). The same qualities and actions that brought Henry II rivals and enemies, however, also brought him great wealth, and he was able to hire sufficient mercenary forces to put down what was later called the Great Rebellion. (It was the English opposition to all the foreign mercenaries on England's soil that prompted Henry to create the

Assize of Arms.)

Young Henry rebelled again in 1183 against his father and his brother, Richard, over Richard's iron-fisted rule of the Duchy of Aquitaine. Henry had the help of his brother Geoffrey and Aquitaine locals who were willing to throw off Richard's rule, but the sudden death of the young king on June 11, 1183, ended the attempt. He was a little over 28 years old. King Philip of France, the brother of Margaret, lost little time in asking for the return of her dowry, the Vexin.** Instead of the land, France accepted an annual payment from Henry II.

Because he never ruled, he is not counted in the list of Kings of England. He is neglected by history in favor of his younger brothers, but he is not without fans: a recent

website is devoted to him.

*

Queen Elizabeth should be glad that the House of Windsor does not appear to have any of the Plantagenet temper.

**

The 1967 movie The Lion in Winter is a highly fictionalized—and highly entertaining—account of this meeting.