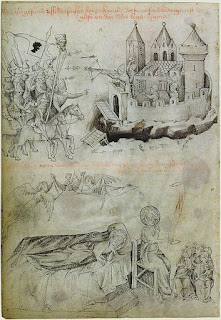

Spies were sent into Poland, Hungary, and Austria for reconnaissance. Having planned their approach, three separate armies invaded Central Europe, into Hungary, Transylvania, and Poland. The column into Poland defeated Henry II the Pious (the illustration shows the Mongol army with Henry's head on a spear).

The second and third columns crossed the Carpathians and followed the Danube, combining with the Poland column and defeating the Hungarian army on 11 April 1241. They killed half the Hungarian population, then proceeded to German territory. Most of the city of Meissen was burned to the ground. Further advances in Germany were paused when the Great Khan died in 1241 and the chief descendants of Genghis returned to Mongolia to elect his replacement.

The Encyclopædia Britannica describes the conflict thusly:

Employed against the Mongol invaders of Europe, knightly warfare failed even more disastrously for the Poles at the Battle of Legnica and the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi in 1241. Feudal Europe was saved from sharing the fate of China and the Grand Duchy of Moscow not by its tactical prowess but by the unexpected death of the Mongols' supreme ruler, Ögedei, and the subsequent eastward retreat of his armies. [EB, (2003) p.663]

Central Europe was not completely helpless. Observations of Mongol tactics meant that Hungary, for instance, improved its heavy cavalry and increased fortifications of settlements against siege weapons. Many smaller hostilities between Central and Western Europe entities were put on hold in the face of the common threat.

Bela IV of Hungary sent messages to the Pope asking for a Crusade against the Mongols. Pope Gregory IX would rather have attention on the Holy Land, although he did eventually agree that the Mongol threat was important. A small Crusade was gathered in mid-1241, but Gregory died in August, and the forces were instead aimed at the Hohenstaufen dynasty.

Mongol attempts to conquer Central Europe continued right up until 1340 with an attack on Brandenburg and Prussia. Fortunately, internal strife in the Golden Horde made Mongol attacks less effective. Lithuania fought back, achieving victory in places including the Principality of Kiev. The Duchy of Moscow also reclaimed many Rus lands. In 1345, Hungary initiated a counter-invasion that captured what would become Moldavia.

I want to go back and talk about the one named casualty in this post: poor Henry II, called "The Pious." We'll look into his reign tomorrow.