Cardinal Pelagio Galvani (c.1165 - 30 January 1230) was the papal legate leading the Fifth Crusade. He hailed from the Kingdom of León, and became a canon lawyer. Pelagio was not a tolerant man: on a two-year mission to Constantinople, he tried to close Greek Orthodox churches and imprison their priests, and action that created so much chaos that the Martin Emperor of Constantinople, Henry of Flanders, reversed Pelagio's acts.

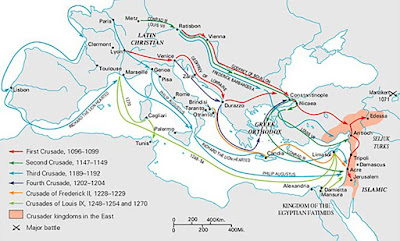

Crusades needed religious leaders as well as military ones, and Pelagio was sent to lead the Fifth Crusade by Pope Honorius III (Pope Innocent II, who had called for the Crusade, had died July 1216, before the Crusade had started out).During the Siege of Damietta, while the Crusading army made some inroads in to Egypt, intending to use it as a staging area from which to conquer Jerusalem (see yesterday's post), the sultan al-Kamil made a peace offering: he would ensure the handover of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to the Crusaders, if they would depart completely from Egypt.

Given the main goal of the Crusades—to control Jerusalem—this would seem to be a win-win, and the secular leaders wanted to accept it. Pelagio, however, along with the Templars, the Hospitallers, and the Venetians, wanted to keep what they had taken. The Templars and Hospitallers would have shared Pelagio's religious reasons for converting the whole world to Christianity. In the case of the Venetians, I suspect they were more interested in the value of Damietta and the Nile as trade routes for their merchant fleets.

The Siege continued to attack Damietta under Pelagio's orders, and a further deal was offered by al-Kamil: this time he included to release any prisoners they had taken and to return the piece of the True Cross that had come into Muslim hands. Pelagio turned this and subsequent offers. Despite arrivals of more Crusader forces, the western army never gained a permanent foothold in Egypt. Finally, on 28 August, even Pelagio realized the Egyptian route was a lost cause. A nighttime attempt to use a canal to make further progress into Egypt on 26 August 1221 resulted in disaster for the Crusaders when the Egyptians detected them and attacked. The defeat was so demoralizing that even Pelagio decided to admit defeat. Two days later, he sent an envoy to al-Kamil. On 8 September 1221, the Crusading army left Egypt, abandoning the Fifth Crusade, having never come close to Jerusalem.

But how is it that sultan al-Kamil had a piece of the True Cross to offer? He got it at the Battle of Hattin, which I'll tell you about tomorrow.