In 778, Basques ambushed the rearguard of Charlemagne's army as it was going northward through the Ronceveaux Pass in the Pyrenees. They

had good reason, and they destroyed the rearguard and the baggage train. In the process, according to Charlemagne's biographer

Einhard, they killed the "prefect of the borders of Brittany," Hruodlandus. Hruodlandus is translated as the name "Roland."

In the 11th century, a poet writing in Old French produced a 4000-word epic poem, La Chanson de Roland ("The Song of Roland") that turned the incident mentioned briefly by Einhard into the foundation of a literary cycle called the Matter of France. It tells a very different story from Einhard's brief description.

Instead of being pursued by Basques whose chief city of Pamplona had its walls torn down by Charlemagne's army on his way home, the poem has Charlemagne's army fighting Muslims in Spain for seven years. The last holdout is the city of Saragossa, ruled by Marsile. Marsile promises treasures to Charlemagne and that he will become a Christian if Charlemagne will leave and go home.

Charlemagne is satisfied with this. His nephew, Roland, selects Roland's stepfather Ganelon to carry the message of acceptance to Marsile. Ganelon, afraid that Roland wishes him ill by sending him to where Muslims might kill him, betrays them all by telling the Muslims how to ambush Charlemagne's army as they pass through Roncesvalles. The rearguard, led by Roland with comrades Oliver and Archbishop Turpin, finds themselves overwhelmed.

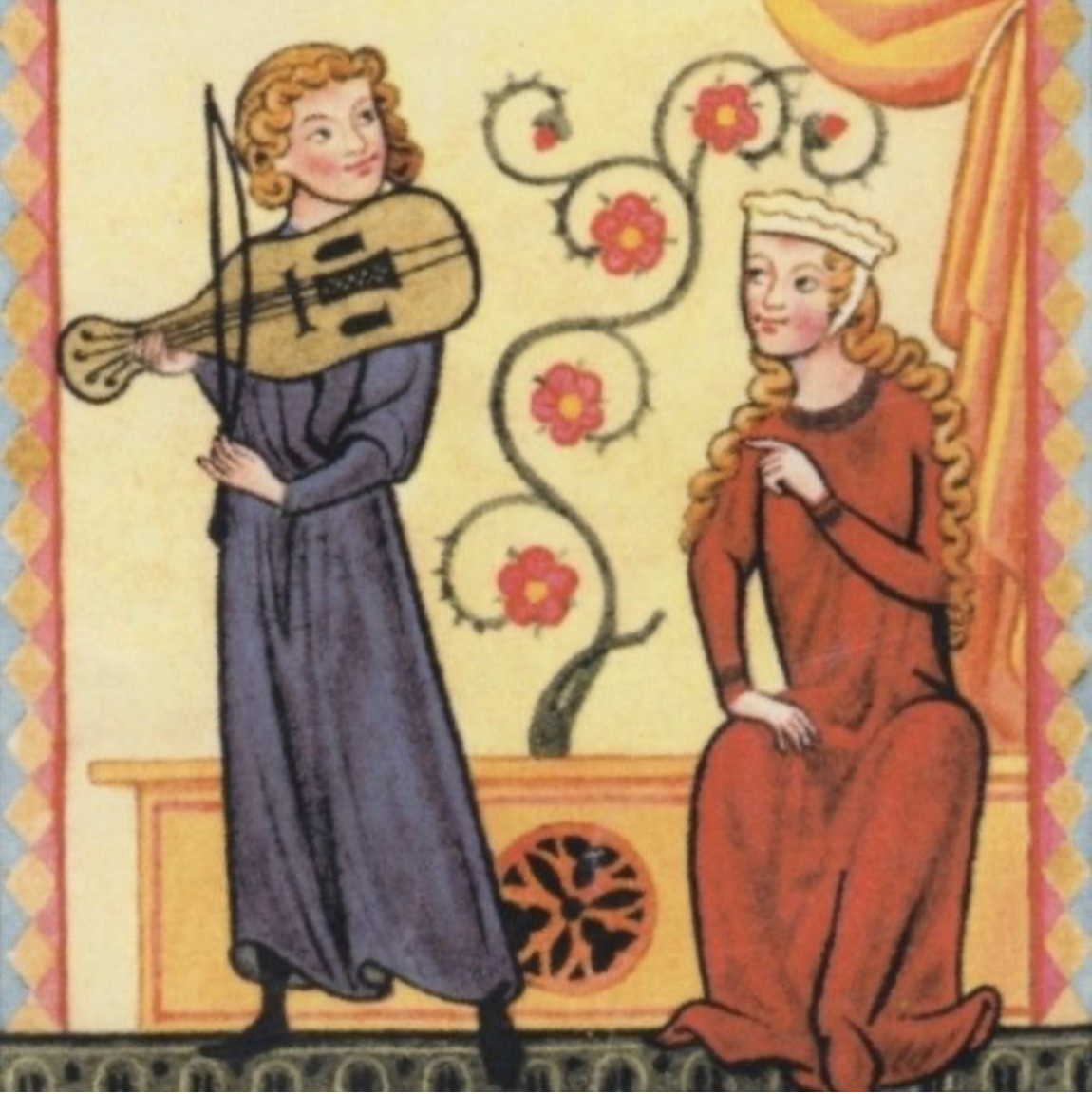

Oliver tells Roland to blow his horn and summon reinforcements. Roland believes that would be an act of cowardice. Roland, however, loves Oliver's sister, so Oliver tells him that Roland will not be allowed to see his sister again if he does not summon help. It is Turpin who ultimately convinced Roland to blow his horn (in the illustration above). Emperor Charlemagne hears the horn and starts back, but takes too long because Ganelon delays him. With Roland's men dead or dying, he blows the horn one more time so powerfully that his temples burst. He is taken to Heaven by angels.

Charlemagne finally arrives, finds Roland and all his men dead, and pursues the Muslims into the River Ebro where they drown. While burying their dead, the Franks are attacked by Baligant, emir of Babylon, who has come to support Marsile. The armies fight, Charlemagne kills Baligant, the Muslims flee, and Charlemagne now conquers Saragossa, returning home with Marsile's queen.

Ganelon's betrayal is discovered, and he is imprisoned; he argues that he acted out of legitimate revenge against his stepson, not treason against the emperor. Although Ganelon's friend, Pinabel, will fight anyone who claims Ganelon is guilty of treason, Thierry convinces the council of Barons that it was treason, since Roland was serving Charlemagne at the time of the betrayal. Pinabel challenges Thierry to trial by combat, Thierry kills Pinabel, Ganelon is executed by having four horses tied to him, one to each limb, and set to gallop.

There are many improbabilities and impossibilities here, not least of which Charlemagne did not become an emperor until many years later, and an "emir of Babylon" is unlikely to appear in northern Spain, thousands of miles west of Babylon. The poem became an important literary and cultural touchstone for medieval France, however. I referred above to the "Matter of France." There were three great "Matters" in the Middle Ages, and I'll tell you more about them tomorrow.