You may have seen medieval coins that weren't entirely round; they were lop-sided somehow or had a flat edge to them. That was not necessarily the action of years or wear and tear through handling. That was more likely because of coin-clipping.

Coin-clipping was a popular way to make more money for personal use. Medieval coins were solid metal all the way through, not cheaper metal covered with another layer to make them shiny, as much modern coinage is in the promissory system. The Medieval English penny was solid silver. A known practice was to "clip" the edges of the coin, reducing its size, and using the clipping from several coins to make an additional coin (or a silver lump that had value).

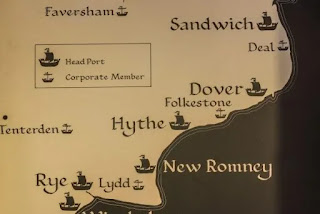

This, of course, debased the value of the original coin(s) because they were expected to have a specific weight of silver (or gold, in some cases). The illustration above is not medieval, but from a hoard of clippings from 16th century coins found in 2015.

One of the ways to guard against coin clipping was to put a design or milled edge on the coin to make it clear of the edge has been altered; United States quarters and dimes show this, nickels and pennies are made of such cheap metal that a milled edge isn't considered worthwhile.

Other methods of debasing coinage were "sweating" and "plugging." In sweating, coins were placed in a bag and shaken vigorously so that bits of metal might flake off and could be collected at the bottom of the bag to be re-used. Plugging was the act of punching a hole in the middle of the coin, knocking out a bit of metal, then hammering the coin to fill in the hole. With the edge of the coin intact, the flattened image in the center could be explained as normal wear and tear.

These practices were bad for the economy, devaluing the actual coin (which was based on weight of silver), and promoting inflation. They were considered extremely serious offenses. Suspicion of coin-clipping in the time of King Edward I (1272-1307) lead to hundreds of deaths in a single outrageous over-reaction.

But that's a story for tomorrow.