At this time, Danish incursions into England had sacked and destroyed many monasteries. Monastic life in England was at a low point. Dunstan, who like Æthelwold was later made a saint, adopted the Rule of St. Benedict (mentioned a few times) for the Glastonbury monastery, and led the revival of monasticism in England. Dunstan, Æthelwold, and Oswald of Worcester and York would be called the "Three English Holy Hierarchs" for their work in reviving English Orthodox monasticism.

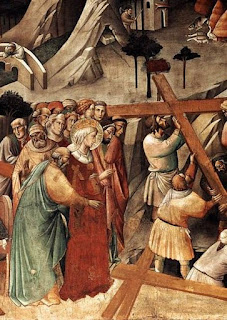

Æthelwold wanted to go to Cluny in France to experience their version of monasticism, but Dunstan and then-King Edred did not want to lose him, and they sent him to Abingdon-on-Thames to run the derelict monastery there. The patron saint of the place was St. Helena, because legend had it that she built a church there.

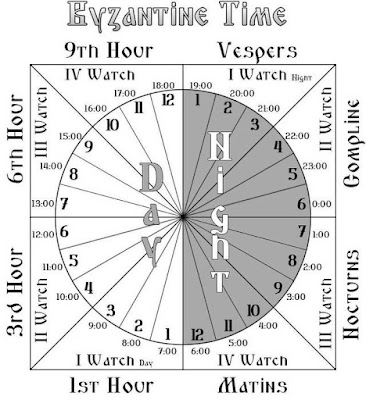

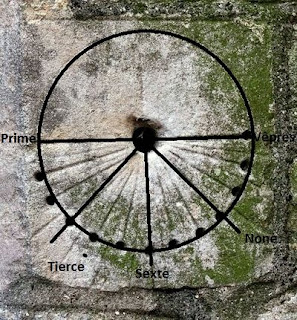

Abingdon became a strong monastic community. Æthelwold brought singers from Corbie in France to teach Gregorian chant, which was not common at the time in England.

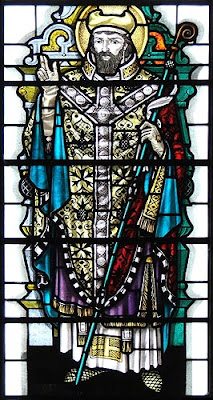

When Æthelwold became Bishop of Winchester in 963, the priests were illiterate, lazy, guilty of drunkenness and gluttony; they were not good at the services, and most were married men. Æthelwold expelled the married men, tightened up discipline, and brought in monks from Abingdon as the nucleus of a new "monastery/cathedral" institution.

I'll say a little more about him tomorrow, including about the miracles attributed to him.