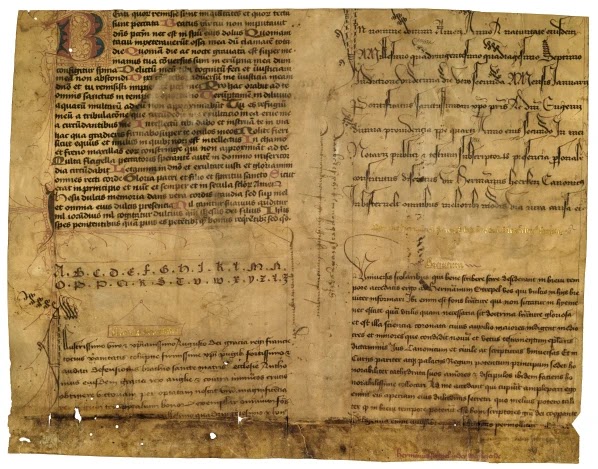

With his knowledge of Latin and Greek, he analyzed classical texts and wrote treatises on them. One of his bars to working for the papacy may have been his work that established the Donation of Constantine as a forgery. I previously wrote about him and the Donation here.

He likewise showed the inauthenticity of a supposed letter from Christ to Abgar (1st century ruler of Edessa). His questioning of other religious documents and his questioning of the usefulness of monastic life roused the ire of faithful churchmen. One of his fiercest enemies was Bracciolini, who pointed out errors of style in Valla's works and made ad hominem attacks on Valla, accusing him of degrading vices.

Bracciolini attacked Valla's major work on Latin language and style, in which Valla argued that biblical texts could be subjected to the same analysis and critiques on the basis of style the way non-biblical classical texts could. Bracciolini argued that the new humanism was to be considered separate from theology, and profane and sacred writings were to be treated differently. He penned five Orationes in Laurentium Vallam ("Orations to Lorenzo Valla") criticizing him, which was countered by Valla writing Antidota in Pogium ("Antidote to Poggio").

Surprisingly, the two men were reconciled, prompted by other scholars and humanists. They acknowledged each other's talents, and became friends. Erasmus considered Valla superior to Bracciolini, saying Poggio was "a petty clerk so uneducated that even if he were not indecent he would still not be worth reading, and so indecent that he would deserve to be rejected by good men however learned he was." (Erasmus had probably seen and disapproved of Bracciolini's joke book.)

Although never became an apostolic secretary, he was invited to Rome by Pope Nicholas V to work on a special project: the new Vatican Library. Let's talk about that place tomorrow.