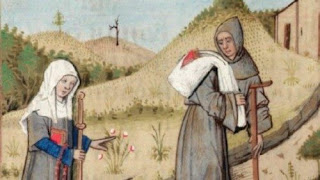

His father and grandfather were pharmacists, and his uncle taught medicine. Mondino himself taught medicine and surgery at the University of Bologna from 1306 to 1324. In 1316 he published an illustrated manual of details of the inside of the human body (sample to the left). The Anathomia corporis humani ("Anatomy of the human body") was the first of its kind.

He theorized a hierarchy of body parts based on what he considered most important. The abdomen was the "least noble" part of the body, and so should be dissected first. The thorax came next, and last was the head with its "higher and better organized" structures (the organs of the senses: eyes, ears, mouth). He also discussed different methods of dissection between simple versus complex structures, like muscles and arteries versus eyes. When dissecting muscles, he suggested letting the cadaver desiccate, rather than mess with a decaying cadaver. The Anathomia was a manual to explain Mondino's proper methods for dissection.

That doesn't mean he was right about everything. He claims the liver has five lobes, the stomach is round and its internal lining is where sensation happens and the external layer is where digestion takes place. He apparently never found an appendix in a cavern, even though he examined many intestines. He says the heart has three chambers, not four. Still, the text became a standard in medical knowledge for 300 years.

Mondino wasn't much interested in pathology of disease, which is just as important to medicine as understanding how the physical; body works, if not more so. Fortunately, there were others—contemporaries of Mondino's, in fact—of whom we shall speak...tomorrow.