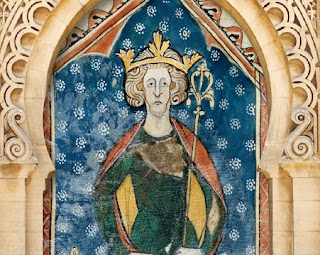

Henry was a king of England who did not speak English: he spoke only Latin and French. During his reign, Henry ruled much of England, gained control over Wales, and held substantial land on the continent. He had been named Duke of Normandy (in northwest France) in 1150, and became Duke of Aquitaine (in southwest France) in 1152 upon his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine. He also had occasional control over Scotland and Brittany.

He was described as a short, stocky, good-looking redhead, bow-legged from all the horseback riding. He was reported to have great energy, which he applied to (among other things) reforming/standardizing royal law, where previously there had been several variations due to local tradition. His reign resulted in the first comprehensive treatise on English law, the Treatise of Glanvill, which is worth taking a look at...next time.