20 July 2022

The Flemish Revolt, Part 1

19 July 2022

Attacks on Flemings

Whan Adam delf, and Eve span,This was part of a sermon allegedly delivered in Blackheath the night before that group of peasants descended upon London during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. Although the catalyst for the Revolt may have been a poll tax, resentments against the upper classes were always ready to boil over. Flemings were not generally a large part of the countryside peasant population.

Wo was thanne a gentilman?

Flemings were, however, mentioned specifically in one account of the Revolt, and it has two curious features. The account in MS Cotton Julius B.II. ends with the lines:

...and many fflemynges lost here heedes at that tyme, and namely they that koude nat say 'breede and chese", but "case en brode".

It was curious that Flemings were mentioned specifically. Also, contemporary references to language in the 14th century are extremely rare, so why distinguish these foreigners with a reference to their tendency to idiomatically express "bread and cheese" as "case and brode." (Modern German for cheese is still "Käse" and for bread is "Brot" with a long ō sound.)

One of the targets for destruction was the "stews" or brothels of Southwark, just south of London across the Thames. It was an area well known for prostitution, and that particular profession at that time was dominated by Flemings. One particular Fleming-run brothel was invaded and destroyed by the mob, but it was owned by the mayor of London, William Walworth, so the destruction may have been aimed at him as a representative of the upper classes—in the spirit of the first quotation above—rather than the foreigners specifically.

18 July 2022

To be Flemish

The term "Flemish" has been used since the 1300s to refer to a certain group of people. What does it mean to be Flemish?

The word "Flemish" was first seen in print c.1325 as flemmysshe, although Flæming had been around since at least 1150, meaning "from Flanders." Flanders was originally a small territory around Bruges, established in the 8th century. Flanders now is the Dutch-speaking northern part of Belgium. The Flemings currently make up about 60% of the Belgian population.

Is there a Flemish language? The Flemish language is sometimes called Flemish Dutch, or Belgian Dutch, or Southern Dutch. In the illustration of Belgium to the left, the dark green area is where Dutch is spoken, the light green area is mostly French-speaking. (There is a small German area on the far right, and the lighter spot among the dark green is Brussels itself, where both Dutch and French have official status.

In 1188, Gerald of Wales (a historian mentioned, among other places, here) described the Flemings as:

a brave and sturdy people […] a people skilled at working in wool, experienced in trade, ready to face any effort or danger at land or sea in pursuit of gain; according to the demands of time and place quick to turn to the plough or to arms; a brave and fortunate people.

Gerald knew about them not because he traveled to the continent, but because many Flemings left Flanders due to population growth and the need for more land, many ending up in Scotland. In fact, the surname Fleming is fairly common these days, mostly because of Flemish families in Western Europe.

Flemings are even mentioned in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, in a reference that raises its own set of questions, but we can talk about that tomorrow.

17 July 2022

John van Ruysbroeck

That uncle, Fr. John Hinckaert, arranged for his nephew's education with the intent for him to join the priesthood. Join the priesthood he did, in 1317, at St. Gudule's. (His mother tracked him down in Brussels and joined a beguinage; she died shortly before his ordination.)

His uncle, and therefore by influence van Ruysbroeck himself, practiced an apostolic austerity that was becoming popular among lay people such as the Beguines. The groups that followed this lifestyle often developed their own tenets that clashed with the preferences of the Church. van Ruysbroeck wrote pamphlets against some of these "heresies," especially to counter the writings of a particular Brussels woman in the Brethren of the Free Spirit named Bloemardinne. van Ruysbroeck was not opposed to these groups and their desire to live a more simple and saintly life—he followed that urge himself—but he did not want those doing so to stray from orthodoxy.

His own desire for a less worldly life led him away from the Cathedral of St. Gudule. (Partly he seems repulsed by how his own writings against Bloemardinne kicked off a persecution of her.) He, his uncle, and his uncle's close friend, a fellow canon named Francis van Coudenberg, left the Cathedral to form a hermitage in 1343, in Groenendael. The Groenendael hermitage became very popular, and drew so many followers that the three had to organize it into a regular congregation, of which it became the motherhouse.

van Ruysbroeck did most of his writing during this period, including twelve books, all in Middle Dutch. One of them, The Twelve Beguines [link], discusses "different notions of the Love of Jesus" in a conversation between 12 Beguines. This book, so complimentary to the Beguines, as well as his reputation as a mystic, explains why he was at one time considered to be the author of A Mirror for Simple Souls, when its true author, Marguerite Porete, was temporarily unknown.

He passed away on 2 December 1381, leaving behind a massive reputation for holiness and wisdom. He was honored as a saint and his relics preserved, although they were lost during the French Revolution. He was beatified on 1 December 1908, although the pressure to have him canonized has abated. The illustration above is a common image for him: writing alone in the woods while caught up in mystical ecstasy.

And now for something completely different, to combat my own ignorance. While writing the opening sentence of this post, I found myself questioning the word "Flemish" and realizing that I did not have a firm grasp on its meaning. What does/did it mean to be Flemish? Does it refer to a language, a people, a place? I know very well there is no "Flemland." What did the Middle Ages consider to be Flemish? Let's find out together, tomorrow.

16 July 2022

Marguerite Porete

Her subject was the transformation of the soul through agape (Christian love, as distinct from physical or emotional love). Using poetry and prose, she outlined seven stages of the soul on its path to Union with God.

The more important issue with the book was that it expressed ideas similar to those of the Brethren of the Free Spirit, a loose movement in the Low Countries between the 13th and 15th centuries. Some of those ideas were that Christ, the church, and the sacraments were not necessary for salvation, because the soul could be perfected on its own by connecting to God's love. In fact, the perfection of the soul meant that the soul and God were one.

Her book was copied and spread among Beguines and others. Authorities rounded up all the copies they could find, burned them, and then imprisoned Marguerite. She spent a year and a half imprisoned, speaking to no one. Finally, a trial was held, during which she refused to renounce the ideas expressed in the Mirror, or to promise to never express them again.

Her refusal led to her burning at the stake on 1 June 1310. Although it remained popular after the trial, and was widely circulated, Le Mirouer des simples âmes was known to modern times only through the record of her trial. In 1911, a purchase of old manuscripts by the British Library from a private collector turned up an English translation made in the 15th century. Three other manuscripts were eventually found, one in Latin. Various translations have been published since then.

There was a time when the copies circulated after her death were wrongly attributed to another author, John van Ruysbroeck. What made him a likely candidate for this mistake? We will meet him tomorrow.

15 July 2022

The Beguines End

Their Christian attitude did not always exist in their neighbors, or in the Church. Although Cardinal Jacques de Vitry supported them, and the Bishop of Lièges even created a rule for them, some communities cast an unkind eye upon the Beguines because of their ambiguous social status: they lived "in the world, but were not of it."

Beguines became viewed as ostentatious in their lifestyle, as hypocritical because they did not commit to a religious Rule, and even as obnoxiously superior to cloistered religious: the founder of the Sorbonne, Robert de Sorbon, pointed out that they were far more devoted to God than monks, since they pursued the religious life without vows and without being removed from the temptations of the world. This realization could annoy small-minded laity and clergy alike.

There is also the chance that the Church resented a large religious group over which they had no formal control. One well-known Beguine, Marguerite Porete, was burned at the stake on 1 June 1310 because of a book she wrote that was considered heretical. A year later, the Council of Vienne discussed the nature of the human soul. Because the Beguines believed the human soul could be perfected by proper Christian behavior in this world, the Council condemned them as heretics. This same Council condemned the Knights Templar, removing the pope's support from them at the instigation of the French king.

There are Beguines (or Beguine-ish) groups today: the Company of St. Ursula, and recent groups in Vancouver, America, and Germany. The Church also allows "Consecrated Diocesan Hermits," but they must take their formal vows in front of a bishop; then they can live on their own.

But let's go back to Marguerite Porete and find out what she and her book were about more specifically. See you next time.

14 July 2022

The Beguines Begin

In the early 1100s, some women in the Low Countries (where the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg are now) began devoting themselves to a simplified life of prayer and charitable work. They did not take formal vows of poverty or obedience as nuns would—though they embraced chastity—and there was no compulsion to remain in their chosen lifestyle, if for some reason they decided to change.

The trend among women grew, however, until in the following century it was apparent that this was a movement that stood out among towns and villages. Many women would move to be near each other, forming communities for mutual support. Local clergy would point to them as exemplars of Christian behavior. Jacques de Vitry even appealed to the pope to recognize them formally.

These groups never gained formal recognition by the pope, but local churches encouraged the behavior, even help establish the communities, called beguinages after the name Beguine. (The origin of "Beguine" is unknown; a theory that it came from a priest named Lambert le Bègue, "Lambert the Stammerer" seems unlikely.) Some of these communities were huge: The Beguinage of Paris had 400 women, one in Ghent had thousands of members.

Eventually the Beguines fell out of favor, especially after the Council of Vienne; why that happened will be the subject for tomorrow.

13 July 2022

Jacques de Vitry

Born at Vitry-sur-Seine (hence the surname) near Paris about 1160, he studied at the recently founded University of Paris. After an encounter with Marie d'Oignies, a female mystic, he was convinced to become a canon regular (a priest in the church, as opposed to a monk), so he went to Paris to be ordained and then served at the Priory of Saint-Nicolas d'Oignies. He strongly preached for the Albigensian Crusade.

On the other hand, he was fascinated by the Beguines, a lay Christian group that operated outside the structure of the Church, and asked Honorius to recognize them as a legitimate group.

His reputation was such that in 1214 he was chosen bishop of St. John of Acre, in the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem. From that experience he wrote the Historia Orientalis, in which he recorded the progress of the Fifth Crusade, as well as a history of the Crusades, for Pope Honorius III. He never finished the work. Besides leaving many sermons, he also wrote about the immoral life of the students at the University of Paris.

In 1229, Pope Gregory IX made de Vitry a cardinal. A little later he died (1 May 1240) while still in Jerusalem. His body was returned to Oignies. His remains were held in a reliquary. In 2015, a research project determined that the remains in the reliquary likely were, in fact, de Vitry's. Forensic work on the skull and DNA evidence contributed to a digital reconstruction of his head and face.

The Beguines were only mentioned here briefly, and deserve more attention. They will come next.

12 July 2022

Christina the Astonishing

At her funeral, during the Agnus Dei, she suddenly rose up from her opened coffin with great vigor. It is reported that she rose in the air up to the rafters of the church. The priest told her to come down; she landed on the altar and announced that she had seen heaven and hell and purgatory, and had been returned to earth to pray for those stuck in purgatory.

According to Dominican professor of theology at Louvain Thomas de Cantimpré, who wrote a biography after interviewing witnesses, including Cardinal Jacques de Vitry, her life changed radically from that point. She claimed she could not abide the odor of sin she smelled on people, and would climb trees or levitate to avoid them. She started sleeping on rocks, wearing rags, and seek other forms of deprivation or mortification.

She would stand in the freezing water of the river Meuse, roll in fire without harm, hang out in tombs (according to the report by Vitry). She would claim at times to be leading recently deceased to purgatory, and leading souls from purgatory to heaven. Her neighbors had differing opinions: some called her a holy woman touched by God, some said she was insane. The prioress of the nearby St. Catherine's convent remarked that Christina was always docile and obedient when the prioress asked her to do something, regardless of her bizarre behavior at other times. She lived her remaining days at St. Catherine's.

Although never formally canonized (and therefore sometimes referred to as Blessed Christina instead of St. Christina), she was nevertheless added to the Tridentine calendar with a feast day of 24 July, the day of her death in 1224.

Jacques de Vitry has cropped up a few times over the years in this blog, but has never been discussed directly. I want to rectify that tomorrow.

11 July 2022

Thomas of Cantimpré

Born in a small town in Brussels in 1201, he was sent at the age of five to school in Liège to study the trivium and quadrivium. When he was 16, he was ordained a priest, but after 15 years at Cantimpré he entered the Dominican order and was sent to Cologne for more advanced studies in theology, which he did under Albertus Magnus. He moved a few more times, but near the end of his life traveled throughout Germany, France, and Belgium with the title "Preacher General."

Thomas wrote many works, some of which were copied again and again, and even published in later centuries. One of them, De natura rerum (On the nature of things), had 22 chapters ranging from human anatomy, sea monsters, "Monstrous men" of the East (including cynocephali), astrology, trees, animals, eclipses and planets, etc. He included in this encyclopedia information from Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, St. Ambrose, William of Conches, and Jacques de Vitry.

His other major work used a metaphor of bees in a hive to discuss moral and spiritual edification. Bonum universale de apibus ("Universal good for the bees") has one item I want to mention. Back here, we saw the Statute of Kalisz established that Jews could not be accused of blood libel, the kidnapping of children to use their blood for rituals. This was common for centuries. Thomas came up with a "logical" explanation of blood libel, or blood accusation. Thomas refers to the New Testament passage in Matthew 27:25, when the Jews tell Pilate "May his blood be on us and on our children." Jews killed Christians and used their blood, so the theory went, in order to release themselves from their ancestors' self-imposed curse.

He also wrote several biographies of saints, one of whom was born in Belgium like him. Let's talk about Christina the astonishing next time.

10 July 2022

Dog-headedness

The Greeks may have been influenced by Egyptian gods with canine heads, and not just the jackal-headed Anubis; Wepwawet (originally a war deity) had a wolf head, and Duamutef (a son of Horus) had a jackal's head. The Greek physician Ctesias wrote two books in the 5th century BCE, Indica and Persica, about Persian and Indian lands, of a tribe of Cynocephali:

They speak no language, but bark like dogs, and in this manner make themselves understood by each other. Their teeth are larger than those of dogs, their nails like those of these animals, but longer and rounder. They inhabit the mountains as far as the river Indus. Their complexion is swarthy. They are extremely just, like the rest of the Indians with whom they associate. They understand the Indian language but are unable to converse, only barking or making signs with their hands and fingers by way of reply... They live on raw meat. They number about 120,000.

The best-known dog-headed personage was St. Christopher, who was sometimes depicted in the Eastern Orthodox tradition as dog-headed. This was likely a misunderstanding of an expanded history for him that referred to him as a Canaanite; this was mis-read as "canine-ish" and resulted in him being portrayed as a Cynocephalus who came from their tribe.

St. Augustine of Hippo in his The City of God addressed the topic of the Cynocephali. He accepted that they might not exist, but if they did exist, were the human (which to him meant mortal and rational). If they were both mortal and rational, then they were human, and therefore could have come from nowhere but a line of descendants from Adam.

Ratramnus (died c.868), a Frankish theologian, was concerned about the Cynocephali, because if they were human, then it was obligatory to bring Christianity to them.

Even Marco Polo mentions them:

Angamanain is a very large Island. The people are without a king and are Idolaters, and no better than wild beasts. And I assure you all the men of this Island of Angamanain have heads like dogs, and teeth and eyes likewise; in fact, in the face they are all just like big mastiff dogs! They have a quantity of spices; but they are a most cruel generation, and eat everybody that they can catch, if not of their own race.

The one medieval writer who personally encountered anything approaching Cynocephali was Ibn Battuta (who was mentioned in passing a week ago regarding the Richest Man of All Time):

Fifteen days after leaving Sunaridwan we reached the country of the Barahnakar, whose mouths are like those of dogs. This tribe is a rabble, professing neither the religion of the Hindus nor any other. They live in reed huts roofed with grasses on the seashore, and have abundant banana, areca, and betel trees. Their men are shaped like ourselves, except that their mouths are shaped like those of dogs; this is not the case with their womenfolk, however, who are endowed with surpassing beauty.

Between India and Sumatra is a tribe, the Mentawai, who practice the art of tooth sharpening. He may have encountered them.

Dog-headed humanoids were widespread in literature, mentioned in the Nowell Codex (that contains Beowulf); in a Welsh poem where King Arthur fights them in Edinburgh; lamented at by Charlemagne (in his biography) that he never had a chance to go to war against such a foe; in a Flemish Dominican's popular encyclopedic work corroborating their existence; and many more examples. After the European discovery of the continents west of the Atlantic Ocean, assumptions that the Cynocephali would be found were renewed.

But enough of that. Lots of options to move on from here, but I want to explore that Flemish Dominican who wrote some works that became very popular, based on the number of surviving manuscripts. Next time we will talk about Thomas of Cantimpré.

09 July 2022

Saint Christopher

It is possible he did not exist.

And why was he pictured with a dog's head?

If you know one thing about St. Christopher, it is the story that he helped carry a child across a river, only to find later that the child was Christ. The fact that his name actually means "Christ-bearer" suggests that this was a made-up example of Christian charity. (Consider as well the story of Jesus on his way to Calvary and the woman who wipes his face, only to find his image on the cloth; her name is Veronica, "true image.")

There was supposedly a martyr named Christopher who was killed in either the reign of Emperor Decius (249-251) or Emperor Maximus Daia (308-313). The fact that churches were dedicated to him does not prove his historicity. Pope Paul

But why the dog head? Well, a thousand years after the martyr first lived, the Legenda Aurea (The Golden Legend, a book of saints' tales) says he was a Canaanite originally known as Reprobus (again, a suspiciously apt name meaning "rogue" or "unprincipled person"). Reprobus strove to serve the mightiest lord available, and even served the devil, until at last he found Christ and converted. Then...

The pagan king of Lycia took him as a fool and beheaded him after torturing him. Before his ordeal, however, St Christopher instructed the king to make a little clay mixed with his blood to rub on his eye (which was blinded by an arrow that had been meant for St Christopher). The king did as he was told and said, ‘in the name of God and St Christopher!’ He was healed immediately and was converted to Christianity. St. Christopher performed his miracle in martyrdom. [link]

And this is why he is depicted with a dog's head in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, because they mis-read "Canaanite" for canineus (canine), and assumed he was a member of the race of Cynocephali, the dog-headed people.

And we will learn about them tomorrow.

08 July 2022

The Canine Saint

In life, Guinefort was a greyhound.

The story is brought to us by Dominican monk Stephen of Bourbon (1180 - 1261) in 1250. A knight in Lyon left his baby to go hunting, secure that his faithful dog, Guinefort, would guard the child. When he returned, the dog's mouth was all bloody, the room a mess, the crib overturned, and the baby nowhere to be found. In a fit of sudden rage, the knight cut off Guinefort's head. Hearing a child's cries, they discovered him under the cradle, surrounded by the bloody body of a viper with dog bites all over it. Regretting his killing of Guinefort, they made a grave of stones surrounded with a grove.

Locals, learning of the dog's actions and martyrdom, visited the site more and more. It became a place to bring ill children, or mothers worried about the outcome of their pregnancy, to pray for the intercession of "Saint" Guinefort.

Finding this, Stephen of Bourbon records that he had the dog's bones disinterred and destroyed; the trees were burned down. He shows sympathy for the heroic dog so unjustly killed, but a dog saint? Not on his watch!

It was not allowed for a dog to become a saint, but was it possible for a saint to be a dog? Let me tell you about St. Christopher (yes, that one) tomorrow.

07 July 2022

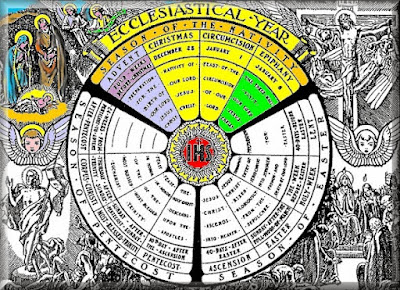

The Tridentine Calendar

Among other things, Trent determined the liturgical calendar (see illustration). Part of this process involved establishing definitive feast days for saints, which may not be altered or added to except by the pope.

In the process, it was necessary to decide definitively which saints deserved feast days or other types of mention. Pope Pius V (ruled 1566 to 1572) removed some names he considered insignificant, such as St. Elizabeth of Hungary (mentioned here) and St. Anthony of Padua (mentioned here). How to determine of saints were worthy of inclusion in the liturgical year, with their names to be specifically mentioned at Mass, was to rank them. The 13th century created a ranking system of Double, Semidouble, and Simple. Pope Clement VIII created the rank of Major Double in 1602. Over the centuries, popes added or subtracted (mostly added) saints' rankings to the calendar. What do these terms signify about the saint in question?

As it happens, we do not know why the word "double" is used; it may have to do with the antiphon (a chant used as a refrain) were doubled before and after the psalms. Another theory is that in Rome before the 9th century it was customary to have two sets of Matins (prayers at dawn) on major feast days. Whatever the origin, the importance of a saint's feast day could be designated (in ascending order) as Simple, Semidouble, and Double; the Double rank included further strata (in ascending order) of Double, Greater/major Double, Double of the II Class, Double of the I Class.

With "semantic satiation" occurring by now, and the word "double" looking and sounding strange to the reader, we have to ask "Why?" What need was satisfied by ranking saints' days?

Well, a saint's feast day had its own liturgy, unique from the ordinary Sunday Mass. If a saint's day feel on Sunday, which Mass do you celebrate? Easter had a special Mass; what do you do if Easter Sunday happens to fall on 17 April, the Feast Day of the 2nd century Pope Anicetus? Sure, he fought against Gnosticism and was (supposedly) martyred—and already has more than one mention in this blog—but is he worth more than Easter? Well, his rank is Simple, so no, Easter liturgy takes precedence. (Actually, Easter takes precedence over every saint; I just wanted an example of a floating holiday.) This overlapping of important days was called an "occurrence"; the lower-ranking day could be referred to as a "commemoration" during the liturgy of the higher-ranking day.

On an ordinary weekday, the priest celebrating Mass can choose to use a liturgy of his choice: either a normal "votive Mass" or Mass for the dead (if a funeral was needed), or he could choose the liturgy for martyrs Cosmas and Damian on 27 September.

There were so many changes to this system that going into more detail would require listing all the revisions over the years, so we will just jump to the later 20th century. Pope Pius XII in 1955 abolished the Semidouble rank, turning them all to Simples (making the choice of which liturgy to perform easier), and reduced all Simples to Commemorations (so no liturgy, just an "honorable mention" during Mass if desired). Pope Paul VI in 1969 further simplified the liturgical choices, eliminating Commemorations and reforming other ranks to Solemnities (truly important days involving the Trinity, or Jesus, Mary, Joseph, or VIP saints; these days include a Vigil), Feasts (pretty much just the Nativity and the Resurrection), and Memorials, most of which were optional.

Thousands of men and women were designated saints in the first 1400 years of Christianity, and at least one dog. Recent centuries trimmed down that list, recognizing that many were likelynot real people, but simply anecdotes intended to teach a moral lesson.

Except the dog; that one happened. You probably want that one explained.

06 July 2022

The Saint Beneath the Stairs

The story goes that Alexius was born into one of the most prominent families in Rome in the 4th century, the son of Euphemianus, a Christian. The family was liberal with its wealth, with many offerings to the poor. Alexius grew up well-educated, steeped in a tradition of generosity, wanting for nothing; in turn, he was the pride and joy of his family.

By and by, his parents arranged a marriage to a young woman of great virtue and wealth. The wedding was grand and the wedding feast lavish. Later that day, however, Alexius was overcome with the urge to give up his wealth, his home, and his new bride. He went to her, giving her to take as tokens of his love jewels and riches. He then went to his own room, changed out of his sumptuous wedding garb, and left the household secretly. He went straight to the harbor and took the first ship to Edessa in Syria.

His disappearance caused his parents to send searchers high and low for him, but of course they never found him. He was living in voluntary poverty in Edessa, giving away all he had and clothing himself in rags. He fasted, slept for a few hours in the vestibule of a church dedicated to Mary, prayed all night, and spent an hour each day begging for alms. This style of living altered him so much that his friends and family would not recognize him. In fact, his parents' servants traveled as far as Edessa in search of the young man, and he was able to beg for alms from them without them recognizing him.

One day, the curate of the church where he resided heard a voice coming from the statue of Mary saying that the poor man in the vestibule was a servant of the Almighty whose prayers were very agreeable to God. The curate spread the word of this, and Alexius began to be visited and praised. This was the opposite of the humility he sought, and so he determined to leave Edessa. The first ship he took went to Rome. He was inspired by God to go to his father's house where, upon encountering his father, he said “Lord, for the sake of Christ, have compassion on a poor pilgrim, and give me a corner of your palace to live in.” Euphemianus, a pious man, took in the unrecognized son, instructing his servants to give him a place to stay and daily food. He was given a cubby under the stairs, where he stayed for 17 years, except for visits to church. Seeing his parents and bride still grieving for him was torturous, but he determined to remain anonymous, lest he be unwillingly returned to a life of luxury and leisure. When he felt his death was near, he went to Mass and Communion, went back home and wrote a brief biography of his years since his wedding night, folded it and held it in his hand. He then died peacefully.

Meanwhile, at Mass attended by Euphemianus and Emperor Honorius(384 - 423), and celebrated by Pope Innocent I (d.417), a voice was heard proclaiming that the servant of God at the house of Euphemianus was dead. The Pope and the Emperor accompanied Euphemianus to his house where they found the holy man dead, the paper held tightly in his hand until by praying the Pope was able to take it from him. They were all astonished at the reading. The house of Euphemianus was turned into the first church dedicated to Alexius.Of course, as "detailed" as a story of a saint's life may be from 1600 years ago, we have to cast some doubt on it. There are several versions of this story. This is the Greek version. There I a Syriac version, and it seems likely that in Edessa there was a pious Roman-born beggar who was known to have given up a life of luxury. His legend grew over time and the Greek (Byzantine Church) version made Rome more prominent in the telling. The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates him on 17 July. The Tridentine Calendar of Saints in the liturgical year, however, however, has reduced the importance of his feast day over time from a Simple to a Semidouble, then a Double, and finally a Simple again in 1955. Now (as of 1960) it is a Commemoration.

...and since I assume you'd like to understand what all those terms mean, I suggest you come back to this blog tomorrow.