There is a question about Ursus arctos in England, the brown bear that was most common in that part of the world: when did it disappear?

The illustrations of bears found throughout the Middle Ages show that people were quite familiar with them. There is little hard evidence of their range and dates, however. The brown bear was widespread in Europe after the last Ice Age, but estimates of when the wild population in England died out range from pre-Roman occupation to late- or even post-Medieval times. The few bones found in caves or other sites do not paint a definitive picture.

It is possible the Romans brought bears with them for the purposes of entertainment, and that some of these were released to breed and expand on the island. Some stones to mark graves from Anglo-Saxon times (420-1066 CE) have bears carved on them, and small carved bears in children's graves suggest they were considered protection for children. But were these evidence of bears in England, or just symbols brought from Northern Europe, where bears were plentiful and part of the culture?

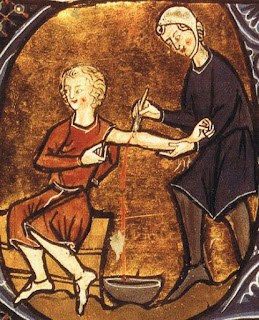

After 1066, the only certain evidence of bears in Great Britain comes from bear-baiting in London—seen in the illustration from a 14th century manuscript—and bears kept at the Tower of London as a zoo, and a medical school in Edinburgh where bones were kept.

In the 12th through 19th centuries, bear-baiting was a "sport" that involved pitting a chained bear against one or more dogs, and sometimes against other animals. In Europe, it was popular in Sweden and Great Britain. It was also common in India, Pakistan, and Mexico.

The arena for it was called a "bear garden" or "bear pit": a circular space with a high wall and raised seating outside of it. The bear would be chained by the leg or neck near one end. Henry VIII was fond of watching bear-baiting, as was Elizabeth I; she even overruled Parliament when a bill was introduced to ban bear-baiting on Sundays. Bear-baiting was eliminated by Cromwell's Puritans, but brought back after 1660. It was not long afterward, however, that people in England started to speak out against the cruelty of bear-baiting (also, the cost of importing bears was becoming prohibitive). The Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835 ended it.

Bear symbolism in the Anglo-Saxon culture, mentioned above, is probably seen no more clearly than in the greatest and best-known epic hero of Anglo-Saxon literature, the "predator of the makers of honey." You all know him, but by a different name, so I'll leave you with that riddle until tomorrow.