The earliest evidence shows that tin was being mined in at least 2150BCE, the early Bronze Age. Copper was also found there, along with some arsenic, lead, silver, and zinc, but tin mining has been the most consistent use of the mines for millennia. When a small amount of tin is added to copper, the resulting bronze is much harder than either and more useful. This made tin a more useful commodity than just using tin on its own, and a tin trade with the Mediterranean started long before even the Roman Empire. Herodotus mentions an area called the Cassiterides, the "tin islands," and Cornwall is thought to be the likeliest spot.

One of the oldest mines in Cornwall is the Ding Dong mine (the name may refer to the "head of the lode"). The picture above is a shaft at the Ding Dong. A local legend claims that the mine was visited by Joseph of Arimathea, tin trader and uncle to Jesus, who visited the mine with the young Jesus; not his only trip to Britain, since he later founded Glastonbury Abbey, etc. (There is, of course, no evidence, but that's what legends are.)

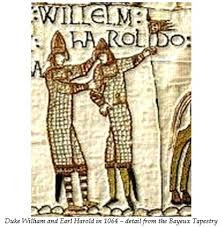

Curiously, Domesday Book doesn't mention Cornwall tin, but Henry II acknowledged it when he granted to Dartmoor, another mining location,

all the diggers and buyers of black tin, and all the smelters of tin, and traders of tin in the first smelting shall have the just and ancient customs and liberties established in Devon and Cornwall.

This indicates that Cornwall mining was "ancient" as of Henry's reign. Henry's son John granted a charter for the miners' rights, establishing stannaries that allowed the tin-mining community to administer its own laws, etc.

The mines produced an enormous amount: 650 tons in 1337, falling to "only" 250 tons during the Black Death, but rising to 800 tons by 1400.

Demand for tin decreased in the 20th century. Increased recycling efforts, as well as the use of aluminum for containers and the development of protective polymer lacquers to coat food containers hastened the closing of tin mines as unprofitable. One of the last tin mines in Cornwall to close was the South Crofty mine in 1998, Europe's last tin mine.

Fear not for Cornwall mining, however! The 21st century is finding reasons to re-open defunct Cornish mines for a substance as important to our time as tin was to the Bronze Age: lithium, an element vital to our battery-operated world. (Here is a link to National Geographic article.)

Going back to the Middle Ages, however, I want to talk about another substance, made with tin, that was so associated with daily use in the Middle Ages that a 19th century revival of interest in the Middle Ages made this substance much in demand. Check back tomorrow and we'll learn more about the lovely, useful, and toxic pewter.