The inspiration for the Waldensians was when Waldes heard a troubadour sing about St. Alexius of Rome, a man whose situation was similar to that of Waldes. Both were well-to-do, Alexius even more so.

The story goes that Alexius was born into one of the most prominent families in Rome in the 4th century, the son of Euphemianus, a Christian. The family was liberal with its wealth, with many offerings to the poor. Alexius grew up well-educated, steeped in a tradition of generosity, wanting for nothing; in turn, he was the pride and joy of his family.

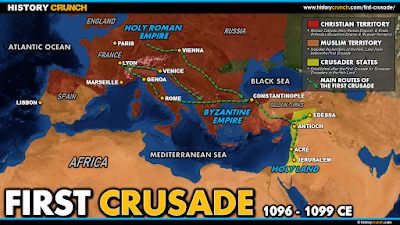

By and by, his parents arranged a marriage to a young woman of great virtue and wealth. The wedding was grand and the wedding feast lavish. Later that day, however, Alexius was overcome with the urge to give up his wealth, his home, and his new bride. He went to her, giving her to take as tokens of his love jewels and riches. He then went to his own room, changed out of his sumptuous wedding garb, and left the household secretly. He went straight to the harbor and took the first ship to Edessa in Syria.

His disappearance caused his parents to send searchers high and low for him, but of course they never found him. He was living in voluntary poverty in Edessa, giving away all he had and clothing himself in rags. He fasted, slept for a few hours in the vestibule of a church dedicated to Mary, prayed all night, and spent an hour each day begging for alms. This style of living altered him so much that his friends and family would not recognize him. In fact, his parents' servants traveled as far as Edessa in search of the young man, and he was able to beg for alms from them without them recognizing him.

One day, the curate of the church where he resided heard a voice coming from the statue of Mary saying that the poor man in the vestibule was a servant of the Almighty whose prayers were very agreeable to God. The curate spread the word of this, and Alexius began to be visited and praised. This was the opposite of the humility he sought, and so he determined to leave Edessa. The first ship he took went to Rome. He was inspired by God to go to his father's house where, upon encountering his father, he said “Lord, for the sake of Christ, have compassion on a poor pilgrim, and give me a corner of your palace to live in.” Euphemianus, a pious man, took in the unrecognized son, instructing his servants to give him a place to stay and daily food. He was given a cubby under the stairs, where he stayed for 17 years, except for visits to church. Seeing his parents and bride still grieving for him was torturous, but he determined to remain anonymous, lest he be unwillingly returned to a life of luxury and leisure. When he felt his death was near, he went to Mass and Communion, went back home and wrote a brief biography of his years since his wedding night, folded it and held it in his hand. He then died peacefully.

Meanwhile, at Mass attended by Euphemianus and Emperor Honorius(384 - 423), and celebrated by

Pope Innocent I (d.417), a voice was heard proclaiming that the servant of God at the house of Euphemianus was dead. The Pope and the Emperor accompanied Euphemianus to his house where they found the holy man dead, the paper held tightly in his hand until by praying the Pope was able to take it from him. They were all astonished at the reading. The house of Euphemianus was turned into the first church dedicated to Alexius.

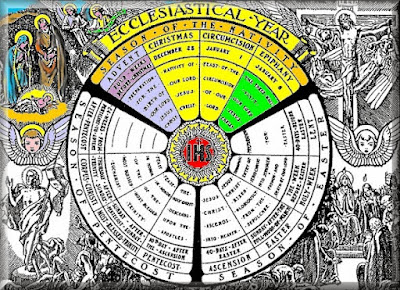

Of course, as "detailed" as a story of a saint's life may be from 1600 years ago, we have to cast some doubt on it. There are several versions of this story. This is the Greek version. There I a Syriac version, and it seems likely that in Edessa there was a pious Roman-born beggar who was known to have given up a life of luxury. His legend grew over time and the Greek (Byzantine Church) version made Rome more prominent in the telling. The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates him on 17 July. The Tridentine Calendar of Saints in the liturgical year, however, however, has reduced the importance of his feast day over time from a Simple to a Semidouble, then a Double, and finally a Simple again in 1955. Now (as of 1960) it is a Commemoration.

...and since I assume you'd like to understand what all those terms mean, I suggest you come back to this blog tomorrow.