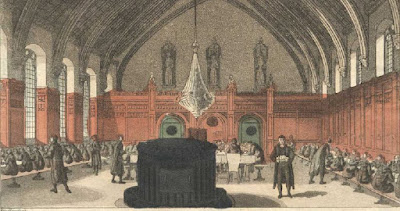

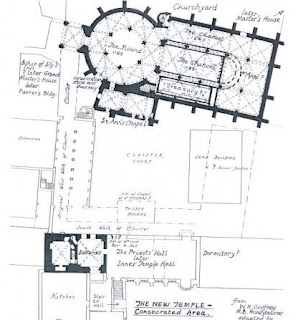

The Hospitallers were not so large and expanding that they needed the space, and so it is likely that they used it as income, renting it as living/work space. Tradition says that there were lawyers living there in the 1340s, but a formal educational institution cannot be proved...although there is a recorded incident in 1339 when "a man was killed in the Temple by a servant of the apprentices of the king’s court, which suggests that they may already have formed a community there." [link] In 1388, both "Inner Temple" and "Middle Temple" are specifically named in documents. The picture above is a mezzotint from 1826 showing dinner in the hall of one of the Temples.

Another incident involving the Temple is confirmed during the Peasants Revolt in 1381 (most recently summarized here, but also found in much more detail throughout this blog). The rebels tore down the Inner Temple hall and several houses before burning down the Savoy. When the building was torn down in 1868, it was noted that the roof used 14th century construction methods that would have been unavailable to the Templars.

Wat Tyler's followers supposedly were happy to destroy all the legal records they could find. It is true that no records exist from the 1300s, but neither do any exist from the 1400s. No formal records exist for any of the Inns of Court prior to 1500, except for Lincoln's Inn whose Black Books begin in 1422. The 1500s saw significant expansion of the Inns and their population and influence on English law.

Our brief history of the Temple after it was taken from the Templars is done, but what of the Hospitallers? When did they give it up? What happened to them? Let's look at that tomorrow.