Somewhere along the way, folk learned that the galls could be used for something other than a wasp hatchery. Pliny makes a vague reference to oak gall ink. The typical way to make ink from oak galls was to crush the galls, add water, and boil the concoction; sprinkling in some iron sulfate turns the mixture black.

Too much iron could be problematic, however. It turned the ink corrosive, and too much iron could destroy (over time) the document for which it was used. But oak gall ink was the popular ink for 1400 years, and some of the oldest manuscripts have easily survived. The Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest Bible known (from c.325 CE), used oak gall ink.

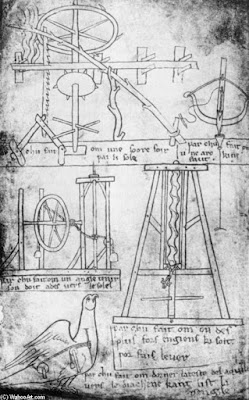

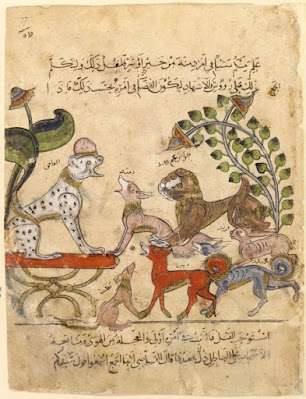

Oak gall ink, sometimes called iron gall ink, was prevalent for at least 1400 years. The majority of manuscripts from the Middle Ages were made with oak gall ink, which dries to a light brown. Great Britain and France mandated oak gall ink for legal records. The popularity extended to the Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci used oak gall ink. Even later, the U.S. Postal Service had its own prescribed version of oak gall ink at their branches.

One of the reasons the popularity of iron gall ink faded was the rise of the fountain pen. The ink was suitable for dip pens, but dip pens hold only a little ink on the tip, and the writer had to constantly re-dip the pen point into the ink and be careful not to splatter ink drops while traveling from the ink bottle to the page. Fountain pens were developed that stored more ink and released it slowly, as the ink was drawn from the tip. The fountain pen uses capillary action to raw the ink along a thin barrel, and the iron in iron gall ink could create deposits in the barrel that would impede the smooth flow of the ink. The development of other ink formulations made fountain pens more useful.

Oak gall ink is still manufactured for those few who want it. The U.S. Postal Service no longer uses it. But that suggests a direction for tomorrow: how did mail service work in the Middle Ages?