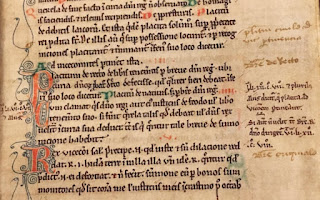

The phrases "feudal system" and "feudalism" were not used in the Middle Ages. They were coined in the 1700s by scholars describing economic systems. The Medieval Latin

feodum (whose precise origin is unknown), it was used to refer to a grant of land one xchange for a service. Documents originally used the Latin

beneficium, but for some reason that term started being replaced with

feodum by the year 1000.

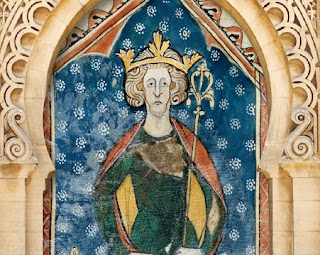

As societies grew more populated and government became less centralized, the feudal system enabled better management of land by "outsourcing" to trusted people. The trustee, or vassal, would pledge to fight for the lord who granted the land, using revenue from the land to furnish military equipment. Feudal customs varied from country to country, but the pledge of military support was common.

The primary vassal didn't work the land himself. A hierarchy evolved over time. Here are several positions of the economic/social strata that existed in English feudalism.

Lord Paramount, or Territorial Lord: the highest role in feudalism; the person who had no loyalty to anyone higher. In England, the king.

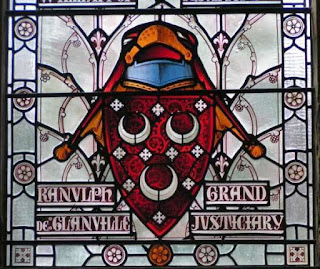

Tenant-in-chief: the person who holds his land from the king.

Mesne lord: a person who had vassals under him, but was in turn a vassal of a higher lord but not of the king.

Landed gentry/Gentleman: someone whose grant of land was sufficient to support him in comfort; this person might use the term esquire, but that was a courtesy title and conferred no special status.

Franklins & Yeomen: free men (not tied to the land by contract); they might be thought of as a middle class. Yeomen often were guards for the mesne lord or tenant-in-chief.

Free tenant/Husbandman: peasant farmers who worked the land and paid rent (and a percentage of goods) to the landholder.

Serf/Villein: peasant farmers who were essentially indentured to the landowner and legally forbidden to seek employment elsewhere.

So, if you had a choice to be a free tenant or an unfree serf, which do you think you would choose? There are some records from medieval England that may just shed some light on that topic, which I'll share with you tomorrow.