10 March 2022

Alamut Castle

09 March 2022

The Order of Assassins

With that out of the way, we can discuss their origin more calmly. They were originally called the Nizari Isma'ili State, founded by Hassan i-Sabbah. Sabbah (c.1050 - 12 June 1124) was a Twelver Shia, called thus (in English, anyway) because they believed in twelve divinely ordained imams who are the spiritual successors to Muhammad.

Sabbah was strongly Twelver, but later in life embraced the Isma'ili doctrine. The followers of Isma'ilis believed that Isma'il ibn Jafar was the proper spiritual successor to Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq; other Twelver Shia believed Isma'il's younger brother, Musa al-Kadhim, was the true Imam. Sabbah further made "different choices" in Cairo when he gave his support to Nizar, the son of Isma'ili Imam-Caliph al-Mustanṣir, as the next Imam. Sabbah was jailed by the chief of the army, but the collapse of one of the jail's minarets was taken as a sign to get rid of him: he was therefore deported. He wound up in Isfahan in 1081.

Sabbah decided he needed a stronghold where he could found the Nizar Isma'ili State, maintain his own safety, instruct others in his beliefs, and from which he could conduct his mission to spread the word of his specific beliefs. In 1090 he and his followers captured Alamut Castle, the first and greatest of the Nizari Isma'ili fortresses. From here he used his Order of Assassins to covertly eliminate leaders—first Muslim, later Christian as well—who stood in the way of spreading his version of Islam.

The way he conquered Alamut Castle, and the castle itself, deserve more than a passing glance. I'll tell you about it tomorrow.

08 March 2022

Benjamin of Tudela

I wrote a post about Benjamin of Tudela (1130-1173) back in 2012, but there is a lot more to him. His Masa'ot Binyamin (Travels of Benjamin) details eight years of traveling, and gives western scholar greater insight than we otherwise would have into Jewish (and other) inhabitants east of the Mediterranean. He frequently notes the mutual respect found in mixed communities of Jews and Muslims.

Here is a sample from early in his book (parasang is a Persian unit of distance of about 4 miles):

From Montpellier it is four parasangs to Lunel, in which there is a congregation of Israelites, who study the Law day and night. Here lived Rabbenu Meshullam the great rabbi, since deceased, and his five sons, who are wise, great and wealthy, namely: R. Joseph, R. Isaac, R. Jacob, R. Aaron, and R. Asher, the recluse, who dwells apart from the world; he pores over his books day and night, fasts periodically and abstains from all meat. He is a great scholar of the Talmud. At Lunel live also their brother-in-law R. Moses, the chief rabbi, R. Samuel the elder, R. Ulsarnu, R. Solomon Hacohen, and R. Judah the Physician, the son of Tibbon, the Sephardi. The students that come from distant lands to learn the Law are taught, boarded, lodged and clothed by the congregation, so long as they attend the house of study. The community has wise, understanding and saintly men of great benevolence, who lend a helping hand to all their brethren both far and near. The congregation consists of about 300 Jews—may the Lord preserve them.

All in all, he visited about 300 cities and many Jewish communities. His book contains one of the earliest descriptions of the ancient site of Nineveh. He also writes about the Al-Hashishin, the order of assassins who lived in the mountains of Persia and Syria. Maybe it would be interesting to look into them a little more tomorrow.

You can read his book at Project Gutenberg.

07 March 2022

Druze

When Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah became caliph at the age of 11, no one could have predicted what the future would bring, especially the point at which he declared himself the earthly incarnation of God. To be more accurate, he was declared thus by Hamza ibn ‘Alī ibn Aḥmad, who was preaching a philosophy that was a blend of Isma'ilism (a subset of Islam), Gnosticism, Christianity, Neoplatonism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Pythagoreanism, and any other idea he liked. It was Hamza who initially "recognized" Al-Hakim as God Incarnate.

This was unacceptable to the majority of Shi'a Muslims in the area, but a small group decided to embrace this announcement. Among them was Muhammad bin Ismail Nashtakin ad-Darazi. When he discovered the new religion, he began preaching on its behalf, and started gaining followers. His growing mass of followers motivated him to start calling himself "The Sword of Faith." This nickname, however, was a sign of a major Druze sin: arrogance. (Consider the irony of "arrogance" being a sin in a religion founded when someone claimed to be God Incarnate.) This led to a clash with Al-Hakim, who said "Faith does not need a sword to aid it." Unfortunately for ad-Darazi, he did not take the hint and kept annoying the "incarnation of God," and he was ultimately labeled a heretic and executed in 1018.

This brings us to the second irony: the Druze religion is named after the early preacher who was executed for being a heretic. To be fair, there are other theories: that it derives from Arabic dārisah ("she who studies") or the Persian Darazo ("bliss"). In early texts, they refer to themselves as muwaḥḥidūn ("unitarian"). One of the earliest references to "Druze" comes from Benjamin of Tudela, who encountered them in Lebanon in 1165.

When Al-Hakim disappeared mysteriously in 1021, his successor and son persecuted Druze adherents. This drove them underground. Druze are scattered worldwide, but are mostly in Lebanon, Syria, and Israel. They frequently will publicly adopt other religions but practice Druze secretly. Druze in modern Israel number about 150,000, and are the only Arab group conscripted into the Israel Defense Forces; they sided with Israel in the 1948 war. When the Israel Knesset in 2018 established a law that Israel was a Jewish state, the Druze were appalled, claiming it made them second-class citizens in a country where they had shown undying loyalty.

But by and large, the Druze try to get along with everyone. Even in 1165, Benjamin Tudela wrote that they "loved the Jews."And speaking of Benjamin of Tudela: interesting guy; a Spanish Jew who traveled the known world and wrote it all down. We'll look into his travels tomorrow.

06 March 2022

A Tale of Two Caliphs

Al-Hakim (pictured here) was born in Egypt, and succeeded his father at the age of eleven. Rumors that he was the offspring of his father and a Christian consort—and the desire to eliminate the "taint" of Christianity, might have been the motive for destroying the hospital, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, as well as a reported 3000 other buildings in Jerusalem.

Of course, becoming caliph at eleven could also instill the notion that you can do whatever you want. Not only that, a religion sprang up around him. He was considered God made flesh in the burgeoning Druze religion.

To be fair, he became kinder in is later years—not too much later, since he lived only until 35. He embraced asceticism and frequently took to meditation. Then, on a February evening in 1021, the man who had been called "the mad caliph" set out on a journey but never arrived at his destination. A search found his donkey and bloodstained garments. No explanation has been found, and there is no evidence to support the rumor that his sister had a hand in it. She assumed temporary control of the court, pushed out Al-Hakim's chosen successor, and pushed for Al-Hakim's son to succeed as caliph.

That son was Al-Zahir li-i'zaz Din Allah (20 June 1005-13 June 1036). One of his changes was to delegate more responsibility to court officials, which started a trend that would make the caliphs less and less powerful over the years. Al-Zahir allowed the rebuilding of the aforementioned hospital in Jerusalem. He also tried to eliminate the Druze religion. It didn't work, and the Druze religion—little known, but millions strong even to this day—might as well be the next topic.

05 March 2022

Jerusalem Hospital

The name Muristan appears much earlier, due to a hospital built by Abbot Probus about 600CE at the orders of Pope Gregory I. This was built to treat ill pilgrims who made the trek to the Holy Land. We should note that this is long before any Crusades to "liberate"—actually, "conquer" would be more accurate—the Holy Land. Muslims, Jews, and Christians all managed to coexist through many periods of time—though not always, as you'll see. About 614CE, a Persian army invaded, killing Christians and destroying their structures, including the hospital.

Jump ahead 200 years, and Charlemagne in 800 (after being crowned Holy Roman Emperor) revived Probus' hospital and expanded it, adding a library (Charlemagne was a great supporter of learning, as you can read about in a 2013 post.) Unfortunately, in 1009, Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (sometimes called "the mad caliph" or the "Nero of Islam") destroyed the hospital as well as thousands of other buildings.

Which brings us up to 1023, when merchants from Amalfi and Salerno requested of Caliph Ali az-Zahir the opportunity to rebuild the hospital. It was granted, which brings us back to the Hospitallers several decades later, and the incarnations of the hospital are complete.

But there is a postscript. During excavations for a restaurant, he original structure was discovered and explored between 2000 and 2013 by the Israel Antiquities Authority. At its heyday, between 1099 and 1291, it was 150,000 square feet and could accommodate up to 2000 patients. Evidence exists that it served kosher food to Jewish patients, and that it also housed orphans, many of whom joined the Hospitallers. Bones from horses and camels found suggest it was also used as a stable. Part of a vaulted roof will be incorporated into the restaurant, and so the first home of the Hospitallers lives on in some small fashion.

But what about the "mad caliph" who destroyed a hospital and the kind caliph who let one be built? Would you believe they were father and son? Sometimes the apple does fall far from the tree, which we'll go into tomorrow.

04 March 2022

What About the Hospitallers?

Pope Clement V, who approved the order to arrest all the Templars, had earlier told them to merge with the Hospitallers, since it didn't seem necessary to him to have two groups who were performing the same function: guarding/assisting people traveling to the Holy Land. Who were the Hospitallers?

In 1023, a hospital was built in Jerusalem on the site of the Benedictine monastery of St. John the Baptist, to care for sick and injured pilgrims. When Jerusalem was taken over by the First Crusade, some Crusaders formed the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem—colloquially known as the Hospitallers—to support the hospital. A papal charter charged them with the care and defense of folk in the Holy Land. This evolved from caring for people to providing military escorts and then to fighting in wars for Christendom.

Once Jerusalem was retaken by Muslims, the Hospitallers made their home base in Rhodes. Even later they had to relocate to Malta. They spread far and wide, establishing a presence in England and Normandy by 1200. They spread to Ireland, to Hungary, to Russia, and of course around the Mediterranean. They even made a presence in North America: they briefly colonized four Caribbean Islands—including Saint Martin and Saint Barts—which they gave to France in the 1660s.

The Knights had a bad time during the Protestant Reformation of the 1500s when several large Northern European sections of the order broke from their Roman Catholic roots. The French Revolution abolished the Order in France along with abolishing feudalism and tithes.

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, more commonly known now as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, is considered the successor to the Hospitallers. The Order headquartered in Rome as of 1834; they performed extensive hospital work during the two World Wars.

About that original hospital: it was excavated between 2000 and 2013, and was a replacement for an even earlier hospital. I'll talk about that next time.

03 March 2022

The Temple Inn

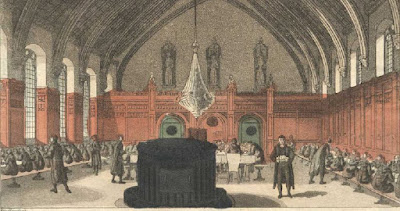

The Hospitallers were not so large and expanding that they needed the space, and so it is likely that they used it as income, renting it as living/work space. Tradition says that there were lawyers living there in the 1340s, but a formal educational institution cannot be proved...although there is a recorded incident in 1339 when "a man was killed in the Temple by a servant of the apprentices of the king’s court, which suggests that they may already have formed a community there." [link] In 1388, both "Inner Temple" and "Middle Temple" are specifically named in documents. The picture above is a mezzotint from 1826 showing dinner in the hall of one of the Temples.

Another incident involving the Temple is confirmed during the Peasants Revolt in 1381 (most recently summarized here, but also found in much more detail throughout this blog). The rebels tore down the Inner Temple hall and several houses before burning down the Savoy. When the building was torn down in 1868, it was noted that the roof used 14th century construction methods that would have been unavailable to the Templars.

Wat Tyler's followers supposedly were happy to destroy all the legal records they could find. It is true that no records exist from the 1300s, but neither do any exist from the 1400s. No formal records exist for any of the Inns of Court prior to 1500, except for Lincoln's Inn whose Black Books begin in 1422. The 1500s saw significant expansion of the Inns and their population and influence on English law.

Our brief history of the Temple after it was taken from the Templars is done, but what of the Hospitallers? When did they give it up? What happened to them? Let's look at that tomorrow.

02 March 2022

The Inner Temple

Founded in 1119CE and devoted to the emancipation of the Holy Land, their international presence made them popular as safe escorts and money-handling institutions. They maintained almost a thousand locations across all of Europe and the Near East, and were a popular recipient of donations.

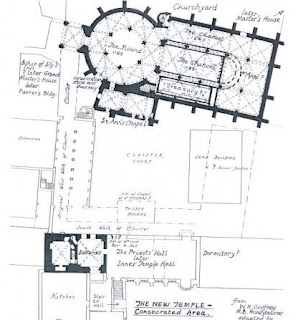

During the reign of Henry II, the Knights built their set of buildings on the banks of the Thames, laying down a new street that gave access to them. They called this New Street, but today it is known as Chancery Lane. It was obviously not a law school at the time, although lawyers were there as advisors for the Knights.

The Knights ran into trouble when, on 13 Friday 1307, France ordered the arrest of all Templars. (If the date makes you wonder, go here.) King Philip IV needed money after his wars with England, and relied on rumors of impropriety to convince Pope Clement V to outlaw them, allowing Philip to confiscate their wealth. England did not have any beef with the Knights, but their order faded quickly and was officially dissolved in 1312. The buildings in London were given to the Knights Hospitaller, an order whose activities were similar to the Templars.

You can read more about Clement's decision here, and why he was so aligned with Philip to go along with him here. I want to talk a little more about the Inner Temple and what happened to it later. See you next time.

01 March 2022

The Inns of Court

In the early Middle Ages, law was taught by the clergy, but Pope Honorius III in 1218 forbade the clergy to practice civil law. Then, in 1234, Henry III forbade law schools within the London city limits. Laymen interested in teaching law moved outside London and looked for buildings or collections of buildings to buy or rent, and the guilds in which they worked evolved into the Inns of Court. Four Inns exist: The Honorable Societies of Lincoln's Inn, the Inner Temple, the Middle Temple, and Gray's Inn. They truly were inns, because students lived as well as learned there. They are all near each other.

Although Lincoln's Inn claims the earliest records going back to 1422 (incidentally, the picture above is the Lincoln's Inn library) we know that lawyers lived in the Temple as early as 1320, though not as teachers. In 1337 the place was divided into the Inner Temple, and the Middle Temple (as distinct from an Outer Temple that existed). By 1388 they were two distinct groups. In 1620, a meeting of senior judges decreed that all four were considered equal in order of precedence, regardless of when they may have been founded.

Like the seven subjects of the University curriculum, law students were expected to spend seven years learning the law, mostly by attending court and asking questions afterward. Their experience included dining communally with practicing barristers for networking and additional knowledge. It wasn't until the mid-18th century that common law became. subject for study in universities.

The Inns of Court recognized three levels: student (learning law), barrister (practicing law), and master of the bench (called "bencher"). Benchers were senior members of the Inns, and could be appointed by existing benchers when still a barrister. An appointed High Court Judge was automatically a bencher. Benchers were the governing body of their respective Inn. Their duties were to admit students, "graduate" students, and appoint other benchers. One bencher was appointed Treasurer for a term on one year.

But I know the question nagging at you is "Why were they called the Inner and Middle Temple?" You either know why, and are wondering if I'll address the subject, or don't know why, and are hoping I'll answer your question. Good news for both: I'll answer the question tomorrow.

If you are curious what the seven subjects were, you can find a list in this post, or you can learn more about them (and much more) here.

28 February 2022

Sharia Law in the Middle Ages

Sharia drew distinctions between men and women, Muslims and non-Muslims, free people and slaves. In many situations a woman's worth was considered half that of a man. A husband's financial obligations, however, gave wives some protection against divorce and following poverty. Women could be plaintiffs or defendants in Sharia courts, without having to rely on a male representative. A Muslim man could marry a Christian or Jewish woman, and she was allowed to worship at her own church/synagogue.

Non-Muslims were considered dhimmi, which literally means "protected person." This status was given to Jews and Christians, who were "People of the Book" (the book being the shared Old Testament). They had certain privileges—although in many cases "permissions" might be more accurate—and certain obligations. Dhimmi paid the jizya, a tax on non-Muslims residing in Muslim-controlled countries. If you were not a dhimmi but were, say, a pagan, you were not required to pay the jizya; you were required to convert to Islam or face death. (Later, dhimmi status was applied to pagans and many more types, such as Zoroastrians, Sikhs, Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists.

This is obviously the briefest of looks at Sharia law and how it might affect folk in the Middle Ages. I think it's time to head north. Tomorrow I'll talk about the above-mentioned Inns of Court.

27 February 2022

The Iberian Melting Pot

"Mozarab" is likely from the Arabic musta 'rib, which is most easily translated as "to make oneself similar to Arab." Medieval writers used the term "Mozarabic" to refer to Christians living in the Iberian Peninsula which had been steeped in Arabic and Islamic culture. The earliest example we have is from 1026CE, in a land dispute between monks of San Ciprian de Valdesalce and three muzaraves de rex tiraceros (royal silk workers). By 1085 Mozarab was more common, being used to mean Christians who lived under Muslim rule, adopting their customs and language.

The point is that Arabs, Jews, Christians, and Mozarabs were able to coexist on the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. The multilingualism among many individuals that resulted from this coexistence made the location ideal for scholars from all over to come to learn from sources in other languages. The Archbishop establishing the Toledo School of Translators was an original idea, but not a surprising one, considering the resources at hand.

It would be unfair, however, to neglect telling you that some Christian scholars traveled to Iberia to learn to read the Koran well enough to be able to write polemics against it. In turn, as Roman law became increasingly irrelevant in Iberia, the non-Muslims had to deal with Sharia law. But that's a topic for next time.

26 February 2022

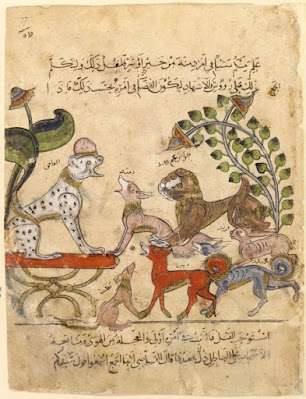

A Book of Fables

The title refers to two of its characters who are jackals, the steady Kalīla and the ambitious Dimna. They are door wardens for the king, who is a lion. Oddly enough, Kalīla and Dimna only appear in the first of the 15 stories contained in the collection.

Several of the stories include a king, and their subject matter is usually about the relationship and duty of a king toward his subjects. The introduction to the book claims that it was written for the king of India. It was then called the Panchatantra. When the king of Persia, Khosrow I, heard of the book, he sent his physician to India to make a copy in Pahlavi (Middle Persian).

Copying was not allowed by the king of India, but the physician, Borzuya, was allowed to read it. He read a story each day, and then at night wrote in a journal what he remembered. In this way he brought the fables westward. The Arabic author and translator Ibn al-Muqaffa (died c.756) translated it into Arabic as Kalīla wa-Dimna. It became the first Arabic literary classic. Its popularity led to the publication of a German version by Gutenberg. Today copies can be found in over 100 languages.

The frequent theme of a king's relationship with his subjects places this collection not only into the genre of fables but also into the genre of "Mirrors for Princes," guides to teach proper conduct when one has authority and responsibility.

One more foray into the realm of cultural and linguistic melting pots: next time, we look at Mozarabic culture.

25 February 2022

Toledo School and Language

The Iberian Peninsula at the time contained several different kingdoms. The Toledo School of Translators was in the southern part of Castile. Navarre and Aragon were eastward, and the Catalan Counties further east. Galicia and Leon were westward, and also Portugal (much smaller than it is today). Southward was all Muslim-held. All these territories had their own dialects; not only was there no "Spain," there was no "Spanish." Into this situation stepped King Alfonso X of Castile.

Alfonso (1221-1284CE) was King of Castile, León, and Galicia. His court was a melting pot of Jews, Muslims, and Christians, and he encouraged the translation of scholarly works from Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin into the Castilian vernacular. He wanted more works put into a language that was llanos de entender ("easy to understand") and would therefore reach a wider audience, not just the highly educated. They used a revised version of Castilian that would become the foundation of Spanish.

The method of translation changed as well as the target language. In the first phase of the school, a native speaker would read aloud the work to a translator who would dictate Latin to a scribe. Under Alfonso, a multi-lingual translator would translate from the original language to Castilian, which he would dictate to a scribe. The resulting text would be checked by editors for accuracy. Sometimes, Alfonso himself would proofread the text.

Alfonso of course dealt with other affairs besides scholarship. He had a civil war, for instance, but it's nice to focus on something other than politics in a king's reign. For instance, he organized about 3000 sheep holders into the Mesta to ensure a coordinated supply of wool. Someday I may return to Alfonso, the Mesta, and why it and his other policies were economically disastrous for him. For tomorrow I want to look at the very first translation in Castilian to come out of Alfonso's revised school, a book of fables.

24 February 2022

The Toledo School of Translators

The archbishop assembled a team that included Jewish scholars, Madrasah teachers, Cluniac monks, and Mozarabic Toledans.

The goal was not just to make Arabic learning available to the Latin-speaking west. Arabic texts were translated also into Hebrew and Ladino (Judaeo-Spanish). Examples are works by Maimonides, Ibn Khaldun (considered the originator of studies that would evolve into sociology and economics), and the physician Constantine the African.

The school was well-organized, and as a result we are aware of many of the translators who worked there. Gerard of Cremona was not the only noteworthy translator. John of Seville (fl.1133-53) was one of the chief translators into Castilian, working closely with Dominicus Gundissalinus, the first appointed director of the school.

The importance of Toledo for Western European scholarship cannot be underestimated. The University of Paris was the seat of the Condemnations of Paris: between 1210 and 1277, they were enacted to restrict teaching that were considered heretical. Without Toledo, who knows how long it might have taken for Europe to gain access to so much knowledge?

The school had two chief periods of activity. Tomorrow I'll talk about the second, and the importance of Castilian.