He was born in 1225 in the town of Aquino. His father was Count Landulph of Aquino, his mother Countess Theodora of Teano; he was related to the kings of Aragon, Castile, and France, as well as to Emperors Henry VI and Frederick II. A biography written a generation after he died claims that a holy hermit predicted to a pregnant Theodora that her child would become unequalled in learning and sanctity.

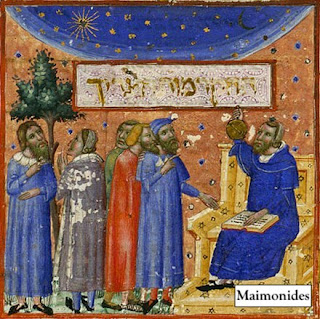

His education began at the typical age of five, with the Benedictines of Monte Cassino (his father's brother Sinibald was the abbot there from 1227-1236). Some time between 1236 and 1239 he was sent to a university at Naples where he would have first learned about Aristotle, Averroes, and Maimonides. Here he also came into contact with a Dominican preacher. The Dominicans had been founded 30 years earlier and were actively recruiting.

When he was 19 years old, Thomas announced that he wished to join the Dominicans, which displeased his "Benedictine-oriented" family. It displeased them so much that, while Thomas was traveling to Rome on his way to Paris to get away from the family's influence, his brothers (at his mother's request) kidnapped him. He was forced to stay in his parents' castle for almost a year, spending the time tutoring his sisters.

Attempts to dissuade him from the Dominicans became more desperate. His brothers sent a prostitute to seduce him. He fought her off with a burning log, then fell into a mystical trance and had a vision of two angels granting him perfect chastity. (They also gave him a "girdle of chastity" that now resides in Turin.) His mother, seeing that he would not change his mind, and not wanting to endure the embarrassment of allowing her son to join the Dominicans, she arranged for him to escape his home in 1244. He went to the University of Paris where he probably studied under Albertus Magnus. Because Thomas was quiet, his fellow students ridiculed him, but Albertus is supposed to have told them "You call him the dumb ox, but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world."

In 1256 he was appointed regent master in theology at Paris and began writing the first of his many theological works, Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem ("Against Those Who Assail the Worship of God and Religion"), defending the mendicant orders.

His reputation as a theologian and teacher/preacher grew so much that he was granted the Archbishopric of Naples in 1265 by Pope Clement IV, but he turned it down. In the yard that followed he would have the time to write one of his greatest works, the Summa Theologica.

And this is where we come back to the comparison with Maimonides: despite the groundbreaking nature of his writing, which became foundational for much of what followed, he was not without his detractors. Some of his conclusions clashed with accepted thought from previous religious writers. To be able to discuss that, we should look at two other philosophers: Aristotle and Averroes. Stay tuned.