[Mindful of the tragedy at Notre Dame of Paris on 15 April, 2015, I re-present this post from 2012.]

In the post on the Las Huelgas Codex I mentioned that many of the pieces in the codex were new to scholars, but some were familiar. Where else had they been seen?

The collection of recorded polyphonic music produced by composers working at Notre Dame Cathedral from c.1160-c.1250 is referred to as the Notre Dame School of Polyphony. A majority of medieval polyphonic music up to this time was committed to parchment by the Notre Dame School.

This does not man, sadly, that we can set a manuscript in front of a modern musician and have the notes played as they were intended to be heard. Differences in musical notation and rhythm make it close to impossible to know precisely how these pieces were performed centuries ago. For us to make an attempt is only feasible because of analyses of music written by a handful of people. Franco of Cologne was one, John of Garland another (best estimates are that he was keeper of a bookshop in Paris who edited two treatises on music), and the later writing of the industrious student known only as Anonymous IV.*

Thanks to Anonymous IV, we have contemporary definitions of what is meant by organum (a plainchant melody with one voice added to enhance harmony), discantus ("singing apart"; a liturgical style of organum with a tenor plainchant and a second voice that moves in "contrary motion"), the rules for consonance and dissonance, and other terms and rules of polyphony.

One "ironic" result of the writing of Anonymous IV is that. through him, we know the names of two composers who would otherwise have been lost to obscurity. He writes about Léonin and Pérotin with such detail and feeling that, although Anonymous would have lived several decades after they lived and composed, they were presumably so famous that their reputations lived on in the school. Léonin and Pérotin are some of the earliest names of artists that we can actually link to their works.

As much as we have been given by the treatise of Anonymous IV, his own identity and details of his life are unknown. Two partial copies of his work survive at Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk, England; one is from the 13th century, and one from the 14th. Clearly, his work was considered important enough to copy and preserve—but not his name. He was likely an English student who was at Notre Dame for a time in the late 13th century. Thanks to his interests, we understand more about the development of medieval polyphonic music than we otherwise would have.

*His name is the inspiration for a modern female a capella group.

In the post on the Las Huelgas Codex I mentioned that many of the pieces in the codex were new to scholars, but some were familiar. Where else had they been seen?

|

| Notre Dame Cathedral |

This does not man, sadly, that we can set a manuscript in front of a modern musician and have the notes played as they were intended to be heard. Differences in musical notation and rhythm make it close to impossible to know precisely how these pieces were performed centuries ago. For us to make an attempt is only feasible because of analyses of music written by a handful of people. Franco of Cologne was one, John of Garland another (best estimates are that he was keeper of a bookshop in Paris who edited two treatises on music), and the later writing of the industrious student known only as Anonymous IV.*

|

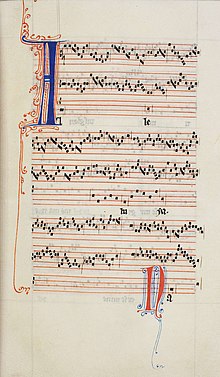

| The "Alleluia nativitatis" by Pérotin |

One "ironic" result of the writing of Anonymous IV is that. through him, we know the names of two composers who would otherwise have been lost to obscurity. He writes about Léonin and Pérotin with such detail and feeling that, although Anonymous would have lived several decades after they lived and composed, they were presumably so famous that their reputations lived on in the school. Léonin and Pérotin are some of the earliest names of artists that we can actually link to their works.

As much as we have been given by the treatise of Anonymous IV, his own identity and details of his life are unknown. Two partial copies of his work survive at Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk, England; one is from the 13th century, and one from the 14th. Clearly, his work was considered important enough to copy and preserve—but not his name. He was likely an English student who was at Notre Dame for a time in the late 13th century. Thanks to his interests, we understand more about the development of medieval polyphonic music than we otherwise would have.

*His name is the inspiration for a modern female a capella group.