There is a 20th century art historian who has appeared in two posts because of his eye-opening contributions to the field in the 1940s:

here where he explained multiple renaissances, and

here where he pinpointed the birth of gothic architecture

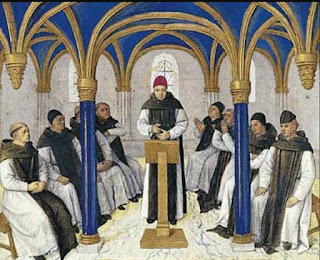

and the motivating factor behind it. (I recommend you check those links before you read further.) He followed those in 1951 with a lecture called "Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism."

He noted that gothic architecture originated and flourished in the "100-mile zone around Paris" and was contemporaneous with the growth and spread of scholasticism. This would have been interesting enough on its own as an observation, but he went further, insisting there was:

A connection between Gothic art and Scholasticism which is more concrete than a mere "parallelism"...the connection which I have in mind is a genuine cause-and-effect relation.

We can extrapolate some connections ourselves without looking further into Panofsky: the architect and the scholastic were two of the most educated people in the community. Both, in their own way, were blending the religious (a site for worship, church doctrine) with something more "grounded" (a complex building, logical reasoning).

Panofsky also sees the scholastic trend toward categorization and chapter/sub-chapter organization of thought in the arch>smaller arch layering of the typical Gothic elevation (see the illustration). Likewise, he sees the desire to match scholastic clarification in the large windows that allowed more light than the previous Romanesque style, and the intellectual desire for getting at the "unvarnished truth" in the exposed buttresses.

He concludes with one more observation:

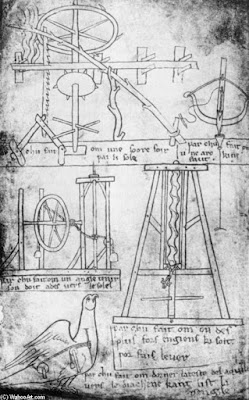

...which shows that at least some of the French thirteenth-century architects did think and act in strictly Scholastic terms. In Villard de Honnecourt’s “Album” there is to be found the groundplan of an “ideal” chevet* which he and another master, Pierre de Corbie, had devised, according to the slightly later inscription, inter se disputando. Here, then, we have two High Gothic architects discussing a quaestio, and a third one referring to this discussion by the specifically Scholastic term disputare instead of colloqui, deliberare, or the like. And what is the result of this disputatio? A chevet which combines, as it were, all possible Sics with all possible Nons.

In other words (Panofsky uses some Latin terms analogous to the lectio and quaestio and disputatio explained in the previous post), de Honnecourt and Corbie, who are not scholastics, are reaching an ideal design/conclusion using the methods standardized by scholastics. The Latin terms in his last sentence allude to the scholastic Peter Abelard's "Sic et Non" ("Yes or No") in which he discusses 158 contradictory points among church father writings.

You can download a digital copy of Panofsky's work with illustrations here.

But what's this "Album" of Villard de Honnecourt's that he mentions? That's an excellent question. Stay tuned.

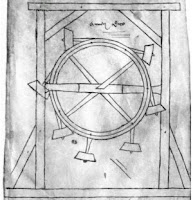

*A chevet is an apse with an ambulatory giving access behind the high altar to a series of chapels set in bays. See the second illustration.