Three men who were considered the founders of Scholasticism (and links to where they've been mentioned here over the years) were Peter Abelard, Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury, and Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury. Many of the Scholastics, or Schoolmen, have been mentioned throughout this blog, some of them quite recently: Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, Albertus Magnus, William of Ockham, Bonaventure, Peter Lombard.

One of its goals was to reconcile the wisdom of classical thinkers with Christian theology. The Toledo School of Translators started making the works of Greek, Judaic, and Arabic scholars available. Interest in the Iberian source of documents inspired some like Adelard of Bath to spend years traveling to where he could find works he could translate, such as Spain and Sicily. Among others, Adelard translated Euclid's Elements of Geometry from Arabic. Adelard also wrote original works; you can get a taste of one here.

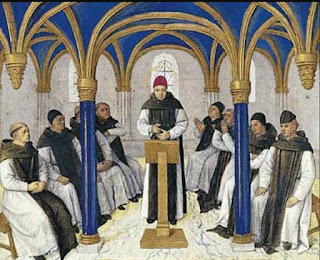

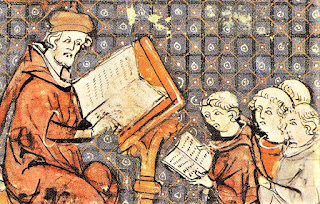

Proper scholastic instruction had three phases: lectio, meditatio, quaestio. Lectio consisted of the master reading an authoritative text, plus any commentary; students listened in silence. This was followed by meditatio when students reflected on what they had heard. Only then would the students be allowed to ask questions. During the quaestio might be raised opposing viewpoints from other authors. This could lead to disputatio, a disputation where two opposing viewpoints debated a topic. (You'll remember a famous Disputation mentioned two months ago.)

A well-known 20th century art historian theorized that scholasticism actually influenced gothic architecture. I look forward to sharing it next.