The formation of a rainbow is a complex matter, inspiring both wonder and curiosity. How they come about took a great deal of time, speculation, and ultimately experimentation.

Aristotle was sure that water droplets were involved, and he knew there was a relationship between rainbow, sun and observer. In his model, however, each water droplet in the air is a tiny mirror that reflects toward the observer a piece of color.

Since each of the mirrors is

so small as to be invisible and what we see is the continuous magnitude

made up of them all, the reflection necessarily gives us a continuous magnitude

made up of one color; each of the mirrors contributing the same color

to the whole. We may deduce that since these conditions are realizable

there will be an appearance due to reflection whenever the sun and the

cloud are related in the way described and we are between them. ... So it is clear

that the rainbow is a reflection of sight to the sun.

[Meteorologica, Book III, Part 4]

Among his other theories,

Robert Grosseteste (c.1175-1235) rejected Aristotle's view that the rainbow was created by reflection; instead, he believed that light passing

through clouds, rather than bouncing

off them, produced the spectrum. Since every schoolchild knows that refraction breaks white light up into the spectrum, this seems to us like Grosseteste knew what he was talking about.

Then came

Roger Bacon a generation later. Some believe he studied under Grosseteste. What is certain is that Bacon knew of Grosseteste's works, because he sometimes quotes them verbatim in his own writing. When it comes to the rainbow, however, Bacon does something that seems baffling on the surface. He rejects the refraction theory and returns to Aristotle's reflection theory. Modern historians shake their heads over this apparent retrograde thinking.

|

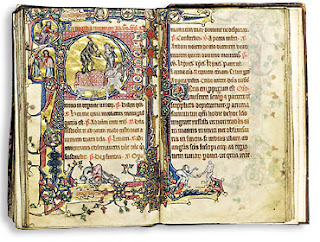

| Christ on a rainbow, the Macclesfield Psalter |

Bacon had his reasons, however, which make more sense once you know the details of Grossesteste's theory. Grosseteste required three separate refractions to take place, using the borders of the clouds in a complicated lensing effect. Bacon pointed out that a rainbow could appear in a simple spray of water, as in a fountain, and the clouds and interfaces needed for the complex refractions described by Grosseteste were clearly not involved. Bacon also pointed out that the view of the rainbow changed as the observer moved, which meant the rainbow was being

reflected toward the observer while keeping its proportions and color. It did not stay "painted on the clouds" as if it were just projected there by light refracted through a cloud lens. (At this point, it is obvious that they did not yet understand "seeing" as light reflecting off objects and into the eye.)

Bacon didn't have all the answers, of course. He struggled to explain the curve in the rainbow, and the fact that it was not a solid half-sphere: why wasn't there color in the center? And he ignored refraction completely when discussing the rainbow, even though he used refraction to explain the occasional halo around the moon.

Did Bacon hold back scientific progress? Hard to say. Grosseteste's theory was valuable in that refraction is crucial in the formation of a rainbow, but he made several assumptions that could not be supported. He ignored the part played in the process by water droplets, even though Aristotle and—more recent to Grosseteste, Albertus Magnus (c.1200-1280)—had insisted on the part they played. Grosseteste thought the

entire cloud was the refracting lens. Rainbows were still not properly understood, but the efforts made to comprehend something that could not be touched and experimented on were impressive.*

...and what of the accurate explanation of the rainbow? A few years after Bacon's death, a disciple of Albertus Magnus would work it out. But that's for another day.

*

More on Grosseteste, Bacon and their theories can be found in an article by David C. Lindberg in Isis, Vol.57, #2 (1966).

The illuminations of the Gorleston Psalter are usually represented by a fox carrying a goose in its mouth (the duck is actually saying "queck"); this may be because it is the only straightforward image that doesn't take a left turn into the fantastical. Above (from the article) is a bishop bowing his head before the executioner's axe; the executioner is a rabbit.

The illuminations of the Gorleston Psalter are usually represented by a fox carrying a goose in its mouth (the duck is actually saying "queck"); this may be because it is the only straightforward image that doesn't take a left turn into the fantastical. Above (from the article) is a bishop bowing his head before the executioner's axe; the executioner is a rabbit. Interest in the Gorleston Psalter was revived about a decade ago when the Macclesfield Psalter unexpectedly surfaced. The artwork in the Macclesfield was so similar to the Gorleston that it is accepted that the artist and copyist was the same for both. Internal cues link both to the church of St. Andrew's in Gorleston. The owner put the Macclesfield Psalter up for auction at Sotheby's. It was about to go to California until a coalition of several British celebrities began a funding campaign that matched the winning bid of £1.7 million and kept the Psalter in England.

Interest in the Gorleston Psalter was revived about a decade ago when the Macclesfield Psalter unexpectedly surfaced. The artwork in the Macclesfield was so similar to the Gorleston that it is accepted that the artist and copyist was the same for both. Internal cues link both to the church of St. Andrew's in Gorleston. The owner put the Macclesfield Psalter up for auction at Sotheby's. It was about to go to California until a coalition of several British celebrities began a funding campaign that matched the winning bid of £1.7 million and kept the Psalter in England.