For a time, in his youth, he was at Queens College in Oxford. There are no records saying he was enrolled (he would have been very young at the time, considering that he was away from Oxford by the time he was sixteen, fighting the Battle of Shrewsbury), but there is other evidence to examine.

For one, his uncle Henry Beaufort was chancellor there from 1397-99. A resident of Oxford named John Rouse affirms in a history that Henry studied there "under the guardianship of his uncle Henry Beaufort, then Chancellor of Oxford."

As king, Henry supported Queens College's rights in a dispute with Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Arundel. After this, Henry made sure that Queens would not be bothered by Canterbury, and instead put it under the protection of the Archbishop of York.

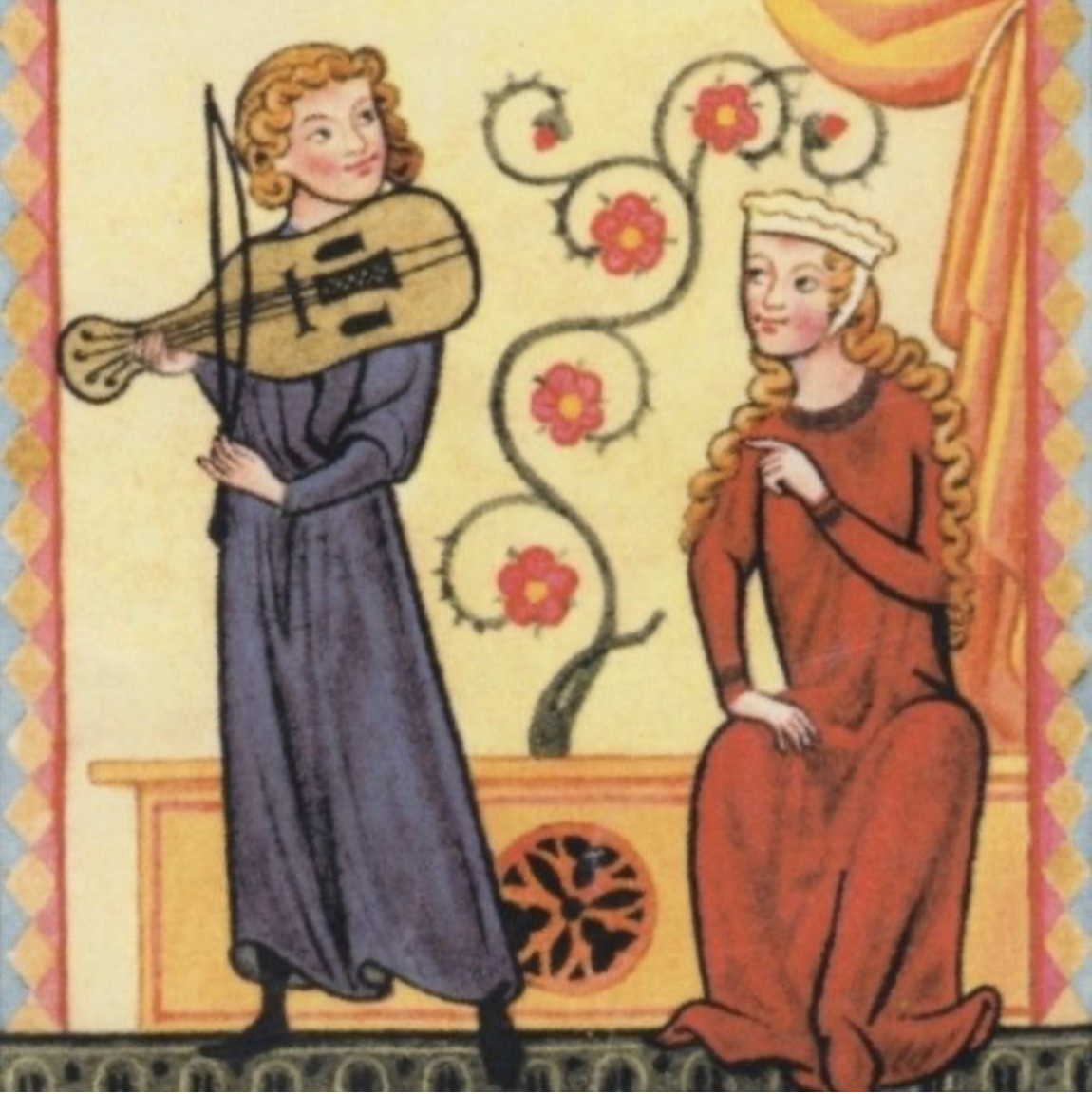

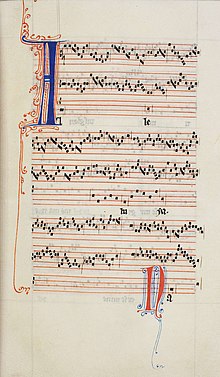

It is also recorded that he learned to appreciate literature and music while at Queens. Prior to Queens he had learned the harp, the recorder, and the flute. While campaigning in 1421 in France he even had a harp delivered to him. As king he granted pensions to musical composers. He is even known to have set to music two parts of the Mass, the Gloria and the Sanctus. Note the illustration and the words in red in the upper-left corner: "Roy Henry." The music is "highly skillful" and was possibly done with help from a professional composer. You can hear the selections at this link.

In a first for an English king, he learned to write in the Middle English vernacular.

Most people's knowledge of Henry is based on Shakespeare's plays. If they remember anything about the plays, it is probably the larger-than-life character of Falstaff. Falstaff was based on a real friend of Henry, Sir John Oldcastle. And yes, Henry had to change his attitude toward Oldcastle radically from when he was a prince. The colorful Sir John Oldcastle and his fate is a good tale for next time.