16 March 2025

William of Tyre

27 October 2024

The Siege of Paris

On the way to Paris, many towns easily switched their allegiance to the new king. On 15 August, however, the Armagnacs came up against English forces in a fortified position led by the Duke of Bedford. Joan rode alone against the English, hoping they could be goaded to leave their fortifications and attack, but they stayed put. For whatever reason, however, the English retreated the next day, and the Armagnacs were able to continue their march to Paris, which they reached on 8 September.

The Siege of Paris turned out to be a turning point for Jeanne. She was wounded in the leg by a crossbow bolt and hid in a trench until nightfall, when she could be rescued. Fifteen hundred Armagnac casualties led Charles to call off the assault. Jeanne argued against this course of action, but the Armagnacs retreated.

Jeanne insisted on fighting, but the court wanted a diplomatic solution. The failure of the Siege of Paris reduced the army's faith in her. Scholars at the University of Paris concluded that her involvement in the army was not, in fact, divine as they had thought.

She was allowed, in October, to be part of a force sent to deal with a mercenary. A siege and attack urged by Jeanne succeeded, but attempts to retake another town failed, further diminishing faith in Jeanne.

Nevertheless, in December, upon her return to court, she found that Charles had ennobled her family as a reward for services. She also discovered that a truce had been made with the Burgundians which would last until Easter 1430, so her services as a soldier were not needed.

She took matters into her own hands, however, and still had influence over many who believed in her mission. Her independent attempts to drive out the Burgundians and English led to her downfall, however, which I will go into tomorrow.

08 December 2023

Gerald of Wales

He was of both Norman and Welsh descent, a child of the conquerors and the conquered. Educated at the Benedictine house at Gloucester, he was employed by Becket's successor, Richard of Dover, and trusted to manage affairs in Wales such as abuses of consanguinity laws and Welsh church finances. After revealing the existence of a mistress of the archdeacon of Brecon, Gerald was appointed to replace him. The position had a small estate at Llanddew, allowing Gerald to collect tithes of wool and cheese.

His lifelong goal was to become Bishop of St. Davids in Pembrokeshire, Wales. When his uncle (then Bishop of St. David's) died in 1176, the chapter nominated Gerald. King Henry II rejected Gerald's appointment; he may have thought Gerald would be too independent—Wales was hoping to split from the authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury—and Henry had just got over the troubles he had as a result of Becket's martyrdom. Henry appointed a loyal Norman retainer, Peter de Leia. Gerald was also cousin to Rhys ap Gruffydd, a Welsh lord who was understandably hostile to Norman rule. Peter de Leia's relationship with Gruffydd was less than amiable, and Henry liked it that way.

Gerald's historical account includes this (possible) statement from Henry:

It is neither necessary nor expedient for king or archbishop that a man of great honesty or vigor should become Bishop of St. Davids, for fear that the Crown and Canterbury should suffer thereby. Such an appointment would only give strength to the Welsh and increase their pride.

Gerald consoled himself by leaving the country. He spent a year at the University of Paris, studying and teaching canon law and philosophy. In 1180, back in England and continuing to study theology, Bishop Peter de Leia offered him a minor position in the Bishop's household, which he at first accepted but shortly gave up.

Where he becomes of greater interest to modern scholars is in 1184 when he was asked by King Henry to mediate between the Crown and Rhys ap Gruffydd. After, he was sent with Prince John to Ireland, which led to his first important writing: Topographia Hibernica ("Topography of Ireland," although it was mostly history). Not long after he wrote Expugnatio Hibernica ("Conquest of Ireland"), the story of Henry's military campaign there. Both works were revised several times during Gerald's lifetime.

This was the start of both his writing career and his work with several kings. We'll pick up with his map of Ireland—and how his writings were influential right into Tudor times—tomorrow.

27 October 2023

Causes of the Bubonic Plague

King Philip VI of France asked the University of Paris to determine the cause. Forty-nine members of the medical staff studied the matter and wrote the Paris Concilium.

They produced more than one theory of why humans were suffering from it, while maintaining that the plague was too mysterious for human beings to ever truly understand the origin. They drew from the available authorities: Avicenna's work on pestilential fever, Aristotle's Meteorology on weather phenomena and putrefaction, Hippocrates' Epidemics on astrology in medicine.

Their theories:

—The Concilium followed Aristotle's idea that a conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn was disastrous. Albertus Magnus believed a conjunction of Jupiter and Mars would bring plague. A conjunction of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars took place in 1345 right after solar and lunar eclipses, under the sign of Aquarius, compounding the disastrous effects of the planets. Jupiter was sanguine, hot and wet—the worst combination that would lead to putrefaction.

—Another possible cause was poisonous gases released during earthquakes. Disadvantageous conjunctions of constellations produced winds that distributed gases rising from rotting carcasses in swamps. The poisonous vapors would be inhaled and go straight to the heart (they thought the heart was the organ of respiration), and then cause the body's vital organs to rot from the inside.

—There was also the possibility of God's punishment for man's wickedness.

Of course, there was no reason to believe that these causes were mutually exclusive.

The plague was devastating, and also didn't end in 1351. It remained endemic to Europe, as I'll discuss next time.

25 June 2023

Female Physicians

Consider that, technically, anyone could practice medicine. No one would object to a mother caring for a family member, or a nun feeding a leper (as in the illustration). More formal, professional medical practice in France, however, required a degree from the University of Paris. This prevented many, women especially, from helping their fellow human beings. There were consequences for treating the sick if you were not "official."

Consider the case of Jacqueline Felice de Almania, a woman from Florence who was living in Paris. Her reputation was excellent: she was known for finding cures for patients who had been treated elsewhere without relief. She did not charge fees unless the patient was cured.

In 1322, she was brought to trial by the University of Paris. The accusation was treating patients without any "real" knowledge of medicine; that is, she did not have a degree. Seven former patients were brought as witnesses; all testified that she had helped them where male doctors had failed. Her actions involved analyzing urine by sight, taking the pulse of patients, examining their limbs, etc. She was found guilty of practicing without a license, fined 60 pounds, and threatened with excommunication if she ever treated patients again.

The year 1322 was popular for cracking down on unlicensed medical practitioners. In that same year, records show women named Clarice of Rouen (banned for treating men), Jeanne the Convert (likely originally a Jew) of Saint-Médicis, Marguerite of Ypres, and "Jewess Belota" all were banned from practicing medicine.

The University of Paris in 1325 appealed to Pope John XXII to speak out strongly on this issue. He wrote to Bishop Stephen of Paris to forbid women practicing without medical knowledge or acting as midwives, because what they were doing was akin to witchcraft. A bit of a stretch to go from medicine to witchcraft just because the person was female, but then, John was determined to stamp out witchcraft...and a lot of other things, which I'll talk more about tomorrow.

(By the way, women earning medical degrees at the University of Paris was suppressed until the 19th century!)

06 April 2023

John of Garland

He left Toulouse around 1232 when the Cathars re-asserted themselves and university professors stopped being paid. He fled to the University of Paris, where Roger Bacon heard him lecture. It was this time in Paris that gave him his surname: he explains it is from the Rue Garlande in the neighborhood of the University.

There are over two dozen of his writings known (there are a few titles we know of, but have no extant copies). One was his Dictionarius (shown here), which was not a dictionary as we know it, but a textbook that attempted to teach Latin to French students at the University of Paris. Some credit Garland for the origin of the modern word "dictionary."

Besides works of instruction, he wrote poetry such as the Epithalamium beatae Mariae Virginis (“Bridal Song of the Blessed Virgin Mary”) and his account of the crusade against the Cathars, De triumphis ecclesiae (“On the Triumphs of the Church”). His hostility toward heresy was extended to Jews. To quote an author who wrote about this topic:

Although he never denied the possibility that conversion to Christianity could redeem the Jews, he thought it unlikely they would come over to the Catholic faith or remain steadfast in the religion. His invective was extreme by the standards of the time but was influential in that it appeared in many of his pedagogical works for adolescents and young men at the universities. [Journal of Medieval History, Vol.48, Issue 4]

Despite his time in France, his numerous writings were very popular in England, and were printed and re-printed in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Curiously, there was a second John of Garland who lived and wrote about the same time; this one was a music theorist, and will be our next topic.

24 October 2022

Simon Sudbury

13 July 2022

Jacques de Vitry

Born at Vitry-sur-Seine (hence the surname) near Paris about 1160, he studied at the recently founded University of Paris. After an encounter with Marie d'Oignies, a female mystic, he was convinced to become a canon regular (a priest in the church, as opposed to a monk), so he went to Paris to be ordained and then served at the Priory of Saint-Nicolas d'Oignies. He strongly preached for the Albigensian Crusade.

On the other hand, he was fascinated by the Beguines, a lay Christian group that operated outside the structure of the Church, and asked Honorius to recognize them as a legitimate group.

His reputation was such that in 1214 he was chosen bishop of St. John of Acre, in the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem. From that experience he wrote the Historia Orientalis, in which he recorded the progress of the Fifth Crusade, as well as a history of the Crusades, for Pope Honorius III. He never finished the work. Besides leaving many sermons, he also wrote about the immoral life of the students at the University of Paris.

In 1229, Pope Gregory IX made de Vitry a cardinal. A little later he died (1 May 1240) while still in Jerusalem. His body was returned to Oignies. His remains were held in a reliquary. In 2015, a research project determined that the remains in the reliquary likely were, in fact, de Vitry's. Forensic work on the skull and DNA evidence contributed to a digital reconstruction of his head and face.

The Beguines were only mentioned here briefly, and deserve more attention. They will come next.

18 March 2022

Thomas Aquinas

He was born in 1225 in the town of Aquino. His father was Count Landulph of Aquino, his mother Countess Theodora of Teano; he was related to the kings of Aragon, Castile, and France, as well as to Emperors Henry VI and Frederick II. A biography written a generation after he died claims that a holy hermit predicted to a pregnant Theodora that her child would become unequalled in learning and sanctity.

His education began at the typical age of five, with the Benedictines of Monte Cassino (his father's brother Sinibald was the abbot there from 1227-1236). Some time between 1236 and 1239 he was sent to a university at Naples where he would have first learned about Aristotle, Averroes, and Maimonides. Here he also came into contact with a Dominican preacher. The Dominicans had been founded 30 years earlier and were actively recruiting.

When he was 19 years old, Thomas announced that he wished to join the Dominicans, which displeased his "Benedictine-oriented" family. It displeased them so much that, while Thomas was traveling to Rome on his way to Paris to get away from the family's influence, his brothers (at his mother's request) kidnapped him. He was forced to stay in his parents' castle for almost a year, spending the time tutoring his sisters.

Attempts to dissuade him from the Dominicans became more desperate. His brothers sent a prostitute to seduce him. He fought her off with a burning log, then fell into a mystical trance and had a vision of two angels granting him perfect chastity. (They also gave him a "girdle of chastity" that now resides in Turin.) His mother, seeing that he would not change his mind, and not wanting to endure the embarrassment of allowing her son to join the Dominicans, she arranged for him to escape his home in 1244. He went to the University of Paris where he probably studied under Albertus Magnus. Because Thomas was quiet, his fellow students ridiculed him, but Albertus is supposed to have told them "You call him the dumb ox, but in his teaching he will one day produce such a bellowing that it will be heard throughout the world."

In 1256 he was appointed regent master in theology at Paris and began writing the first of his many theological works, Contra impugnantes Dei cultum et religionem ("Against Those Who Assail the Worship of God and Religion"), defending the mendicant orders.

His reputation as a theologian and teacher/preacher grew so much that he was granted the Archbishopric of Naples in 1265 by Pope Clement IV, but he turned it down. In the yard that followed he would have the time to write one of his greatest works, the Summa Theologica.

And this is where we come back to the comparison with Maimonides: despite the groundbreaking nature of his writing, which became foundational for much of what followed, he was not without his detractors. Some of his conclusions clashed with accepted thought from previous religious writers. To be able to discuss that, we should look at two other philosophers: Aristotle and Averroes. Stay tuned.

12 February 2022

University of Paris - The Strike

In March 1229, University of Paris students—normally boisterous and given to drinking heavily—were enjoying the pre-Lenten Mardi Gras-like atmosphere (it was Shrove Tuesday and the beginning of Lent). An argument broke out between a band of students and a tavern proprietor over the bill; a fight ensued, resulting in the students being beaten by the townspeople and tossed out.

The students returned the next day, Ash Wednesday, with friends and clubs. They trashed the tavern and beat the taverner. A riot started that damaged nearby shops. The students thought themselves free from punishment, because university students had benefit of clergy. The King's courts couldn't touch them, and the ecclesiastical courts tended to be protective of university students, who were all potential clergy.

The King of France at the time, Louis IX, was only 15 years old. The regent in charge of royal affairs decided the students' crime could not be allowed to go unpunished. The Paris city guard, not known to be gentle toward university students anyway, were given permission to mete out punishment. They found a group of students and killed several. There is no proof that the guardsmen had attacked the actual instigators of the original trouble.

The university went on strike. Teaching ceased. Students left, taking their spending money with them. The economy of Paris suffered. Students and teachers wound up in Reims, Oxford, Toulouse, and some went to Orleans and started teaching there.

In 1231, Pope Gregory IX (an alumnus!) issued a decree that the University of Paris was under papal patronage, making it independent of any local authority. Masters were allowed to cancel classes for almost any provocation; the threat of economic losses kept the city in line.

If the regent had not stepped in, who knows what would have happened? More rioting? Or just moving beyond the incident. No dispersal of university staff and students might have meant no university at Orleans or elsewhere? We will never know. But we do know who the regent was who caused that turning point: Blanche of Castile. I'll tell you about her tomorrow.

11 February 2022

Orleans University

The University of Orleans started in 1230, when several; teachers and students fled the turmoil taking place at the University of Paris. Pope Clement V (1264-1314) studied there, and as pope published a papal bull in 1306, endowing the scholarly pursuits there with the status of university. In all, twelve popes granted it privileges.

In the 1300s it had as many as 5000 students from France, Germany, and even Scotland. Eustache Deschamps was one. St. Ivo of Kemartin, the patron saint of lawyers, was another. Later notables were John Calvin, Pierre de Fermat (of Fermat's Last Theorem fame), and Molière.

The current University of Orleans was founded in 1960. The original had been merged with the University of Paris in 1808.

Speaking of the University of Paris, what was the turmoil that caused teachers and students to flee to Orleans and start teaching there? We'll get into that next time.

09 December 2015

The Talmud Compromise

A converted Jew had presented to Gregory 35 places in the Talmud that he considered blasphemous to Christianity. This led to the Disputation of Paris (about which I really should write a post soon). After the Disputation, a tribunal was assembled to decide whether the Talmud was dangerous to Christianity. One of the men involved, Odo of Châteauroux (c.1190 - 25 January 1273), was chancellor of the University of Paris. The decision of Odo and the tribunal was that the Talmud was heretical and should be burned.

|

| Burning the Talmud |

In 1247, the pope listened to complaints brought to him by some Jews, and he asked Odo to take a second look, but this time to try to see it through the eyes of the Jewish rabbis. Was the Talmud truly heretical and a danger to Christianity, or merely misguided and could be treated simply as an error-prone text and studied as such, the way philosophy would be treated. He thought that the Talmud might prove harmless, and that the confiscated copies might be returned.

Odo was having none of it, and he condemned the Talmud again, in May 1248. Innocent listened carefully, and also listened to the rabbis who claimed that they could not understand the Bible if they did not have their Talmud, which was so intertwined with the Old Testament. Against the objections of Odo and others, Pope Innocent decreed that the Talmud should not be burned, merely censured as erroneous insofar as Christianity is concerned. He decreed that the Talmuds in possession should be returned to their owners.

The popes after Innocent continued this policy.

21 August 2014

Geert Groote

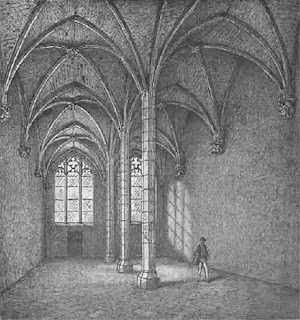

|

| A 19th century depiction of Geert Groote's Brethren of the Common Life |

In 1362 he became a teacher in Deventer, where his success and reputation encouraged him to adopt a lavish lifestyle, until a fellow student, Henry de Calcar, made him see the inappropriateness of this. Groote started to change in the early 1370s, inclining toward mysticism and a more humble life. In fact, he gave his worldly goods to the monastic Carthusians and started preaching a life of repentance.

He gathered a small band of followers who called themselves Broeders des gemeenen levens [Dutch: "Brethren of the Common Life"]. The Brethren did not take vows, but merely gave up their possessions to live in a community where they devoted their waking hours to mass, religious reading and preaching, and manual labor. Meals were eaten as a group, with Scripture read aloud. It had all the hallmarks of a monastic life without the need to be clergy. They founded schools; Nicholas of Cusa attended one.

Before he died (20 August 1384), he organized some of the Brethren who wanted a more "regular" life into Augustinians; he died before this plan was complete, but his disciple Florens Radewyns established a monastery at Windesheim that became the center of up to 100 monastic houses called the Windesheim Congregation.

Groote promoted a style of piety now referred to as Devotio Moderna ["Modern Devotion"]. It was a search for inner peace based on self-deprivation and silent meditation on Christ's Passion. One of the students in his school, Thomas à Kempis, was inspired to write The Imitation of Christ, a work that (I believe) has never been out of circulation since the 15th century.

12 June 2014

Ars Nova: Jean de Muris

|

| Treatise on Musical Intervals, by Jean de Muris |

Born near Lisieux about 1300 (he died c. 1351), he studied at the University of Paris and spent a lot of his time there as well as at Evreux, Fontevrault and Mezières-en-Brenne. He wrote a few books—perhaps as many as five (we are not sure whether some were written by him, but similar style is a reason for ascribing some works to him).

There are over 150 manuscripts of copies of works attributed to Muris. At one point, a work that criticized the Ars Nova was considered to have been written by him, but later it was determined that someone else wrote it. Muris certainly approved of the new style in his works. One of these, the Quæstiones super partes musicæ ["Questions on the parts of music"], can be read (in Latin) here.

Here's a section in English:

What is music? Music is the mistress art of the arts, containing in herself the beginnings of all methods [...], confirmed in the nature of all things, remarkably internalized proportionally, delightful to the intellect, loved by the ear. Music gladdens the downcast, rewards the eager, thwarts the envious, comforts the weak, keeps awake the vigilant, awakens the sleepers, nourishes love, honors its possessor, if music, which was established at last for the praise of God, has pursued its just goal. [link, p.239]This embodies the Ars nova, which brought formal music out of the Church and made it complex, expressive, and secular.

20 May 2014

A King, a Cardinal, and a College

|

| Sancho in a contemporary manuscript |

Unfortunately, he could even be harsh to his own supporters. One of his most loyal supporters was Lope Díaz III de Haro—who was, among other things, Sancho's brother-in-law—but Sancho killed him in 1288 during an argument in which Lope threatened Sancho.

On 20 May 1293, King Sancho IV of Castile granted a royal charter to the Archbishop of Toledo to create a university in the city of Alcalá de Henares. It was called the Studium Generale ["School of General Studies"]. The archbishop, Gonzalo Garciá Gudiel, had been born in Toledo but studied at the University of Paris and become rector at the University of Padua. Wishing to create a university in the place of his birth, he convinced Sancho to give him some land and the charter. Sancho called him chanceller mayor en todos nuestros regnos ["great chancellor in all our realms"].

In 1499, an alumnus of the Complutense University (Complutum was the Latin name for Alcalá), Cardinal Cisneros, received a papal bull from Pope Alexander IV (seen here endorsing the Sorbonne) that allowed him to purchase more land for the expansion of the university. In the 16th and 17th centuries, students from all over Europe flocked to study there, in philosophy, canon law, medicine, philology, or theology. Famous alumni included Ignatius Loyola, founder of the Jesuits.

Complutense granted a doctorate to a female student in 1785, 135 years before Oxford even accepted female students! The university grew so large that, in the 20th century, it was moved to Madrid and given more buildings to accommodate its needs.

22 October 2013

Duns Scotus

His contemporaries refer to him as Johannes Duns, and since there was a practice of using the Christian name plus place of origin, it is assumed that he came from Duns in Scotland (although a very late notation on a copy of his "final exam" on the Sentences of Peter Lombard claims he was from Ireland). We know that he was accepted into the Franciscans on 17 March 1291. Since the earliest age at which he could be accepted into the Order was 25, and since we assume he was accepted as soon as his age allowed, we surmise that his year of birth was 1265 or 1266. That encompasses most of what we "know" of the personal life of the figure who was called Doctor subtilis [Latin: Subtle doctor] due to his penetrating philosophical and theological insights.

He got into some trouble in June 1303 while lecturing at the University of Paris. King Philip IV "the Fair" of France (previously mentioned here) was taxing church property. Understandably, he was being opposed by Pope Boniface VIII. Scotus sided with the pope and was expelled from France with about 80 other friars. They were back about a year later.

Although he never wrote a giant compendium of all his thought the way others like Thomas Aquinas did, he is known for numerous commentaries in which he untangled many of the theological controversies of the day. Hence the title "Subtle doctor." His argument for the existence of God "is rightly regarded as one of the most outstanding contributions ever made to natural theology." [source] It has numerous details, but boils down to:

(1) No effect can produce itself.

(2) No effect can be produced by just nothing at all.

(3) A circle of causes is impossible.

(4) Therefore, an effect must be produced by something else. (from 1, 2, and 3)

(5) There is no infinite regress in an essentially ordered series of causes.

(6) It is not possible for there to be an accidentally ordered series of causes unless there is an essentially ordered series.

(7) Therefore, there is a first agent. (from 4, 5, and 6)

Both (5) and (6) have several sub-arguments, and after (7) he moves on to further details. His underlying assumption that makes much of his thought work is that God is infinite.

He also championed the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, quoted in 1854 by Pope Pius IX in his declaration of that dogma.

Pope John XXIII (1881-1963) recommended Scotus' writings to theology students. In 1993, Pope John Paul II (1920-2005) beatified him.

There was a movie made about him in Italy in 2011, available on Amazon.