It was called Brehon Law because it was administered by Brehons (from Old Irish breithem ("judge"), successors to Celtic Druids who acted as arbitrators in disputes, and questions of compensation and conduct.

Brehon Law recognized equality between sexes and concern for the environment. It was progressive in that it promoted restitution rather than punishment after wrongdoing. Even homicide and bodily harm were recompensed according to an established scale of value, similar to the Anglo-Saxon wergild. Payments were made to the family, not to a civil court. Capital punishment was not part of Brehon Law, unlike many other legal systems before and since, and revenge and retaliation were strongly discouraged.

The clan was the most important social unit, and the property inhabited by that clan was treated as communal when it came to resources such as bee hives, fruit trees, and water mills. The seventh-century Coibnes wisci thairidne ("The Kinship of Conducted Water") discusses the importance of water and why it belongs to all.* Land itself was rarely sold; the highest-ranking lord "rented out" not the land but the right to graze cattle on it.

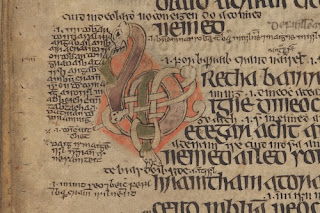

The manuscripts in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin (sample shown above) offer an extensive look at this early legal system. This particular illustration is part of a discussion of Bechbretha ("bee judgments"). Honeybees were an important part of the economy: people needed honey, and monasteries needed large amounts of beeswax. Bees were protected; bee possession was sacrosanct; but if you came across a swarm of bees (a mass clinging together on a branch, waiting for the secret apian signal to fly and find a new home), you could claim it for your own and remove it for your use.

Women in marriage had more agency than in Roman Catholic countries at the time, and I'll go into marriage and divorce tomorrow.

*Even in the 20th century, James Joyce has Leopold Bloom ask "How can you own water really?" in Ulysses.