When Richard first succeeded his father, it was Walter as Archbishop of Rouen (a position he had thanks to Richard's father) who absolved him of his youthful rebellion against Henry. Walter went with Richard on the Third Crusade. He got as far as Sicily before Richard got word that there were problems between Prince John, Richard's younger brother, and William Longchamp, the justiciar who had been left in charge of England. Richard trusted Walter to mediate between the two. Longchamp created further problems, however, that caused Walter to take over his duties, if not formally the title, until 1193.

When Richard was being held captive by Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, the ransom price was 100,000 pounds of silver. It was not paid all at once, however, and Henry did the honorable thing by allowing Richard to depart captivity once the first payments had arrived and the rest was pledged. In cases such as this, however, guaranteeing that the rest of the payments would arrive was often done by substituting a valuable person as hostage in place of the primary.

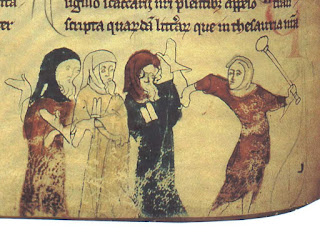

Richard called Walter to Germany to take his place. Walter remained there from 1193 to 1194 when the final payments were made. Afterward, Walter chose to remain in Normandy and not return to England. When Richard wanted the site of Andeli, which was in Walter's hands, Walter refused. The revenues from owning that property were valuable to the archbishop. Richard seized the spot anyway, which seemed discourteous to the man who had been a valuable member of the court and sat in prison on Richard's behalf. Richard needed the site for his war against Philip of France, however. Walter placed Normandy under Interdict, meaning no church services could be performed. This included funeral rites: Roger of Hoveden (who also went on the Third Crusade) commented on "the unburied bodies of the dead lying in the streets and square of the cities of Normandy."

Walter went to Rome to get Pope Celestine III to intercede on his behalf. Richard also sent an embassy. Richard made gifts of other lands to Walter and to the diocese of Rouen, including the port city of Dieppe, sufficient to prompt Celestine himself to remove the Interdict. Walter had little to no contact with Richard after this incident. After Richard's death, he had to deal with King John, and I'll talk about that time period next time.