One of its condemnations was of the Beguines and Beghards. These were groups of (respectively) laywomen and laymen who created communities of folk who wanted to live simple lives devoted to prayer and good works. Their lifestyle mirrored that of monks, but they took no formal vows. The difficulty for the Council was that these groups were accused of believing that they could achieve their own salvation independent of the guidance of religion (or the authority of the Church) by living their lives simply. Pope Clement V produced an encyclical from the Council condemning the groups as heretical. In some areas, Beguines and Beghards were actually burned.

Another conflict between formal and informal spirituality was sparked by Ubertino de Casale (a significant figure in the book and movie The Name of the Rose). He complained that a stricter adherence to the Rule of St. Francis was necessary, especially regarding the vow of poverty. Those following this stricter rule were called Spirituals, and they were opposed by the leaders of the Franciscans, who were straying away from the vow of strict poverty. The outcome of the Council was a bull from Clement left decisions of behavior up to the individual abbots.

The Council embedded in canon law that priests must not marry, and laid out punishments for adultery, concubinage, fornication, incest, and rape.

A crusade was discussed, because the King of Aragon wanted to attack the Muslim city of Granada. Philip IV of France on 3 April 1312 (the Council ended the following May) vowed to go on Crusade within the next six years, but Clement said he had to start within the next year and Philip must lead it. A tithe was begun to raise funds for the Crusade, but Phillip died in November 1314.

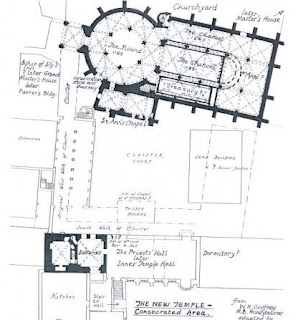

One of the biggest decisions to come out of the Council was regarding the Knights Templar. When Clement called the Council by a bull in August 1308, saying the Templars would have to answer for their actions in a new ecumenical council in 1310 (it was obviously delayed). This bull created papal commissions to investigate the Templars and take depositions that would be brought to the pope.

The fate of the Templars has been discussed many time in this blog, but Ubertino de Casale has not, so tomorrow we'll look at his life and impact on the Franciscans.