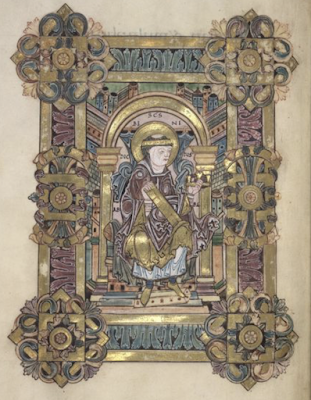

The Olivetans, or the Order of Our Lady of Mount Olivet, was "started" in 1313 by Bernardo Tolomei (10 May 1272 – 20 August 1348; see illustration), a Tuscan who was educated by his Dominican uncle and determined to enter the religious life. Originally named Giovanni, after becoming a professor of law at the University of Siena and spending time as a soldier/knight under Rudolph I of Germany, he changed his name to Bernardo (after the Cistercian Bernard of Clairvaux) and started living as a hermit with two friends on property owned by his family.

Somewhere around late 1318 or early 1319, Bernardo had a vision of a ladder with monks dressed in white ascending with the aid of angels to where Jesus and Mary waited for them. He decided to formally found his Order in 1319, using the Rule of St. Benedict, with particular devotion to the Virgin Mary. Pope Clement VI recognized the Order in 1344. A generous merchant constructed a monastery for them at Siena, and several more sprang up in the following years.

Unfortunately for Bernardo, he did not live to see the Order thrive for very long after its recognition by Clement. When the Bubonic Plague came to the shores of Italy, Bernardo and several monks left the relative solitude and safety of their monastery to Siena, where the people were suffering greatly. The monks tended the sick, and Bernardo himself along with 82 fellow monks contracted the disease and died.

The order survived, however. In 1408, Pope Gregory XII gave them an unused monastery of St. Justina of Padua. Even now they still have 20 houses, although the total number of monks, nuns, and priests in the Order are fewer than 500.

The Benedictine Congregation has 19 different groups, 14 of which were founded after 1500. Some, however, are much older than the Olivetans, and I'd like to share some of their stories starting tomorrow.