Kublai chose the 17-year-old Kököchin, of the Chinese Yuan dynasty. Her escort to the Ilkhanate included three of Kublai's envoys and a young Venetian named Marco Polo. Marco, along with his uncles, had been "guests" of Kublai for many years. Kublai did not want to lose the company of his foreign guests, but his envoys insisted. In the words of Marco Polo from his account:

The overland road from Peking to Tabriz was not only of portentous length for such a tender charge, but was imperiled by war, so the envoys desired to return by sea. Tartars in general were strangers to all navigation; and the envoys, much taken with the Venetians, and eager to profit by their experience, especially as Marco had just then returned from his Indian mission, begged the Khan as a favour to send the three Firinghis* in their company. He consented with reluctance, but, having done so, fitted the party out nobly for the voyage, charging the Polos with friendly messages for the potentates of Europe, including the King of England.

There were problems on the voyage

involving long detentions on the coast of Sumatra, and in the South of India, ...; and two years or upwards passed before they arrived at their destination in Persia. The three hardy Venetians survived all perils, and so did the lady, who had come to look on them with filial regard; but two of the three envoys, and a vast proportion of the suite, had perished by the way.

Not only had some of the escorts died along the way, but so had Arghun by the time his anticipated bride had arrived. In fact, he had died before the escorts had even set out, a fact they did not know until they had arrived.

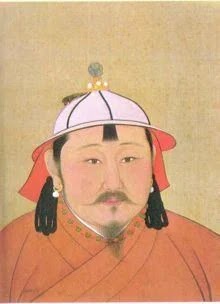

The trip was not wasted, however, because Arghun had a son, Ghazan, who was about the same age as the princess Kököchin. Although not as handsome as his father, he was in many ways an excellent ruler and war-leader. He also had good diplomatic relations with Europeans and the Crusaders. Let's talk more about Ghazan Khan tomorrow.

*Firinghis or farang is Persian and originally intended to refer to Franks, lumping all Western Europeans together.