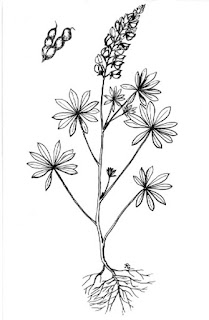

The lupin had a couple strikes against it. Although edible, it had a bitterness due to alkaloids; some varieties with less alkaloid content are called "sweet" lupins. Also, it had a bad reputation for "devouring" all the resources needed by other plants. The name comes from Latin lupinus, "of the wolf," the adjectival form of lupus, "wolf."

Despite this, Romans spread lupin use throughout the empire, soaking it in water before feeding it to humans or livestock. Failing to soak them in water long enough to leach out the alkaloids would lead to poisoning symptoms. (It is possible that our understanding of the name is less about devouring resources and more about what improperly prepared beans did to the consumer. Consider that the same Latin word for wolf also gives us the modern lupus to refer to a wasting disease. I cannot find a corroborating source for this theory, but it makes me wonder.)

On the other hand, the lupin was prescribed in Anglo-Saxon England for "devil-sickness." Lupins are high in manganese, and manganese deficiency is linked with recurring seizures. Is it possible that Northern Europe discovered the lupin as a treatment for epilepsy? This does not appear in any Mediterranean medical sources.

De Crescenzi saw value in the lupin as part of crop rotation:

Better still was the lupine. When raised for seed as one of the crops in a rotation, it was sown in October or November and harvested in June or July. When it was raised for fodder, it was cut somewhat earlier, but in either case it protected the land against winter rains. Several species were native to Italy, but Crescenzi made no distinction as to their use or method of cultivation. Some varieties of beans or vetch were occasionally substituted for lupine in rotations. [from Pietro De Crescenzi: The Founder of Modern Agronomy, Lois Olson, Agricultural History, Vol.18, No.1]

These days, the lupin/e (of which there are hundreds of varieties) is used for high-protein, high-fiber, and low-fat livestock feed, as well as for a nutritious flour substitute; and let's not forget its place in many gardens!

Its application as a treatment for epilepsy is an interesting twist, though, and makes me wonder how else the Middle Ages tried to explain and cure this particular ailment. Let's take a look at that next time.