In 964, therefore, Æthelwold called on military support from King Edgar the Peaceable to expel all those clerics and bring in disciplined monks from Abingdon Abbey to re-establish proper Benedictine Rule. Although other monastic leaders of his time (including his friend Dunstan) allowed a mix of monks and secular clergy, Æthelwold clearly did not trust priests, whom he saw as undisciplined. In his writings he often referred to clergy as "filthy."

Edgar and his queen, Ælfthryth, offered their support, and Æthelwold wanted them to be involved in the restoration and expansion of monastic foundations. He wanted Edgar's help to restore monasteries, since the king was considered a representative of Christ on Earth. He wanted Ælfthryth to become a supervisor of Benedictine nunneries.

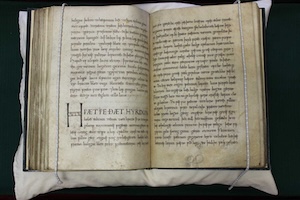

Æthelwold was nicknamed "father of monks" and "benevolent bishop" by others. Under his guidance, the monks of Winchester and elsewhere were better educated than the secular clergy. One modern scholar even claims that Æthelwold's vernacular writings were significant in the development of Standard Old English. [link]

Later, when Æthelred (the Unready) became king, Æthelwold was an advisor during the new king's minority. When Æthelwold died on 1 August 984, Æthelred wrote that the country had lost "one whose industry and pastoral care ministered not only to my interest but also to that of all the inhabitants of the country."

Twelve years after his death, a man claimed to have his blindness cured because he visited the tomb of Æthelwold, which started the process of his canonization. St. Æthelwold's feast day is 1 August.

I said a couple posts ago that I wanted to explore the two men who made St. Swithin famous. Æthelwold was one; the other was Dunstan. We'll explore his life and works tomorrow.