The 12th century saw a burgeoning of literature by figures whose names we actually know, like

Marie de France and Chrétien de Troyes (mentioned

here), Thomas of Britain and Hue de Rotelande. Then there were less clearly known names like Marcus, supposedly an itinerant Irish monk in the Regensburg, Germany, monastery called the Scots Monastery. The only item written by Marcus is the

Visio Tnugdali, the "Vision of Tnugdalus," found in five 15th century copies, one of which is Cotton Caligula A.ii, found in the famous

Cotton Library, that includes several other romances.

Written shortly after 1149, it is an account told to Marcus by a knight, Tnugdalus, called Tundale in English manuscripts. Marcus claims also to have translated the story from an Irish version. We are told that the story took place in Cork in 1148.

The story is of the wealthy Tnugdalus, who loved stealing, sex, and food and drink. He fought and gossiped and never did any good works. One day he goes to collect a debt owed to him. The borrower is unable to pay, and Tnugdalus flies into a rage. The borrower remains calm and talks Tnugdalus down, and invites him to a meal. While eating and drinking, however, Tnugdalus starts to feel ill, starting with his arm becoming paralyzed. When he tries to rise from the table, he collapses; he becomes cold as the proverbial stone, except for some slight warmth on his left side (where the heart is)?

This was on a Wednesday. The slight warmth leads those around him to keep him above ground. He regains consciousness on Saturday afternoon, upon which he has a story to tell.

He says his soul awakened in a dark place, and he wept, sure that his sins had caught up with him in the afterlife. A horde of foul and noisy creatures come rushing toward him, claiming that his sins confirmed his status as one of them! While he cowers before them, a point of light appears and grows closer, ultimately arriving and turning out to be his guardian angel, who asks him "What are you doing here?"

The angel tells him that he still has a chance to be saved. The horde freaks out about this, but the angel turns to Tnugdalus and says "Quick! Follow me!" The angel leads him through a dark tunnel, where the angel's light reveals the souls being tormented for different sins. This Dante-esque journey reveals more and more types of torment for different sins, some of which Tnugdalus experiences for a time, until the angel takes him on to the next experience. Ultimately, nearing the gates of hell, he sees Satan himself, a 150-foot tall human-shaped and thousand-armed creature chewing souls in his sharp teeth a thousand at a time.

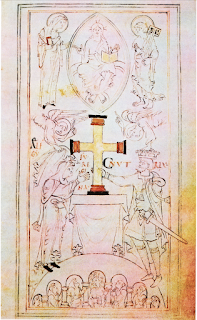

Purgatory is also on the itinerary's. great relief to Tnugdalus, who wants to stay there, but the angel assures him that even better awaits, and takes him to Heaven. They stand on a wall in Heaven—seen in the illustration above—and Tnugdalus now grasps knowledge of everything, and can see anything, no matter how far away. Suddenly,

... Saint Ruadan approached them. He welcomed Tundale happily, took him into his arms and hugged him.

‘My son, your arrival here is blessed indeed,’ he said, and they stood together. ‘From now onwards, while you live in the world you can look forward to a good end to your life. I was once your patron saint and in your worldly life you should be willing to show me some generosity and to kneel, as you well know, in my presence.’

St. Patrick is also seen, as well, as several historical deceased Irish bishops. Tnugdalus asks to stay, but is told that is not possible unless someone has led a good life. Tnugdalus must return to his body and change his ways if he wants to see this place again. Tnugdalus re-awakens in his body, astonishes all the people surrounding him by that and by the promise to amend his life.

The story is reminiscent of the Irish immram (Irish "voyage"), a hero's journey, usually by sea, through fantastical and legendary places. Marcus wrote in Latin, although he says he translated an Irish-language account. The story was translated into several languages, at least into French, German, and Norse. The Cotton version is Middle English. You can read a Modern English version here.

I'm curious about the place where Marcus wrote. What was a Scots Monastery doing in Germany? Tomorrow I'll tell you about the Schottenkirche.