After being released from confinement in Black Hall at Oxford, he wrote (in both Latin and English for wider awareness) De incarcerandis fedelibus ("On the Incarceration of the Faithful"). In it he declared that excommunication and incarceration were wrong, and those treated with such punishments should be allowed to appeal to the king.

The nobility and the mainstream population liked his reasoning, but the Church of course objected to the idea that the king could overrule their punishments. Pope Gregory XI, who had written against Wycliffe earlier, died before he could respond to this new essay.

Wycliffe then started speaking out even more strongly against the institution of the papacy and other Church practices than he had earlier. He argued before Parliament that those who sought sanctuary in churches could be forcibly removed. Excommunication, he believed, should require a trial before Parliament and a Synod. He repeated his contention that the Church should divest itself of wealth and property, that priests should be poor.

In 1381, he went too far (again) with his ideas about the Last Supper, rejecting the doctrine of transubstantiation. This was indeed a step too far, in that he lost the support of men like John of Gaunt, the young King Richard II's powerful uncle.

This happened in the summer of 1381, and from May to October the peasant uprisings collectively called the Peasants Revolt occurred. Wycliffe's teachings, spread about in English and emphasizing egalitarianism, certainly helped to fire up the countryside to rebel against the hierarchy that they recognized as oppressive. Wycliffe did not approve of the destruction caused by the Revolt, but he was often referenced by followers who took part. One of the most egregious acts during the Revolt was the killing of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon Sudbury.

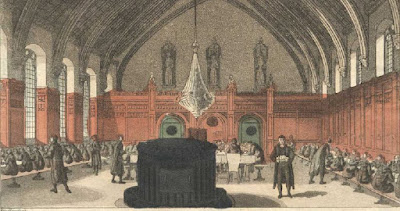

Sudbury was succeeded by William Courtenay, who had been Wycliffe's enemy for awhile. In 1382 Courtenay called an assembly in which he was going to deal with Wycliffe. This led to the interestingly named Earthquake Synod. Let me tell you how that went down (that's an earthquake joke) tomorrow.