The An t-Adhbhar Mòr (Scottish Gaelic, "The Great Cause"), a group of 104 men plus King Edward I of England, would hear all the claimants and determine who should ascend to the throne. This was modeled on the centumviri (Latin "hundred men"), the court of 105 used in Roman Law to settle questions of succession to property. They included 24 of Edward's council.

One of the points that needed to be decided by the Great Cause was the primacy of primogeniture (of which there were different interpretations) or customary law. Primogeniture could be male-preference or any first-born child. "Customary law" would split the parent's possessions among the children. The four chief claimants, who hired lawyers to speak on their behalf, were as follows:

- John Balliol, Lord of Galloway

- Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale

- John Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings

- Floris V, Count of Holland

Floris V's great-great-grandmother was Ada, a daughter of Henry, Earl of Huntingdon, who was son of King David I of Scotland. Floris claimed that when William the Lion was king, William's brother David had abandoned his right to the throne of Scotland by accepting the title of Earl of Huntingdon. This would invalidate the claims of the three other men listed above, who were all descended from Earl David. The problem was he had no proof, and assured the investigators that there must be records of this in Scotland itself if they would only search. At the orders of Edward I of England, they did search, and found nothing after several months to support his claim. Floris abandoned his claim in summer of 1292.

John Hastings was also descended from Ada, daughter of David, Earl of Huntingdon. He was an Englishman with a distinguished pedigree who in 1290 was summoned to Parliament and made a peer as Lord Hastings. His genealogical claim wasn't strong, so he took a legal approach. He argued that Scotland was not a proper kingdom, since it was only recently that its rulers were crowned and anointed. Therefore, there was no need to hand an intact kingdom over to a single person, and customary law allowed it to be split up among the heirs. The Great Cause did not take much deliberation to reject this idea and dismiss Hastings' claim.

Robert Bruce was the closest in blood to the now-defunct dynasty that started with David I. His lawyers also claimed that Alexander III (whose death started this whole difficulty) had named Bruce as his heir at a time when there seemed to be no other option. It's also worth pointing out that Bruce (as well as Balliol) had jumped at the chance to make a claim as soon as news of Margaret's death was known. Bruce argued against Floris's claim that the kingdom could be split, declaring that Scotland was indivisible and primogeniture should apply. Unfortunately for that claim, John of Balliol was descended from a child (Margaret) of David of Huntingdon who was older than the child (Isobel) from whom Bruce was descended. King Edward ruled that primogeniture through eldest surviving child pertained, and Bruce was dismissed. (Note: Edward had already established that England would be inherited by his eldest, a daughter, if he had no sons; absolute primogeniture, which means the sex of the child doesn't matter, was on his mind.)

Edward's determination of Bruce's claim happened in November 1292. Then there was a "November Surprise": Floris re-asserted his claim, and Bruce showed up to offer his public support of Floris! Floris decided to argue that the documents that would support him must have been stolen and his case should be reconsidered. As for Bruce, he did a 180° turn on the indivisibility of the kingdom. It seemed that he and Floris had probably made a deal: if Floris won, Bruce would be given a chunk of Scotland. Floris' claim was thrown out again for lack of evidence.

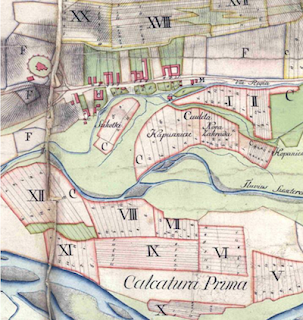

You can probably guess who became the next King of Scotland, and we will definitely present that case tomorrow, but today I leave you with an interesting footnote that explains the illustration.

The illustration above is of Pluscarden Abbey, currently a Catholic Benedictine monastery near Elgin, Moray. It was founded by Alexander II for the now-defunct Valliscaulian Order, which was absorbed by the Cistercians in the 18th century. In The Hague, Netherlands, there is a "certified" copy of a document that claims exactly what Floris claimed, signed and dated 1291 by the Bishop of Moray. It was supposedly found at Pluscarden Abbey. It is, of course, considered a forgery by all (I assume; there may be descendants of Floris V who have other thoughts).

See you soon.