Since we brought up Canterbury yesterday, and arguably its most famous archbishop, let us take a look at his predecessor, who was very much at odds with the King of England for the same reasons, but hasn't made it into as many history books.

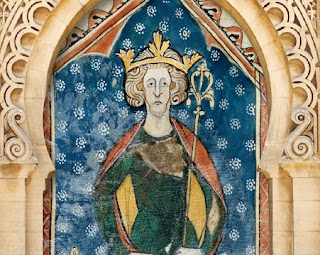

Theobald (c.1090-1161) was born in Normandy. He joined the abbey at Bec as a Benedictine and became its abbot in 1137. A year later, King Stephen of England appointed him the Archbishop of Canterbury. Theobald's relationship with the king was not ideal, especially when he clashed with the king's younger brother, Henry of Blois, who happened to be the Bishop of Winchester. Theobald was Henry's superior, but when your brother is the king, I suppose you tend to think you can get away with a little insubordination. Henry was appointed papal legate by Pope Celestine II, giving him some extra authority, but when Celestine died and Pope Innocent II (mentioned

here) took the throne of Peter, Henry lost his position. Innocent did not like King Stephen, and wanted to appoint Theobald as his legate. This required Theobald to travel to meet the pope, which King Stephen forbade. Theobald went anyway.

Which brings us to the major issue between Theobald and King Stephen—and it's the same issue that created the greatest difficulties between Thomas Becket and King Henry II: who makes the decisions, the leader of the country or the leader of the church? The Archbishop was appointed/approved by the king, but did that give the king authority over everything the archbishop did in the future?

(For more on Stephen of Blois and his attitude toward his own right to authority, see how he took the throne in during The Anarchy, Parts

One,

Two, and

Three, along with

this.)

One of Theobald's acts that exacerbated this conflict between temporal and spiritual authority was a synod Theobald called in 1151. It comprised mostly the bishops of the land, but the king and his son and heir, Eustace, were invited. The synod made eight new statutes, including ones forbidding taxing church property, or seizing church property, or prosecuting clergy in the royal courts as opposed to church courts.

An even worse slap in Stephen's face came a year later, when Stephen wanted to crown Eustace as his heir.* Theobald refused to participate, claiming that to crown Eustace and legitimize Stephen's dynasty would be perpetuating a crime. (See the four links above, describing how Stephen claimed the throne for himself.)

The civil war ("The Anarchy"; see above) that came not long after the death of Eustace on the White Ship tore England apart for years, until the Treaty of Wallingford. Ironically, the negotiations that brought peace between Stephen and Henry of Anjou (later King Henry II) were managed by Theobald and his long-time enemy, Henry of Blois. When Stephen died in October 1154, Theobald attended him on his deathbed; Stephen named Theobald regent until Henry could take up the reins of power. Although the two had feuded, there is evidence of mutual respect that allowed them ultimately to work together.

Theobald had the same relationship with Henry II, fighting over authority to try clergy in ecclesiastical courts rather than secular courts, and protecting church property from royal interference. Theobald helped his protégé, Thomas Becket, become chancellor. Becket seems to have become very close to the king, so close that the king was glad to make him Archbishop of Canterbury upon Theobald's death. That arrangement, however, if it was intended to make Henry's dealing with the church any easier than under Theobald, was surely a disappointment to the king. Becket proved to be as protective of the church and clergy as Theobald was. (But then, everyone knows how

that turned out.)

*

The Capetian Dynasty followed the practice of crowning the heir while his predecessor was still alive, previously posted about here.