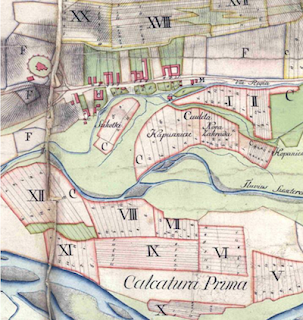

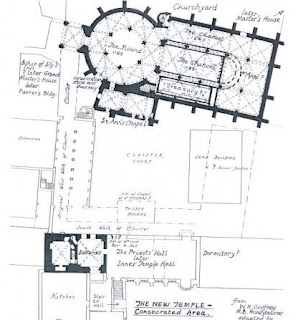

Edward had built Rhuddlan Castle in the north of Wales in 1277 after the first war between Edward and Wales. The Statute of Rhuddlan was issued from there, dividing the country into the the counties of Anglesey, Merionethshire, Caernarfonshire, and Flintshire, and revenues from them would now be collected by a new office, the Chamberlain of North Wales, who sent them to the Exchequer at Westminster. The English offices of sheriff and coroner and bailiff were established in each county.

Not everything about local law was changed, so there were differences when you crossed the border from England to Wales. Murder, larceny, and robbery were treated the same. The Laws of Hywel Dda used arbitration to settle disputes, not proclamations from a judge, and that system was maintained.

Inheritance laws were also different from England, where primogeniture was important to keep estates intact. When dealing with land, Wales followed partitive or partible inheritance, with property being divided among heirs. Some changes were made to align with England, however: if there were no son, a daughter could inherit; an illegitimate child could not inherit; widows were entitled to a third of their husband's estate.

The Statute of Rhuddlan was superseded by the Laws in Wales Acts of 1535/6 and 1542/3 under Henry VIII, or, more formally: An Act for Laws and Justice to be ministered in Wales in like Form as it is in this Realm and An Act for Certain Ordinances in the King's Majesty's Dominion and Principality of Wales. Henry wanted the law in Wales to match those of England exactly, and also desired to force English as the official language in a country that almost exclusively spoke Welsh. The 16th century is not really pertinent to this blog, however, so we won't go into any more of that.

Instead, let's ask why I indicated the Acts above as 1535/6 and 1542/3? Wasn't it clear what year they were established? It is, or was, but that depends on when you consider the year to start. Tomorrow let's talk about when the Middle Ages celebrated the "new" year.