16 March 2025

William of Tyre

14 December 2023

Prince John in Ireland

John may have had reason to be bitter from the start. His father had sought the pope's blessing to declare John King of Ireland, but Popes Alexander III followed by Lucius III were not in agreement, so John went as "Lord" instead of his hoped-for title "King." He arrived in Waterford with 300 knights and numerous soldiers and archers in April 1185, which of course caused anxiety among the Irish who saw an army rather than a diplomatic mission.

We have Gerald of Wales to thank for details*: his Topographia Hibernica tells how John was greeted by several Gaelic Irish leaders whose long beards made John and his men first laugh and then abuse the Irish by yanking their beards. On his tour through Ireland, he promised land grants to his retainers, further angering the locals.

His supposed goal of setting up administrative structures to maintain Anglo-Norman rule was a failure. He alienated the Irish, he ran out of money to pay his men (and lost some through desertion as well as in battles against Irish forces), and he had little or no skill as an administrator. His opposition in Ireland was not all Irish, either. Hugh de Lacey was an Anglo-Norman baron who had been made Lord of Meath by Henry years earlier. John complained to Henry that de Lacey prevented John from collecting tributes from the Irish leaders. This may well be true: Lacey had established a firm presence, and John's ham-handed approach to Ireland was disrupting a comfortable, pre-existing arrangement.

The Lord of Meath was not to remain a problem for John, however: he was killed a year later by an Irishman, Giolla Gan Mathiar Ó Maidhaigh. John was immediately sent back on hearing the news to take possession of de Lacey's lands.

It is unlikely that the Anglo-Norman plan to take over Ireland would ever be considered a positive event, but John's feckless attitude on his first tour certainly was not beneficial. Of course, there was already an Anglo-Norman presence (Hugh de Lacey, for example). In fact, there was already an Anglo-Norman "Lord" of Ireland, appointed by Henry years earlier but replaced by John at the Council of Oxford. His name was William FitzAldhelm, who was actually sitting at the Council of Oxford when Henry announced John's appointment to replace William. I'll tell you about him tomorrow.

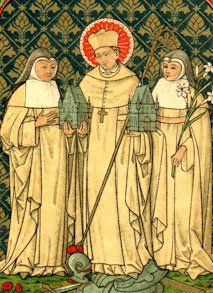

*The illustration is from a copy of the Topographia: it shows the killing of a white mare that is then made into a stew in which the new king bathes before his courtiers eat the stew. (I wouldn't make this up.)

01 November 2022

Geoffrey the Bastard

Geoffrey is assumed to be Henry's eldest son, born about 1152 (the same year Henry married Eleanor of Aquitaine and started having legitimate heirs). Geoffrey's mother is unknown. One chronicler hostile to Henry, Walter Map, says she was a whore name Ykenai. Other sources claim the mother was likely Rosamund, but there is no evidence for that.

Geoffrey was named Archdeacon of Lincoln by September 1171. This would have been a remarkable appointment for one so young: Gerald of Wales says he was barely 20 when he was made bishop in May 1173! He had come from land owned by a cathedral in the diocese of London, and a prebend, both of which generated income for him. Pope Alexander III objected to his appointment as bishop—it seems that he did not execute the duties of the positions he held previously—and Geoffrey traveled to Rome in October 1174 to meet with Alexander and receive a dispensation (he was very young, and had never been properly ordained a priest to our knowledge) so his appointment could be confirmed.

Note that, if you look at yesterday's post regarding the revolt by Henry's oldest legitimate son, Henry appointed Geoffrey bishop two months after three of his sons were rebelling against him, and Geoffrey's journey across the continent did not take place until the rebellion had been put down and it was safe for Geoffrey to travel through territory over which Henry had re-asserted control. In fact, the "loyalists in northern England [that] captured the Scottish forces" mentioned in that post were led by Geoffrey! Henry rewarded loyal service.

Henry's rewards to his son were only related to the church, however, which had a few results: it offered him financial support, it took him further away from ambitions of inheritance, and it precluded the desire to find him a suitable marriage.

Geoffrey, however, did not seem much inclined to remain in the religious life: he refused to be ordained, even though he remained in the position of bishop-elect. Ultimately, Pope Lucius III ordered Geoffrey to fish or cut bait: either be ordained and act properly like a bishop, or resign. Geoffrey chose resignation and became Henry's chancellor.

That was not the end of his religious life, however. After his father died—and Geoffrey was the only one of Henry's sons to be at his side when he died—the next king had plans for him. I'll go into that next.

29 October 2022

Thomas Becket, Aftermath

Henry's involvement—deliberate or not—in the murder tarnished his reputation; the death of Becket was one of the points brought against him during a rebellion in 1173. But let's focus on the immediate events after 29 December 1170.

The four knights responsible fled northward, to the castle of one of their number, Hugh de Moreville. Regardless of their "good intentions"—they thought they were carrying out orders of a king—the murder of an archbishop was not going to be without consequence. They might have thought to get to Scotland, where English law would not follow them. The four were excommunicated by Pope Alexander III. They were not in immediate danger of secular punishment: Henry did not confiscate their lands, which would have been appropriate for the circumstances. When they appealed to him for advice on their future in August 1171, however, he refused to help them. They ultimately went to Rome to seek forgiveness from the Pope, whose penance for them was to go to the Holy Land and support the Crusading efforts.

Back to Canterbury and 29 December 1170: the monks began to prepare the body for burial. Legend says they were astounded to find that he wore a hair shirt under his clothing: a sign of great piety, to willingly do penance through discomfort. His coffin was placed beneath the floor of the cathedral, with a hole in the stone floor where pilgrims could stick their heads in and kiss the tomb. The martyr's tomb became an enormously popular pilgrimage site; from martyr to saint took only two years: he was canonized by Alexander III on 21 February 1173.

Fifty years after his death, his bones were put into a shrine of gold and jewels—affordable because of the radical increase in donations and offerings due to the popularity of St. Thomas of Canterbury—and given a more prominent place behind the high altar. Sadly, the shrine and bones were destroyed by Henry VIII in 1538, and all mentions of Becket's name were to be eliminated. Despite Henry's efforts, Thomas Becket is still one of the most popular and best-known martyrs and saints in English history.

As was typical for prominent figures, especially saints, several legends cropped up about him with no evidence, but several locales tried to connect themselves to a now-famous figure. I'll share some of the more outrageous stories next.

28 October 2022

Thomas Becket, Martyr

One crisis point was averted when Pope Alexander III created a compromise that allowed Becket—in self-exile on the continent to avoid arrest for malfeasance—to return to England. Becket might have been more careful after that close call, but his awareness of the significance of his position as Archbishop of Canterbury guided his every move.

So when the king had his young son Henry crowned as his successor, the ceremony should have been performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, as was tradition. The elder Henry chose the secondary, the Archbishop of York, Roger de Pont L'Évêque, along with the Bishops of London and Salisbury, to elevate his son. Becket was insulted by this, and in November 1170 he excommunicated the three clergy involved.

...and here is where supposition takes over. King Henry, exasperated by the news, uttered words in what we would now call a "hot mic" situation. Exactly what he said, we don't know. A monk, Edward Grim, who says he was standing next to Becket during what happened next, reports Henry's words as "What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and brought up in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born cleric?" There are other accounts, including variations on the terse "Won't someone free me of this troublesome cleric?"

Four knights present took this as a command. Richard le Breton, Reginald FitzUrse, Hugh de Morville, and William de Tracy set out for Canterbury. On 29 December, they came to the cathedral, hiding their weapons and putting cloaks over their armor. Demanding that Becket come to the king in Winchester, his refusal made them retrieve their weapons and threaten him. They tried to drag him outside, but he held onto a pillar. With three sword blows to the head, Becket was finished.

This conclusion was only a prologue to more, and tomorrow I'll talk about what happened after.

05 July 2022

"Peter" Waldo

An anonymous chronicle of about 1218 (so not too long after the founding of the group c.1173, and only a few years after Waldo dies in 1205, so perhaps fairly accurate), gives more detail regarding the founding:

And during the same year, that is the 1173rd since Lord's Incarnation, there was at Lyons in France a certain citizen, Waldo by name, who had made himself much money by wicked usury. One Sunday, when he had joined a crowd which he saw gathered around a troubadour, he was smitten by his words and, taking him to his house, he took care to hear him at length. ... When morning had come the prudent citizen hurried to the schools of theology to seek counsel for his soul, and when he was taught many ways of going to God, he asked the master what way was more certain and more perfect than all others. The master answered him with this text: If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell all that thou hast," etc.

Then Waldo went to his wife and gave her the choice of keeping his personal property or his real estate, namely, he had in ponds, groves and fields, houses, rents, vineyards, mills, and fishing rights. She was much displeased at having to make this choice, but she kept the real estate. From his personal property he made restitution to those whom he had treated unjustly; a great part of it he gave to his little daughters, who, without their mother's knowledge he placed in the convent of Font Evrard; but the greatest of his money he spent for the poor. A very great famine was then oppressing France and Germany. The prudent citizen, Waldo, gave bread, with vegetables and meat to every one who came to him for three days in every week from Pentecost to the feast of St. Peter's bonds.

At the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, casting some money among the village poor, he cried, "No man can serve two masters, God and mammon." Then his fellow-citizens ran up, thinking he had lost his mind. But ... he said. "My fellow-citizens and friends, I am not insane, as you think, but I am avenging myself on my enemies, who made me a slave, so that I was always more careful of money than of God, and served the creature rather than the Creator. I know that many will blame me that I act thus openly. But I do it both on my own account and on yours; on my own, so that those who see me henceforth possessing any money may say that I am mad, and on yours, that you may learn to place hope in God and not in riches."

Other sources say the troubadour was singing a song about St. Alexius, who gave up his wealth to live in poverty like Jesus. Waldo puts is daughters into a convent, leaves his possessions to his wife, and began to travel Lombardy preaching the importance of poverty. He began to attract followers, and he and one of them traveled to Rome in 1179 to meet with Pope Alexander III. Waldo explained his primary beliefs: the value of voluntary poverty, the need for the Gospel to be in local languages, the belief in universal priesthood (that all men and women can preach the scriptures). Alexander approved the poverty, but not the preaching.

Waldo rejected the pope's declaration, and Waldensians continued to preach and grow followers, speaking out against other practices not found in the Bible: purgatory, indulgences, transubstantiation, prayers for the dead. They were persecuted for centuries for their beliefs—tortured, imprisoned, and killed—but they persevered to this day.

Who was this St. Alexius whose example inspired a successful merchant to make such a radical change? His story comes next.

07 January 2022

Clandestine Marriage

Peter Lombard (c.1096 - July 1160) was the Bishop of Paris and the author of Four Books of Sentences which became the standard theological textbooks for centuries. It was a compilation of sententiæ, authoritative statements on biblical passages. I'd like to talk about his conclusions on marriage.

Marriage customs varied among countries and cultures, and modern christian marriage requires an officiant (priest) and public statements about the intent to marry (banns) so that reasons why the marriage should not take place could be brought forth (such as a previous marriage, but yesterday's post made clear that more danico was not concerned about marriage being to only one person). Also, consummation was important, partially as a proof of the bride's prior status as a virgin.

Lombard had a different take on marriage, from his understanding of the Bible. Mary was married to Joseph, but she remained a virgin her entire life, rendering the need for consummation with a husband unnecessary. Pope Alexander III supported this notion.

Moreover, there was no priest to perform a ceremony in the Garden of Eden; it was sufficient for that marriage to take place in the sight of God. Therefore, what was the need for a priest? According to Lombard, the husband and wife need only profess their intent to marry. They could exchange the words "I take you as my husband" and "I take you as my wife" and their marriage ceremony was complete!

This was very liberating for young romantic couples (and older ones, I suppose), but this freedom was only to last for a couple generations. Innocent III would put a stop to it in 1215. Stay tuned.

31 January 2013

Monk Lord of the Manor

Gilbert came back to England in 1120 and, after being given the parishes of Sempringham and Tirington, joined the household of the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Bloet (who started as a clerk in the household of William the Conqueror and later became Chancellor).

He used his revenue from Tirington to aid the poor, and lived on the revenue from Sempringham. Robert Bloet's successor as Bishop of Lincoln ordained him a deacon, then as a priest after 1123, but when offered the archdeaconry of Lincoln he refused.

In 1130 his father died. Gilbert inherited his father's Lincolnshire manor and lands, and returned there. He did not, however, abandon the religious life. He now had the income to execute some grander plans. He decided to found his own monastic order.

The Gilbertines were originally composed of young men and women who had known and/or been taught by Gilbert in the parish school. It is the only monastic order founded in England. He used the Cistercians as his model, but when he appealed to the Cistercians themselves in later years for aid in maintaining and expanding the Gilbertines, he was rejected because of his inclusion of women.

Things turned sour for Gilbert in 1165, when he was imprisoned by King Henry II on the suspicion that he aided the fugitive Thomas Becket. He was eventually exonerated. Trouble found Gilbert again about 1180 when the lay brothers among the Gilbertines rose up because they were worked too hard (to enable the religious brothers to spend their days in prayer). The case was taken to Rome, but Pope Alexander III supported the 90-year-old Gilbert. Still, it is reported that living conditions for lay brothers improved afterward.

Gilbert, blind for the last few years of his life, resigned as head of the Gilbertines. He died in 1190 at the estimated age of 100+. His canonization did not take long: Pope Innocent III confirmed his sainthood in 1202, placing his Feast Day on 4 February, the day of his death, but it is now celebrated on 11 February.

19 January 2013

Prester John, Part 1

The 3rd century apocryphal text Acts of Thomas tells of St. Thomas and his attempts to convert India to Christianity. Although not included in the definitive collection of books of the Bible, it was still copied and read (Gregory of Tours made a copy), and sparked the imagination: what if there were a thriving community of Christians in exotic India, cut off from Europe and desirous of contact?

In the 12th century, a German chronicler and bishop called Otto of Friesling recorded that in 1144 he had met a bishop from Syria at the court of Pope Eugene III. Bishop Hugh's request for aid in fighting Saracens resulted in the Second Crusade. During the conversation, however, Bishop Hugh mentioned a Nestorian Christian (Nestorians and their origin were briefly mentioned here) who was a priest and a king, named Prester John, tried to help free Jerusalem from infidels, bringing help from further east. He had an emerald scepter, and was a descendant of one of the Three Magi who brought gifts at Jesus' birth.

The idea of Prester John, a fabulously wealthy and well-connected Christian potentate poised to help bridge the gap between West and East, captured the imagination. A letter purporting to be from Prester John appeared in 1165. The internal details of the letter suggest that the author knew the Acts of Thomas as well as the 3rd century Romance of Alexander.

The letter became enormously popular; almost a hundred copies still exist. It was copied and embellished and translated over and over. Modern analysis of the evolution of the letter and its vocabulary suggest an origin in Northern Italy, possibly by a Jewish author.

At the time, however, no analysis was needed for people to act. Pope Alexander III decided to write a letter to Prester John and sent it on 27 September 1177 via his physician, Philip. Philip was not heard from again, but that did not deter the belief in Prester John at all.

18 January 2013

Parochial School

This did not start in 1215, actually: the Third Lateran Council of 1179 (called by Pope Alexander III) had already declared that it was the duty of the Church to provide free education "in order that the poor, who cannot be assisted by their parents' means, may not be deprived of the opportunity of reading and proficiency."

One wonders how carefully churches complied with this. Because the school was integral to the church it was attached to, records are not as abundant as they might be if the school were a separate legal entity with its own building, property taxes, et cetera. We have to look for more anecdotal and incidental evidence.

Among Roger Bacon's unedited works is a reference about schools existing "in every city, castle and burg." John of Salisbury (c.1120-1180), English author and bishop, mentions going with other boys as a child to be taught by the parish priest. (Note that this is long before the Lateran Council decrees; it seems they may have simply affirmed and extended a long-held practice.)

Schools for young boys stayed attached to churches for a long time. A late-medieval anecdote of Southwell Minster in Nottinghamshire (pictured here; believed to be the alma mater of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury under Henry VIII) tells that a visiting clerk (priest) complained that the noise of the boys being schooled was so great that it disturbed the services taking place. And Shakespeare's Twelfth Night acknowledges these schools with the line "Like a pedant that/Keeps a school i' the Church." It would be a long time before schools for the young were deemed to need their own buildings.