Spies were sent into Poland, Hungary, and Austria for reconnaissance. Having planned their approach, three separate armies invaded Central Europe: into Hungary, Transylvania, and Poland. The column into Poland defeated Henry II the Pious.

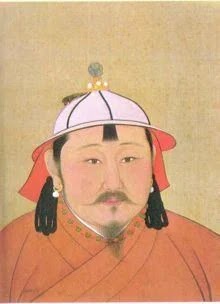

The second and third columns crossed the Carpathians and followed the Danube, combining with the Poland column and defeating the Hungarian army under King Béla IV of Hungary on 11 April 1241. They killed half the Hungarian population, then proceeded to German territory. Béla had sent to Pope Innocent IV for a Crusade against the Mongols, but the pope was focused on the Holy Land. (The illustration is from a 14th century history, the Chronicon Pictum, or "Illustrated Chronicle," and shows Béla fleeing.)

Austria, Dalmatia, and Moravia were occupied. While this was going on, a group led by Ögedei's son Güyük was conquering Transylvania.

Further advances in Germany were paused when the Great Khan died in 1241. Batu's thirst to continue was quenched by a reminder of Mongol law, that the chief descendants of Genghis had to return to Mongolia to elect his replacement.

Batu took his time returning, and the election was delayed for several years until Güyük was elected in 1246. Batu became the viceroy over the western empire. Batu returned to the western front and summoned the Grand prince of Vladimir, Yaroslav II. Batu put him in charge of all other Russian princes.

Around this time Batu came into contact with Europeans and their culture. Giovanni of Plano Carpini was sent by Pope Innocent IV to take a letter to Ögedei, protesting the Mongol invasion. Giovanni met with Batu, who gave him permission to continue to the court of the Great Khan. Giovanni described Batu as "kind enough to his own people, but he is greatly feared by them. He is, however, most cruel in fight; he is very shrewd and extremely crafty in warfare, for he has been waging war for a long time."

William of Rubruck also encountered Batu, describing him physically as about the same height as John de Beaumont (which tells those who never met John de Beaumont nothing useful, but other sources put him at 5'7"), and that his face was covered with red spots.

Others whose paths crossed with Batu are Queen Rusudan, who sent her son David to Batu for recognition. Sorghaghtani Beki sent Batu a warning to beware of a summons from Güyük. Before Batu reached Güyük, Güyük died mysteriously; Rubruck wrote it was one of Batu's brothers who did the deed.

The position of Great Khan was again available. What would Batu do about it? Come back tomorrow to find out.